IMPROVING NCLEX-RN PASS RATES

BY IMPLEMENTING A TESTING POLICY

JEAN SCHROEDER, PHD, RN

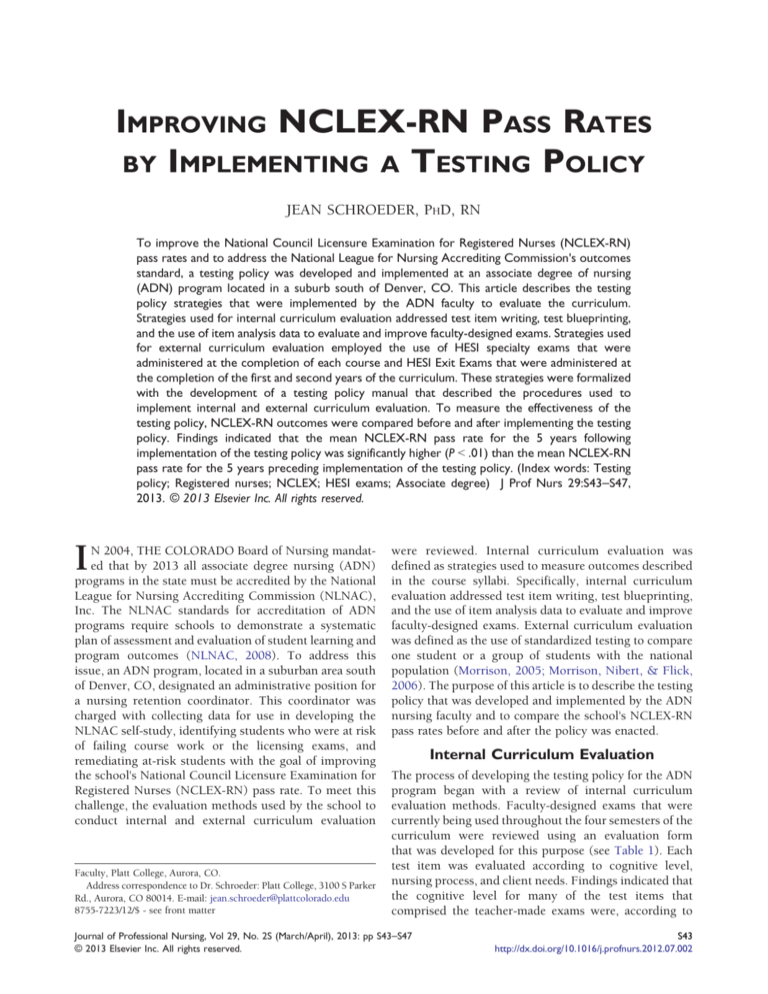

To improve the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN)

pass rates and to address the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission's outcomes

standard, a testing policy was developed and implemented at an associate degree of nursing

(ADN) program located in a suburb south of Denver, CO. This article describes the testing

policy strategies that were implemented by the ADN faculty to evaluate the curriculum.

Strategies used for internal curriculum evaluation addressed test item writing, test blueprinting,

and the use of item analysis data to evaluate and improve faculty-designed exams. Strategies used

for external curriculum evaluation employed the use of HESI specialty exams that were

administered at the completion of each course and HESI Exit Exams that were administered at

the completion of the first and second years of the curriculum. These strategies were formalized

with the development of a testing policy manual that described the procedures used to

implement internal and external curriculum evaluation. To measure the effectiveness of the

testing policy, NCLEX-RN outcomes were compared before and after implementing the testing

policy. Findings indicated that the mean NCLEX-RN pass rate for the 5 years following

implementation of the testing policy was significantly higher (P b .01) than the mean NCLEX-RN

pass rate for the 5 years preceding implementation of the testing policy. (Index words: Testing

policy; Registered nurses; NCLEX; HESI exams; Associate degree) J Prof Nurs 29:S43–S47,

2013. © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

I

N 2004, THE COLORADO Board of Nursing mandated that by 2013 all associate degree nursing (ADN)

programs in the state must be accredited by the National

League for Nursing Accrediting Commission (NLNAC),

Inc. The NLNAC standards for accreditation of ADN

programs require schools to demonstrate a systematic

plan of assessment and evaluation of student learning and

program outcomes (NLNAC, 2008). To address this

issue, an ADN program, located in a suburban area south

of Denver, CO, designated an administrative position for

a nursing retention coordinator. This coordinator was

charged with collecting data for use in developing the

NLNAC self-study, identifying students who were at risk

of failing course work or the licensing exams, and

remediating at-risk students with the goal of improving

the school's National Council Licensure Examination for

Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) pass rate. To meet this

challenge, the evaluation methods used by the school to

conduct internal and external curriculum evaluation

Faculty, Platt College, Aurora, CO.

