Sarah Gubbins, Inheritance and Innovation in Nerval's references to

advertisement

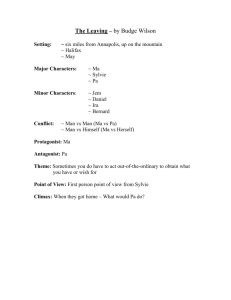

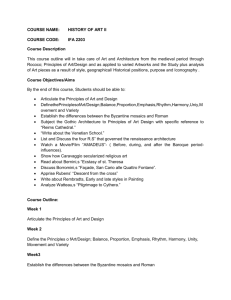

Inheritance and innovation in Nerval’s references to the visual arts SARAH GUBBINS Trinity College Dublin Nerval’s prose writings involve tensions between the exploitation of an existing literary and cultural heritage, and its transformation. This is evident in the poet’s fusion and subversion of conventional genres,1 in the blurred lines between plagiarism, recycling and the creative use of textual borrowings in his work (e.g. Voyage en Orient 1851; Jemmy 1854; Le Roman tragique 1844) and, as I will argue in this article, in his references to the visual arts. I will discuss the interplay between inheritance and innovation involved in the weaving of references to the visual arts into Nerval’s collection of nouvelles, or short stories, Les Filles du feu (1854), and into some of his travel writing including Lorely (1852) and Voyage en Orient (1851). During the mid-nineteenth century, when Nerval was writing, poetry in France was undergoing a transformation from the discursive or dramatic poetic language of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries into a condensed, metaphor-centred medium opening up new possibilities of expression and demanding new strategies of reading. It has been argued that many of the techniques used in the mid-century transformation of French poetic language were pictorial or spatial in nature (Scott 1988 and 2009, p.13). Poets were beginning to assimilate both images and forms from the visual arts into their work. Rather than using the natural world as a direct source of inspiration, they exploited images from the Salons and from L’Artiste, a journal which combined poetry, art criticism and engravings (ibid.). Further, they explored the pictorial and spatial potentialities of language through a new focus on metaphor and rhyme, the use of the sonnet form, and experimentation with line length. These techniques created a visual as well as an aural impact and many of them are exploited by Nerval in Les Chimères (1854), a collection of twelve sonnets. However, the influence of the visual arts is also discernible in his prose works. It is manifested in various ways, ranging from harnessing an inherited artistic tradition to conjure up vivid images to exploiting the ambiguities in the work of a painter such as Watteau in a way that challenges the conventions of representation in literature. 1 Drawing on an existing visual culture Unlike many nineteenth-century poets and writers (e.g. Gautier, Baudelaire, Fromentin, Zola, Laforgue and Mallarmé), Nerval did not engage in art criticism. However, through his involvement in the Impasse du Doyenné group, he had contact with painters such as Célestin Nanteuil, Narcisse Diaz, Camille Corot and Prosper Marilhat (Cassagne 1959, p.352). In an article on Nerval’s references to Italian art, Jacques Bony (2006, p.201) claims that Nerval is more interested in the subjects of paintings than in their form. Consonant with this claim is Hisashi Mizuno’s (2002) argument that Nerval uses visual artworks as points of cultural reference. By referring to them, he can immediately conjure up an atmosphere, character or scene and avoid unnecessary description: La traversée du lac avait été imaginée peut-être pour rappeler le Voyage à Cythère de Watteau. (Sylvie, p.545)2 [The lake crossing had perhaps been conceived to call to mind Watteau’s Voyage à Cythère.]3 Elle avait l’air de l’accordée de village de Greuze. (Sylvie, p.551) [She had an air of Greuze’s village betrothal.] Ne trouvez-vous pas qu’elle ressemble à la Judith de Caravaggio, qui est dans le Musée royal ? (Corilla, p.426) [Don’t you think that she resembles Caravaggio’s Judith, which is in the Royal Museum?] Je me refuse donc à toute description de la cathédrale : chacun en connaît les gravures. (Lorely, p.16) [I shall therefore avoid any description of the cathedral; everyone is familiar with the engravings.] Allusions to paintings and artists intensify the visual depiction of scenes and act as clues in the interpretation of events. Such references draw on an inherited visual culture that was assumed to be common to all educated readers. They occasionally evoke associations that foreshadow future developments. For example, Nerval hints at the dangerousness of the main female character in Corilla (p.426), by comparing her to Caravaggio’s Judith4 (see Figure One below); this prima donna eventually deceives both of her admirers: Fabbio – the leading male character – and his friend and rival, Marcelli. Nerval’s reference to the painting connotes a biblical story as well as the physical appearance of the woman in the painting. This reappropriation from the 2 visual arts of what was originally a textual subject was a common practice among nineteenth-century writers (Scott 1988 and 2009, p.13). Figure One: Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1652), Giuditta e Oloferne (1612-1613), Naples, Museo di Capodimonte. This painting was