Looking Back on Gideon v. Wainwright

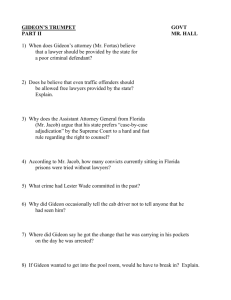

advertisement

Looking Back on Gideon v. Wainwright “Lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries.” By Peter W. Fenton and Michael B. Shapiro Photo: Library of Congress; NAACP mith Betts was indicted for robbery by the state of Maryland. An unemployed farmhand without funds to pay for an attorney, his request for counsel in a noncapital case was denied. He was a 43-year-old man of ordinary intelligence with one prior experience in criminal court. While the state’s case consisted of evidence identifying the accused as the robber, Betts claimed an alibi. Following a bench trial, he was found guilty and sentenced to eight years in The Scottsboro Boys prison. The case of Betts v. Brady1 seems simple enough, but its legacy spawned significant cases, including Gideon v. Wainwright,2 which is celebrating its 50th anniversary. Only 10 years before Betts, the Supreme Court began a 70-year process of applying the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of “the assistance of counsel” to the states in Powell v. Alabama,3 sometimes called the “Scottsboro Boys” case. Finding the right to access to counsel was fundamental due process, the Court held that in a state capital (death penalty) case, a defendant must be given access to counsel upon request. Previously the Court had refrained from requiring counsel in state criminal proceedings. Six years later, in 1938, the Court extended the right to “the assistance of counsel” to all federal criminal proceedings in Johnson v. Zerbst.4 Associate Justice Hugo Black, writing for the six-member majority (the decision was 6-2 with Associate Justice Benjamin Cardozo abstaining), stated: Since the Sixth Amendment constitutionally entitles one charged with crime to the assistance of counsel, compliance with this constitutional mandate is an essential jurisdictional prerequisite to a federal court’s authority to deprive an accused of his life or liberty. When this right is properly waived, the assistance of counsel is no longer a necessary element of the court’s jurisdiction to proceed to conviction and sentence. If the accused, however, is not represented by counsel and has not competently and intelligently waived his constitutional right, the Sixth Amendment stands as a jurisdictional bar to a valid conviction and sentence depriving him of his life or his liberty.5 24 Perspectives on Gideon at 50 THE CHAMPION The Supreme Court in 1963 “Lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries.”1 These words are at the heart of the opinion written by Justice Hugo Black in 1963 in the landmark case Gideon v. Wainwright.2 Expanding a precedent set by the Court in Powell v. Alabama3 in 1932, the Court in Gideon held that the Sixth Amendment’s right to legal representation was “fundamental and essential to fair trials,” thus entitling indigent felony defendants to court-appointed counsel in all American criminal cases. This unanimous decision was all the more remarkable in that it reversed the Court’s own contrary ruling in Betts v. Brady4 from just two decades before. Many factors may have contributed to the Court’s about-face, in such a relatively short period of time, on the critical issue of right to counsel. The 50th anniversary of Gideon is a most appropriate time to look back at the nine justices who spoke as one in this momentous case. The Court that decided Gideon included some of the most influential jurists of the 20th century as well as our entire history as a nation. What follows is a brief description of each of them. Arthur Goldberg — Justice Goldberg occupied the so-called “Jewish seat” on the Supreme Court for just three years, from 1962 to 1965,5 at which time he resigned to become the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. His legal specialty was labor; he is credited with overseeing the merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and was secretary of labor in the early Kennedy administration. Nominated by President Kennedy for the Supreme Court, Goldberg was considered to be the fifth “liberal” vote, rounding out the solid majority anchored by Chief Justice Earl Warren. Byron White — Another JFK appointee, Justice White had served on the Court for less than a year when the Gideon case was heard. Over time, he proved himself to be a solid conservative on a mostly liberal Court. However, prior to his appointment, White served as a deputy attorney general under Robert Kennedy at a time when the Department of Justice began in earnest to promote integration of public schools and facilities. John Harlan — An Eisenhower appointee, Justice Harlan was known for his belief in judicial restraint. He looked to the political processes inherent in our system of government, most notably the separation of powers and federalism, to lead the way in protecting individual liberties.6 Thus, Harlan was the predictable dissenter in many of the Warren Court’s decisions that today would be cited as examples of judicial activism. W W W. N A C D L . O R G e ction of th ing, colle ted States arris & Ew ni H U o: e ot th Ph Court of Supreme Potter Stewart — Another justice appointed to the Court by Dwight Eisenhower, Stewart’s moderate stance often placed him with the minority in the years of the Warren Court. He opposed the notion that a “doctrine of incorporation” was inherent in the Fourteenth Amendment, and thus did not believe that the Court had a right