Tentative title: WAL-MART SUPPLY CHAIN AND

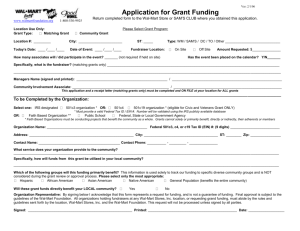

advertisement