attributed to Caravaggio until the start of the twentieth century. Innovation: generical and narrative ambiguity My discussion of innovation in Nerval’s references to the visual arts will focus on his use of the paintings of Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). More than one hundred years before Nerval’s literary career began, Watteau was questioning the boundaries 3 of traditional genres in painting. He is known as the pioneer of the fête galante, a kind of painting in which a group of noble people indulge in flirtatious or amorous behaviour in a rural or park-like setting. By combining elements of landscape and history painting, Watteau was instrumental in the breaking down of the divisions between genres which were prevalent in European art from the seventeenth to the eighteenth century. His work is noted for its ambiguity. For instance, the identity of Watteau’s ‘shepherds’ is problematic. Are they upper-class revellers in rustic costumes? Peasants and members of the bourgeoisie invited to join in the festivities (Plax 2000, p.127)? Or are they simply studio models? Are the Harlequins and Pierrots who feature in Watteau’s paintings paid entertainers or nobles in disguise? Moreover, it is often difficult to tell whether the scenery in the background is intended to represent a real landscape or a painted back-drop (e.g. Les Charmes de la vie [The Delights of Life], c.1718, and Les Plaisirs du bal [The Pleasures of the Ball], 171517). In what follows, I will examine the ways in which Nerval exploits the subversiveness and the ambiguity of Watteau’s work in his own writing. Although Nerval refers to Watteau’s work in a general sense on several occasions, he only specifically mentions one painting: Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère (1717 [Pilgrimage on the Isle of Cythera], see Figure Two below). This painting is referred to in Voyage en Orient, when the narrator visits the island of Cythera and is disappointed to find it devoid of mythological festivities: Je cherchais les bergers et les bergères de Watteau, leurs navires ornés de guirlandes abordant des rives fleuries ; je rêvais ces folles bandes de pèlerins d’amour aux manteaux de satin changeant… je n’ai aperçu qu’un gentleman qui tirait aux bécasses et aux pigeons, et des soldats écossais blonds et rêveurs, cherchant peutêtre à l’horizon les brouillards de leur patrie. (Voyage en Orient, p.234)5 [I was looking for Watteau’s shepherds and shepherdesses, their ships, decorated with garlands, reaching shores covered in flowers; I was dreaming of those mad bands of love’s pilgrims in coats of shimmering satin... But all I saw was an English gentleman shooting at the woodcocks and the pigeons, and some Scottish soldiers, blond and dreamy, perhaps looking for the mists of their homeland on the horizon.] 4 Figure Two: Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère (1717), Paris, Musée du Louvre. This reference uses Watteau’s painting to emphasise the divergence between the narrator’s romantic expectations of the mythological island of Venus and the actual reality of the territory, which had recently passed from French to British control. However, just as it appears that the banality of Cythera has put an end to the sentimental musings provoked by Watteau’s painting, the sight of the Scottish soldiers sets the narrator off on another nostalgic reverie, as he projects onto them a longing for their home country. The failure of one mythological dimension does not deter him from exploiting the expressive potential of contemporary romanticism. This is an example of the seeming endlessness of association in Nerval’s writing. Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère is also central to chapter IV of Sylvie, one of Nerval’s most celebrated nouvelles, which forms part of the collection entitled Les Filles du feu [The Daughters of Fire]. Nerval describes a lake crossing, part of the fête de l’arc, a local festival, which may have been based on Watteau’s painting: ‘La traversée du lac avait été imaginée peut-être pour rappeler le Voyage à Cythère de Watteau’ (Sylvie, p.545). [‘The lake crossing had perhaps been conceived to call to mind Watteau’s Voyage à Cythère.’] Watteau submitted Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère as his reception piece to the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture [Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture] in 1717. Its original title was later crossed out by the Academy’s secretary and replaced with the words ‘une feste galante’. The implication of the original title is 5 that the painting’s subject is mythological. Its acceptance as such would have given Watteau the rank of history painter. However, it is likely that objections were raised concerning the fact that the painting has no source in ancient literature and that its subject was not an established theme in the genre of history painting (Posner 1984, p.192). It is also possible that the relatively small size of the painting disqualified it from being considered as a history painting. If we were to draw a line down the centre of the painting (just to the left of the dog on the hill) we would see that the right-hand side of the painting could almost be considered to belong to a genre painting. On the other hand, the presence of putti, a statue of Venus, and the classically nude rowers imply that the painting is not a simple genre scene. In changing the title of the painting, the academicians denied Watteau the privileges accorded to history painters, but they also acknowledged that his painting belonged to a new, modern genre (the fête galante). Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère epitomises the undecidability of Watteau’s work. James Elkins (1993) categorises it, along with da Vinci’s Last Supper, Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling, Botticelli’s Primavera, and Giorgione’s Tempesta, as a ‘monstrously ambiguous’ work. As is usual in Watteau’s fêtes galantes, the identity of the characters in the painting is debatable, and it is almost impossible to pin down with any certainty what is happening in the painting. Charles de Tolnay (1955) interpreted it as representing the different stages of romantic love. Moving from the statue of Venus towards the water, he argued that the couples embody persuasion, consent and harmony. The implication is that they will enter the ‘ship of Love’ and travel to Cythera, which symbolises fulfilment (Posner 1984, p.184). But, if the couples are on their way to Cythera, why is there no distinct land visible in the distance? Levey (1961) has argued that the figures in the painting are not leaving for Cythera but are about to return home from their pilgrimage. Claiming that the fact that the statue of Venus is covered with roses suggests a rite accomplished, he maintains that this interpretation would explain why a tone of sadness has often been detected in the painting. However, others have argued that while a journey to Cythera was a familiar image in Watteau’s lifetime, a return from Cythera had no precedent in either literature or art. They hold that if Watteau had wanted to drastically change the meaning of this established image, he would have done so more clearly; an indication 6 of a town or village on the other side of the water would have been enough to make the boat’s destination clear (Posner 1984, p.192). It could be argued that all of these attempts to decipher the meaning of Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère ultimately fail because of the painting’s narrative inconsistency; it does not bear analysis as a story but rather suggests a mood. To ask why we cannot decipher the island of Cythera in the distance, why Watteau did not paint a village on the other side of the water, or whether the work should be classified as history or genre painting is, to a certain extent, to miss the point; these ambiguities are central to the originality of the painting. The fact that Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère cannot be interpreted in a conventional manner makes it possible for the viewer to focus on the suggestiveness of the image; we do not need to understand the context of the scene to appreciate its dreamy atmosphere. What is interesting about Nerval’s reference to Watteau’s painting is that the generical ambiguity and narrative inconsistency of the painting are mirrored in Nerval’s short story. Sylvie is categorised as a nouvelle, but it involves strongly autobiographical elements; many of its features – the childhood spent in the Valois, the unrequited loves – correspond to what we know about Nerval’s life. It also contains eerie twists which are more often found in the conte (a folk or fairy tale): « Ah ! la bonne tante, dit Sylvie, elle m’avait prêté sa robe pour aller danser au carnaval à Dammartin, il y a de cela deux ans. L’année d’après, elle est morte ». (Sylvie, pp.559-560) [“Oh! My dear aunt...” said Sylvie, “She had lent me her dress to go dancing at the carnival at Dammartin two years ago. The year after that, she died.”] This description connotes a fairy-tale spell or curse. The banality of the events and the strange association that Sylvie makes between them contribute to the uncanny atmosphere evoked by this description. The mixing of genres, the association of elements that were previously thought to be contradictory, is one of the key features of modernity (e.g. Johnson 1979; Scott 2009). While the fusion of genres in Sylvie is less radical than in Watteau’s paintings – which combine elements of the previously separate categories of history, landscape, and genre painting – the inclusion of elements of autobiography and the conte in this nouvelle may indicate that, for Nerval, no one prose genre was sufficient for the full expression of experience. 