Address correspondence to Dr. Schroeder: Platt College, 3100 S Parker

Rd., Aurora, CO 80014. E-mail: jean.schroeder@plattcolorado.edu

8755-7223/12/$ - see front matter

were reviewed. Internal curriculum evaluation was

defined as strategies used to measure outcomes described

in the course syllabi. Specifically, internal curriculum

evaluation addressed test item writing, test blueprinting,

and the use of item analysis data to evaluate and improve

faculty-designed exams. External curriculum evaluation

was defined as the use of standardized testing to compare

one student or a group of students with the national

population (Morrison, 2005; Morrison, Nibert, & Flick,

2006). The purpose of this article is to describe the testing

policy that was developed and implemented by the ADN

nursing faculty and to compare the school's NCLEX-RN

pass rates before and after the policy was enacted.

Internal Curriculum Evaluation

The process of developing the testing policy for the ADN

program began with a review of internal curriculum

evaluation methods. Faculty-designed exams that were

currently being used throughout the four semesters of the

curriculum were reviewed using an evaluation form

that was developed for this purpose (see Table 1). Each

test item was evaluated according to cognitive level,

nursing process, and client needs. Findings indicated that

the cognitive level for many of the test items that

comprised the teacher-made exams were, according to

Journal of Professional Nursing, Vol 29, No. 2S (March/April), 2013: pp S43–S47

© 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

S43

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.07.002

S44

JEAN SCHROEDER

Table 1. Exam Evaluation Form

Exam Evaluation Form

Knowledge

Cognitive level

Comprehension

Assessment

Planning

Nursing process

Implementation

Safe and effective care

Health promotion and

maintenance

Course objectives

Objective

Objective

Objective

Objective

Application

Analysis

1

2

3

4

Client needs

Psychosocial integrity

Evaluation

Physiological integrity

The exam's test items' numbers are inserted into one of each of the three categories so that each test item number appears in this form three times.

Bloom's taxonomy (Bloom, 1956), knowledge- or comprehension-level questions. Statistical exam analysis was

limited to measuring the difficulty level of each test item,

which was the percentage of students who answered a

question correctly.

To improve the course exams, the retention coordinator conducted a faculty workshop that focused on writing

critical thinking test items, designing a test blueprint, and

conducting a scientific exam analysis. Faculty were

introduced to the four criteria for critical thinking test

items: (a) contain rationales; (b) are written at the

application or above cognitive level; (c) require multilogical thinking to answer correctly; and (d) require a

high level of discrimination to choose the correct answer

from among plausible alternatives (Morrison et al.,

2006). Table 2 provides an explanation of each of these

four criteria. The opportunity to practice writing critical

thinking test items was provided at the workshop, and

the retention coordinator consulted with the teaching

groups to assist faculty with editing current test items and

writing new questions that met these four criteria.

Faculty were encouraged to upgrade a minimum of

seven questions—editing them so that they met the four

criteria for critical thinking test items—each time an

exam was administered. The goal was to have no more

than 10% knowledge-based test items on any exam.

Additionally, exams were leveled so that by the time

students took the exams for the final course in the

curriculum, most of the questions were at the application

or analysis level. Within 2 years after the retention

coordinator role was established, most of the test items

administered within the curriculum met the four criteria

for critical thinking test items.

Faculty were also introduced to test blueprinting

(DiBartolo & Seldomridge, 2005; Morton, 2008; Tarrant,

Knierim, Hayes, & Ware, 2006) during the workshop and

had the opportunity to review a test blueprint developed

by the retention coordinator. Using the exam evaluation

form, faculty identified the objectives that were to be

tested by the exam and categorized the test items that

would be included in the exam by cognitive level, nursing

process, and client needs. Using this blueprinting process,

faculty added and subtracted test items so that the exam

contained no more than 10% knowledge-based test items.

Table 2. Criteria for Writing Critical Thinking Test Items

Criteria for writing critical

thinking test items

Explanation

1. Contain rationales

Test item rationales explain why the answer is correct and why the other choices are

incorrect. Providing rationales not only allows testing to become a learning process but

also helps reduce student dissatisfaction with test items.

2. Written at the application or above

cognitive level

Test items require students to apply content and concepts to clinical situations. Test items

are not merely the regurgitation of facts, which requires only memorizing. Rather,

students should be required to synthesize facts and concepts to solve a clinical problem.

