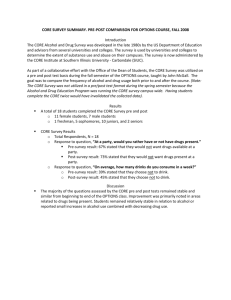

Noncompliance with Mandatory Disclosure Requirements: The

advertisement