or obligation to make all the provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. Nevertheless, he was a staunch defender of First Amendment rights and sided with the majority in rulings that favored school desegregation. William Brennan — Justice Brennan occupied the Court’s “Catholic seat,” which had been vacant for the preceding seven years. He was appointed by President Eisenhower in 1956, but later Eisenhower revealed that he regretted his elevation of both Brennan and Chief Justice Earl Warren to the Court. Although steadfastly liberal, he was known for his persuasive powers and the ability and willingness to form ad hoc alliances in furtherance of garnering majority support. Thus, Brennan was a driving force behind the solid four-vote liberal bloc that shaped what will be forevermore known as the “Warren Court.” Brennan believed that the Constitution was a living document, subject to new interpretations and applications as American concepts of justice evolved. Earl Warren — Dwight Eisenhower appointed this Republican former governor of California as chief justice in 1953, an action that Eisenhower later described as “the biggest damned-fool mistake I ever made.”7 Over the next 16 years, Warren presided over a Court that issued many momentous decisions in the realm of civil liberties and constitutional rights, including the 1954 school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education and landmark 1960s criminal procedure cases such as Mapp v. Ohio, Miranda v. Arizona, and Terry v. Ohio. “The Warren Court” came to be a term associated with the Doctrine of Incorporation and a vast expansion of the protections afforded by the Bill of Rights. Vilified throughout his tenure by many conservative Americans, particularly in the South, Warren himself would ultimately observe, “Everything I did in my life that was worthwhile, I caught hell for.”8 JUNE 2012 25 Tom Clark — Clark was attorney general of the United States in the early years of the Truman administration; Truman appointed him to the Court when a vacancy occurred in 1949. Although considered a swing vote on many issues, Clark did side with the Warren Court majority on many cases involving civil rights. He was the author of the majority opinion in Mapp v. Ohio,9 in which the Court extended the Exclusionary Rule to actions of state and local governments. William O. Douglas — Justice Douglas was, throughout his tenure, one of the most outspoken and controversial members to ever serve on the Supreme Court. A former Yale law professor, he was elevated to the Court by Franklin Roosevelt in 1939. Douglas was only 40 when he was appointed, and served longer than any other Justice, more than 37 years. He was perhaps best known for his anti-establishment viewpoint and his absolutist interpretation of the Bill of Rights. Hugo Black — Franklin Roosevelt’s first Supreme Court appointee, Hugo Black would serve for 34 years, throughout the tumultuous civil rights era and all the years of the Warren Court. Always a populist and liberal, he nevertheless faced criticism for a brief stint in the 1920s as a member of an Alabama chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Like William O. Douglas, Black was an activist justice who believed that the Court’s role was to enforce the Constitution’s guarantees.10 He wrote the majority opinion in Johnson v. Zerbst,11 in which the Court held that all criminal defendants in federal prosecutions had a Sixth Amendment right to court-appointed counsel. Notes 1. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 344 (1963). 2. 372 U.S. 335. 3. Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932). 4. Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942). 5. Supreme Court Justices, Arthur Goldberg (1908-1990). Retrieved from http://www.michaelariens.com/ConLaw/ justices/goldberg.htm on March 2, 2012. 6. Supreme Court Justices, John Marshall Harlan, II (18991971). Retrieved from http://www.michaelariens.com/ConLaw/ justices/harlan2.htm on March 2, 2012. 7. PBS, The Supreme Court: The Court and Democracy. PBS, retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/ democracy/robes_warren.html on March 2, 2012. 8. ROBERT BYRNE, THE 2,548 BEST THINGS ANYBODY EVER SAID (2003). 9. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). 10. Hugo L. Black, The Oyez Project at ITT Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved from http://www.oyez.org/ justices/huto_l_black on May 9, 2012. 11. Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938). Photo: US Supreme Court Historical Society Perhaps Smith Betts was counting on the Court to extend the applicability of the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of counsel to the states in noncapital offenses, but in the midst of World War II that was unlikely. Instead, Betts is (mis)remembered as the case that “created” “special circumstances.” For 21 years, until it decided Gideon, the Court wrestled with which cases were so complex, which defendants were in such dire need, or which courts or prosecutors were failing to safeguard constitutional rights. Betts was a 6-3 decision, with Hugo Black authoring the dissent, in which Justices Douglas and Murphy joined. In that dissent, he set the stage for future cases, and ultimately for Justice Hugo Black the unanimous decision in Gideon. “Whether a man is innocent cannot be determined from a trial in which, as here, denial of counsel has made it impossible to conclude, with any