3. Require multilogical thinking to

answer correctly

Test items require knowledge and understanding of more than one fact or concept to

solve the clinical problem presented in the question.

4. Require a high level of discrimination

to choose the correct answer

Test items require problem solving and decision making to answer correctly because the

options provided are so closely related that a high level of discrimination is required to

select the correct answer from among the plausible alternatives.

Morrison et al., 2006.

IMPLEMENTING A TESTING POLICY

To improve the exam evaluation process, a test analysis

software program was purchased. The retention coordinator served as the testing software administrator and

taught faculty how to interpret the data provided by the

test analysis program, in particular, measures of reliability. The determination of an exam's reliability, or

consistency of test scores, was reported using the

Kuder–Richardson Formula 20 (KR20) calculation. This

reliability measure ranges from − 1 to + 1, and the closer

the KR20 is to + 1, the more reliable is the exam. A KR20

of 0.60 was established as the benchmark KR20 for

teacher-made exams. To be a reliable exam, the test items

included in the exam must be discriminating; meaning,

they must be able to discriminate between those who

know the content and those who do not know the

content. The point biserial coefficient (PBCC) is a

measure of test item discrimination, and it too ranges

from − 1 to + 1. A PBCC of 0.15 was established as the

benchmark PBCC for test items included in teacher-made

exams. These data were provided by the test analysis

software program, and they were used by faculty to

evaluate test items and to revise questions (Clifton &

Schriner, 2010; Morrison, 2005). The strategies used to

implement internal curriculum evaluation were part of

the systematic plan outlined in the policy and served as

an ongoing assessment of student learning.

External Curriculum Evaluation

As a measure of external curriculum evaluation, HESI

specialty exams were administered to students throughout

the curriculum. Data obtained from these exams compared this group of ADN students with the registered

nurse (RN) student population throughout the United

States. HESI exams simulate the NCLEX-RN in that they

contain critical thinking test items, students are not

allowed to return to previously answered questions, and

the test item formats are the same as those used in the

licensure exam: four-option multiple choice, multiple

response, fill in the blank, hot spot, chart/exhibit, and drag

and drop (National Council of State Boards of Nursing

[NCSBN], 2006; Wendt & Kenney, 2009). Table 3

provides an explanation of these test item formats. These

HESI exams helped familiarize students with the type of

test items and the test administration process used by the

NCSBN, thereby helping to prepare them for the licensing

exam. Numerous researchers have reported that exposure

to the NCLEX-type questions is related to NCLEX-RN

S45

success (Bonis, Taft, & Wendler, 2007; DiBartolo &

Seldomridge, 2005; Morton, 2008).

HESI specialty exams contain 55 test items, 5 of which are

pilot items and do not contribute to the student's score.

These exams were used for external curriculum evaluation,

and students who did not achieve the faculty-designated

benchmark score of 850 were required to remediate. The

HESI Exit Exam-PN (practical nurse) was administered to

students upon completion of their first year of the

curriculum. In Colorado, ADN students who are enrolled

in community college programs are allowed to take the PN

licensure exam after completion of the first year of the

curriculum, so the HESI Exit Exam-PN helped prepare

students for the PN licensing exam. The subject matter

scores obtained from this exam were used to identify

students' academic weaknesses and to evaluate the first year

of the ADN curriculum. The HESI Exit Exam-RN was

administered in the last semester of the curriculum, and the

subject matter scores provided by this exam were used to

identify student weaknesses so that they could remediate

prior to taking the NCLEX-RN, thereby helping to ensure

their first-time success on the licensing exam. The data

provided by this exam were also used to evaluate the

nursing curriculum. The HESI Exit Exam-PN was a 110item exam, 10 of which were pilot items, and the HESI Exit

Exam-RN was a 160-item exam, 10 of which were pilot

items. Like the HESI specialty exams, 850 was the facultydesignated benchmark score for both HESI Exit Exams.

Students who did not achieve this benchmark score were

required to complete a remediation program designed by

the retention coordinator.

Testing Policy Manual

To maintain congruent implementation of internal and

external curriculum evaluation strategies, a testing policy

manual was developed by the retention coordinator in

conjunction with the curriculum committee. Morrison

et al. (2006) described the need for such a manual, and the

guidelines these authors provided served as the foundation

for developing the testing policy manual for the ADN

program. Internal curriculum evaluation topics—such as

writing style protocols used for test item writing, test

blueprinting, and benchmark statistical parameters for

exam and test item analysis—were included in the manual.

