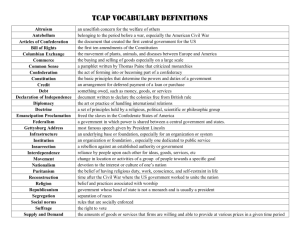

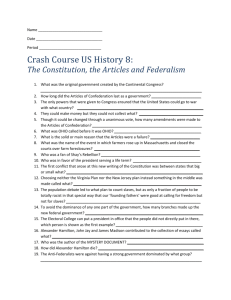

chapter nine: Articles of confederation and the constitution

advertisement