satisfactory degree of certainty, that the defendant’s case was adequately presented. … Denial to the poor of the request for counsel in proceedings based on charges of serious crime has long been regarded as shocking to the ‘universal sense of justice’ throughout this country.”6 Barely 20 years after Smith Betts’ trial, on June 3, 1961, someone burglarized the Bay Harbor Poolroom.7 The police arrested Clarence Earl Gideon the same day and charged him with the felony of breaking and entering with intent to commit petit larceny. Gideon was tried on August 4, 1961, before the Honorable Robert L. McCrary Jr. Appearing without an attorney, Gideon sought the appointment of counsel: The Court: Why aren’t you ready? The Defendant: I have no Counsel. The Court: Why do you not have Counsel? Did you not know your case was set for trial today? The Defendant: Yes, sir, I knew that it was set for trial today. The Court: Why, then, did you not secure Counsel and be prepared to go to trial?8. . . 26 Perspectives on Gideon at 50 The Defendant: Your Honor … I request this Court to appoint Counsel to represent me in this trial. The Court: Mr. Gideon, I am sorry, but I cannot appoint Counsel to represent you in this case. Under the laws of the state of Florida, the only time the Court can appoint Counsel to represent a Defendant is when that person is charged with a capital offense. The Defendant: The United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by Counsel. The Court: Let the record show that the Defendant has asked the Court to appoint Counsel to represent him.9 Gideon was tried, without the benefit of counsel, convicted by the jury and sentenced to the maximum punishment, five years’ imprisonment. While at Raiford State Prison he submitted a handwritten Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus on the denial of counsel issue to the Supreme Court of Florida. Following that court’s rejection of the Petition, Gideon sought relief from the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court accepted Gideon’s THE CHAMPION Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, asking counsel to discuss whether the “Court’s holding in Betts v. Brady … [should] be reconsidered?”10 Abe Fortas was assigned to argue on Gideon’s behalf, while Bruce Jacob appeared for the state of Florida. Also appearing as amici were Lee Rankin of the American Civil Liberties Union, and George Mentz, assistant attorney general of Alabama.11 Additionally, a brief supporting the appointment of counsel, urging reversal, was filed by 22 state attorneys general, led by Walter Mondale (Minnesota) and Edward J. McCormack Jr. (Massachusetts).12 When the Court decided Gideon in 1963, only Black and Douglas remained from the Betts Court. In a unanimous decision written by Black,13 the Court overruled Betts v. Brady, holding that “Betts was ‘an anachronism when handed down,’ and … should now be overruled.” Black further stated: [A]ny person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth. … The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours.14 Any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth. … The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours. ruling inevitable.”18 “I believe that by 1963, a majority of the Supreme Court had come to the conclusion that the ‘special circumstances’ rule engendered endless litigation and should be supplanted by a clear-cut standard. … There were only about half a dozen19 outlier states at that point.”20 “Frankfurter and Harlan saw that totality of the circumstances just was not working even though there had been plenty of time for it to do so. … I think Gideon was inevitable.”21 Fortas realized that the “special circumstances” test was unworkable, and found a theme that tied it to the federalism issue: If you are concerned about issues of federalism … you then should oppose the special circumstances rule. Otherwise, federal court[s] would review what the state court did under [a] vague, special circumstances standard … [an] ad hoc and ex post facto review. … What could be more of an irritant to a state court judge than to have his judgments continuously reviewed under that kind of a standard?22 If overruling Betts was a foregone conclusion, then the issues that remained in Gideon were whether its application would be retroactive or prospective only,23 and ultimately how to pay for this extraordinary increase in the right to counsel.24 In recent correspondence with Bruce Jacob, he noted that there is still an issue with “the Was Gideon Inevitable? In the 21 years between Betts and Gideon, the Court wrestled with the right to counsel in state courts. While, to Justice Black, this was a right so fundamental to the concept of justice that it trumped any concession to federalism, other members of the Court, notably Frankfurter and Harlan, were not so easily convinced.15 Only one year before Gideon, Harlan finally conceded that “[t]wenty years’ experience in the state and federal courts with the Betts v. Brady rule has demonstrated its basic failure as a constitutional guide.”16 Then, only seven months before Gideon was decided, Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter stepped down from the Court.17 Finally, a review of the no-less-than 22 cases addressing the right to counsel between Betts and Gideon shows a steady progression towards overruling Betts, with fewer and fewer dissenting opinions. “The failure of Betts over many years to provide a workable