External curriculum evaluation topics—such as when each

HESI exam should be administered throughout the

curriculum, the faculty-designated benchmark scores for

these exams, and the consequences associated with failure

Table 3. NCLEX-RN Test Item Formats

Test item format

Explanation

Four-option multiple choice

Multiple response

Fill in the blank

Hot spot

Chart/Exhibit

Drag and drop

Require selection of one response from four options provided.

Require selection of more than one response from the options provided.

Require typing in the answer. Usually used for calculation questions.

Require identification of an area on a picture or graphic.

Require reading of information presented in a chart or exhibit to answer the clinical problem presented.

Require ranking of options provided to answer the question presented.

NCSBN, 2006.

S46

JEAN SCHROEDER

to achieve these benchmark scores—were also included in

the manual. The testing policy manual was provided to all

nursing faculty and became a valuable resource for

ensuring that quality evaluation methods were consistently

implemented throughout the ADN program.

Methods

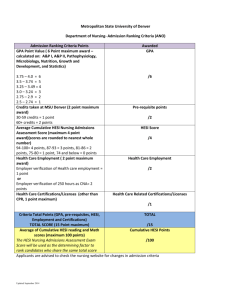

To test the effectiveness of the testing policy, NCLEX-RN

pass rates were compared for the 5 years prior to

implementing the policy and the 5 years after implementing the policy. A t test was used to compare mean

NCLEX-RN pass rates before and after implementing the

testing policy. The sample consisted of 572 graduates,

304 who graduated from the ADN program before

implementation of the testing policy and 268 who

graduated from the ADN program after implementation

of the testing policy.

Findings

Findings indicated that of the 304 students who took the

NCLEX-RN before implementation of the testing policy,

271 (89.14%) passed the NCLEX-RN on their first

attempt, and of the 268 who took the NCLEX-RN after

implementation of the testing policy, 260 (97.01%)

passed the NCLEX-RN on their first attempt. A t test

determined that the two mean NCLEX-RN pass rates

were significantly different (P ≤ .01). Table 4 describes

the NCLEX-RN pass rate for the ADN program for the 5

years before and the 5 years after the testing policy was

implemented. These findings indicate that a significantly

greater proportion of students passed the NCLEX-RN on

their first attempt after the testing policy was implemented than before the testing policy was implemented.

Discussion

Focusing on evaluation improves outcomes, which is one

reason why the NLNAC requires ADN programs to

demonstrate a systematic plan for evaluation of student

learning in their self-study for accreditation. Improving

evaluation by implementing consistent, curriculum-wide

strategies to measure internal and external curriculum

evaluation helped to improve the product produced by the

ADN program—ADN graduates. A significantly greater

proportion of graduates who enrolled in the ADN

program after the testing policy was implemented passed

the NCLEX-RN on their first attempt than those who

enrolled in the program before the testing policy was

implemented. However, fewer students completed the

ADN program after the testing policy was implemented,

11.84% less. This decrease in the number of graduates

could have been because of the more stringent testing

policy, and further studies on attrition and retention

should be conducted. Additionally, at the time this study

was conducted, applicants to the program were not

required to take an admission exam. Faculty noted that

students who entered the program with academic

weaknesses, such as poor reading and/or math skills,

were more likely to withdraw from the program than

those who had the academic background to succeed in the

ADN program. Therefore, in 2011, the faculty voted to

administer the HESI Admission Assessment to all

applicants and to study the usefulness of the data provided

by this exam in determining which applicants are most

likely to succeed in the ADN program.

To help prepare students for the ADN curriculum, all

students were required to attend a 3-hour test-taking skills

workshop during the first semester of the curriculum,

which was designed and implemented by the retention

coordinator. Additionally, HESI exams were administered

throughout the ADN curriculum as a measure external

curriculum evaluation, and students who scored lower

than 850 were required to remediate. This remediation

required students to review the HESI test items they

answered incorrectly and examine the electronic links to

textbook citations that are provided in the rationales for

questions answered incorrectly. These citations are stored

electronically in the students' individual online files and

can be accessed at any time for additional review. Students

were also required to answer NCLEX-RN practice test

items contained in review books and online review

products. Knowledge of content and concepts related to

nursing practice is essential, and these electronic links to

textbook citations and the NCLEX-RN practice test items

helped to reinforce such knowledge. However, to correctly

answer questions contained on HESI exams and the

NCLEX-RN and, in fact, to effectively practice nursing,

students and graduates must also be able to apply this

knowledge and these concepts to clinical situations. The

faculty believed that remediation that focused on the

application of knowledge and concepts to clinical problems

Table 4. Comparison of NCLEX-RN Pass Rates Before and After Implementation of Testing Policy

Before implementation of testing policy

After implementation of testing policy

Year

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

Total

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Total

Number

Number failed

% NCLEX-RN pass rate

45

5

89.8

43

4

90.7

76

8

89.5

70

7

90

70

9

87.1

304

33

64

5

92.2

42

2

95.2

49

0

100

56

0

100

57

1

98.8

268

8

Mean pass rate

SD pass rate

t

⁎ P b .01.

89.3

1.37

4.835 ⁎

97.2

3.38

IMPLEMENTING A TESTING POLICY

would be a better remediation resource for students

preparing for the licensure exam. Therefore, in 2011, the

faculty voted to implement the HESI online case studies as

an additional resource for student remediation. Further

study is needed to determine the effectiveness of these

remediation resources.

After developing the testing policy and establishing

benchmarks for exam analysis, the software program that

was used for exam analysis was discontinued. Consequently, the faculty members were required to calculate

test item difficulty levels and discrimination findings

without the benefit of a software program. The faculty is

currently investigating other software products that can

provide the same test analysis data, which is essential for

conducting a scientific exam analysis.

The HESI Exit Exam-RN was administered during the last

semester of the ADN curriculum, and students who scored

lower than the faculty-designated benchmark score of 850

were counseled to complete the remediation described and

encouraged to take an NCLEX-RN review course of their

choice. However, these students were not required to retest

with a parallel version of the HESI Exit Exam-RN, so the

effectiveness of their remediation could not be determined

until they took the licensing exam. Future studies might

examine the value of implementing a retesting policy for

those students who fail to achieve the faculty-designated

benchmark score on the HESI Exit Exam-RN.

Conclusions

The study school demonstrated a commitment to

improving outcomes by designating an administrative

position for a retention coordinator who, in conjunction

with the faculty, developed testing strategies that focused

on internal and external curriculum evaluation. These

strategies were formalized into a testing policy manual,

which was distributed to all faculty, and the strategies

described in this manual were implemented throughout

the curriculum. The internal and external curriculum

evaluation strategies that were part of the testing policy

fulfilled the NLNAC requirement for a systemic plan for

ongoing assessment of student learning and curriculum

evaluation. Internal curriculum evaluation strategies

focused on test item writing, test blueprinting, and

exam analysis as a means of improving curricular

S47

outcomes. External curriculum evaluation strategies

incorporated standardized HESI exams throughout the

curriculum that were used to identify students at risk of

failing the NCLEX-RN and to guide their remediation

efforts. The faculty determined that these testing policies

were effective as evidenced by achieving NLNAC

accreditation and significantly improving NCLEX-RN

pass rates.

References

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives:

Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: Longman.

Bonis, S., Taft, L., & Wendler, M. C. (2007). Strategies to

promote success on the NCLEX-RN: An evidence-based

approach using the ACE star model of knowledge transformation. Nursing Education Perspectives, 28, 82–87.

Clifton, S. L., & Schriner, C. L. (2010). Assessing the quality

of multiple-choice test items. Nurse Educator, 35, 12–16.

DiBartolo, M. C., & Seldomridge, L. A. (2005). A review of

intervention studies to promote NCLEX-RN success of

baccalaureate students. Nurse Educator, 30, 166–171.

Morrison, S. (2005). Improving NCLEX-RN pass rates

through internal and external curriculum evaluation. In M. H.

Oermann & K. T. Heinrich (Eds.). Annual review of nursing

education: Volume 3, 2005: Strategies for teaching, assessment,

and program planning (pp. 77–94). New York: Springer

Publishing Company.

Morrison, S., Nibert, A., & Flick, J. (2006). Critical thinking

and test item writing (2nd ed.). Houston, TX: Health Education

Systems, Inc.

Morton, A. M. (2008). Improving NCLEX scores with

structured learning assistance. Nurse Educator, 31, 163–165.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2006). Fast

facts about alternate item formats and the NCLEX exam.

Retrieved January 10, 2013, from https://www.ncsbn.org/pdfs/

01_08_04_Alt_Itm.pdf.

National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission, Inc.

(2008). NLNAC standards and criteria: Associate degree

programs in nursing. Retrieved January 10, 2013, from http://

www.nlnac.org/manuals/SC2008_ASSOCIATE.pdf.

Tarrant, M., Knierim, A., Hayes, S. K., & Ware, J. (2006). The

frequency of item writing flaws in multiple-choice questions

used in high stakes nursing assessments. Nurse Education

Today, 26, 662–671.

Wendt, A., & Kenney, L. E. (2009). Alternate item types:

Continuing the quest for authentic testing. Journal of Nursing

Education, 48, 150–156.