standard for the provision of counsel made its overW W W. N A C D L . O R G JUNE 2012 27 practical and financial problems involved in implementing a change to an automatic rule providing counsel in every case, regardless of the circumstances.”25 [W]e were concerned about the prospect of turning a large number of inmates loose at one time. Florida could theoretically retry them, with counsel provided, but often witnesses are dead or unavailable, evidence has been misplaced, and retrials are not possible. We knew that the chances of winning the Gideon case were slim. Our main hopes were that the decision, if adverse to us, would not require appointment in misdemeanors, and that it would not be applied retroactively.26 How did the U.S. Supreme Court go from a 6-3 decision against requiring states to provide counsel to indigent defendants in Betts to a unanimous decision in favor of appointed counsel in state felony proceedings in Gideon? By 1963, none of the Betts majority was still on the Court, and two of the three dissenters — Black and Douglas — remained. They helped form the core of the “Warren Court” along with Chief Justice Earl Warren, William Brennan, and briefly, Arthur Goldberg. It has been suggested that Gideon, along with Mapp v. Ohio,27 and subsequent cases were all part of a civil rights paradigm shift stemming from Brown v. Board of Education.28 Finally, it is important to recognize that unanimity in Supreme Court decisions occurs in a minority of cases, and unanimity in reversing precedent is exceedingly rare. “About 30 percent of the Court’s orally argued decisions in the 19462009 period were decided unanimously,” but only 1.61 percent of those cases decided unanimously altered precedent.29 While Gideon established the legal framework for providing counsel at the state and local level, half a century later the practical implications of doing so remain. “The recent report by the Constitution Project, in Washington, D.C., makes it clear that society has not come close to fully implementing the requirements of Gideon, even 50 years later.”30 Notes 1. Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942). 2. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). 3. Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932). 4. Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938). 5. Id. at 467. 6. Betts, 316 U.S. at 476 (Black, J., dissenting). 7. Bruce R. Jacob, Memories of and Reflections About Gideon v. Wainwright, 33 STETSON L. REV. 181 (2003). 8. Trial Transcript at 8, Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). 9. Id. at 9. 10. 370 U.S. 908 (1962). 11. Only Alabama and North Carolina joined Florida in urging that Gideon’s conviction be affirmed. 12. The state of Oregon filed a separate brief. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963); Stephen B. Bright, Legal Representation for the Poor: Can Society Afford This Much Injustice?, 75 MO. L. REV. 683 (2010); Symposium, Gideon at 40: Facing the Crisis, Fulfilling the Promise, 41 AM. CRIM. L. REV. 135 (2004). 13. Justice Douglas wrote a concurring opinion. 14. Gideon, supra note 2, at 344. 15. Justices Frankfurter and Harlan were not supporters of the Doctrine of Incorporation, which addresses application of the Bill of Rights to actions by state and local governments. 16. Justice Harlan concurring in Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506 (1962). Note that Justices Frankfurter and White took no part in the decision. 17. Justice Frankfurter served on the Court from January 20, 1939, to August 28, 1962. 18. Anthony Lewis, author of Gideon’s Trumpet (1964), via email March 24, 2012. 19. In fact there were only five states that did not provide for counsel in felony cases in some form at the time of Gideon: Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Florida. 20. Abe Krash, associate counsel to Abe Fortas, who represented Clarence Earl Gideon before the U.S. Supreme Court, via email March 16, 2012. 28 Perspectives on Gideon at 50 21. Roger Newman, author of Hugo Black, A Biography (1994), via email March 4, 2012. 22. Symposium, supra note 12. 23. Burget v. Texas, 389 U.S. 109 (1967), applied Gideon retroactively. 24. Telephone interview with Walter Mondale, April 2, 2012. 25. Bruce R. Jacob, via email March 6, 2012. 26. Bruce R. Jacob, supra note 7. 27. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). 28. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); telephone interview with Walter Mondale, April 2, 2012. 29. Unanimous Decisions in the Supreme Court, Symposium on the Legacy of Justice Stephens, Northwestern University Law School, May 12, 2011. 30. Bruce R. Jacob, via email March 6, 2012. n About the Authors Peter W. Fenton, J.D., is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at Kennesaw State University. He is a former police officer, and has been teaching at the college level for 21 years. Peter W. Fenton Kennesaw State University 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144 678-797-2292 Fax 770-499-3423 E- MAIL pfenton@kennesaw.edu Michael B. Shapiro, J.D., is an Instructor of Criminal Justice and Business Law at Georgia Perimeter College. He is the former Executive Director of the Georgia Indigent Defense Council and a Past President of the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Michael B. Shapiro Georgia Perimeter College 555 N. Indian Creek Drive Clarkston, GA 30021 678-891-3291 Fax 678-891-3084 E- MAIL mshapiro@gpc.edu THE CHAMPION