7 Much of the undecidability of Sylvie results from the fluidity of Nerval’s representation of the narrator’s three love interests: Aurélie, a Parisian actress; Adrienne, a young girl from a noble Valois family with whom the narrator once danced as a child, who eventually joins a convent and dies; and Sylvie, a village girl with whom he was briefly romantically involved in his youth. The nouvelle traces the narrator’s various reunions with Sylvie, but is interspersed with his memories of or present-day encounters with all three women. Each woman seems to play different roles in Nerval’s universe: Aurélie, as an actress, is a professional role-player – changing parts every time she acts in a new play – and, according to the mores of the nineteenth century, a sexually available woman. In contrast, Adrienne is an aristocratic child and later a pure-spirited nun. The narrator equates them at one point: ‘Aimer une religieuse sous la forme d’une actrice !… et si c’était la même !’ (Sylvie, p.543). [‘To love a nun in the guise of an actress!... And what if they were the same?’] Although Aurélie and Adrienne have little in common in terms of social status, they are equally interesting to the narrator precisely because both of their lives involve transformation: ‘Cet esprit, c’était Adrienne transfigurée par son costume, comme elle l’était déjà par sa vocation’ (Sylvie, p.553). [‘This spirit was Adrienne transformed by her costume, as she already was by her vocation.’] Sylvie’s transformations are described in greater detail than those of Aurélie and Adrienne. Throughout the story, the narrator emphasises her modest origins: ‘Qui l’aurait épousée ? elle est si pauvre !’ (Sylvie, p.543). [‘Who would have married her? She is so poor!’] When she and the narrator dress up in old-fashioned wedding clothes, he compares her to ‘l’accordée de village de Greuze’ [‘Greuze’s village betrothal’] (Sylvie, p.551), which locates her squarely in a genre scene. However, as the nouvelle progresses, Sylvie becomes more difficult to categorise. She attempts to climb the social ladder, becoming a glove-maker (a promotion in terms of social status from her previous occupation as a lace-maker), taking singing lessons (‘Elle phrasait !’ [‘She used phrasing!’], Sylvie, p.560), and reading books recommended to her by the narrator, including Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloïse. This intertextual reference is appropriate since the narrator and Sylvie play roles similar to those of Saint-Preux and Julie (who, as the title suggests, resemble Abelard and Héloïse). However, it is also appropriate on a visual level, since it is the book’s illustrations by Moreau le Jeune which cause Sylvie to make the comparison: 8 Les gravures du livre présentaient aussi les amoureux sous de vieux costumes du temps passé, de sorte que pour moi vous étiez Saint-Preux, et je me retrouvais dans Julie. (Sylvie, p.555) [The book’s engravings also showed lovers in old-fashioned costumes so that, for me, you were Saint-Preux, and Julie reminded me of myself.] The fact that Sylvie does not grasp her similarity to Julie until it is presented in visual form indicates that she is far from integrated into Julie’s upper-class world. The most dramatic example of the plasticity of Nerval’s representation of Sylvie is his description of the lake crossing and the celebration which follows it in chapter IV. By comparing the event to Watteau’s Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère, Nerval introduces all the ambiguities of the painter’s work into the nouvelle. Just as the fête galante contains elements of history and genre painting, the lake crossing combines village participants with pursuits which were originally reserved for the nobility. Sylvie is portrayed as belonging to both worlds. She mocks the narrator for his Parisian ways: ‘Nous sommes des gens de village, et Paris est si au-dessus !’ (Sylvie, p.546) [‘We are village folk and Paris is so much more sophisticated.’] However, she is perceived by the narrator, due to her association with this noble celebration, as playing a more elevated social role than she did previously: Ce n’était plus cette petite fille de village que j’avais dédaignée pour une plus grande et plus faite aux grâces du monde. (Sylvie, p.546). [She was no longer the little village girl whom I had scorned for one who was taller and more socially adept.] Her heterogeneous identity fits well with the hybrid genre of the fête galante. Sylvie becomes more attractive to the narrator at this point because she has taken on another role; the range of expressive possibilities associated with her has increased. But the malleability of the identities of Sylvie and the other female characters in the nouvelle poses problems for the reader. The narrator states at one point: Tour à tour bleue et rose comme l’astre trompeur d’Aldébaran, c’était Adrienne ou Sylvie, – c’étaient les deux moitiés d’un seul amour. L’une était l’idéal sublime, l’autre la douce réalité. (Sylvie, p.567) [Now blue, now pink, like the deceptive star, Aldebaran, it was Adrienne or Sylvie, – they were two halves of a single love. One was the sublime ideal, the other, sweet reality.] 9 The fact that these characters can so easily be confused and merged sheds doubt on their autonomy. Indeed, the reader may wonder whether the narrator’s romantic interests are simply personifications of aspects of his fantasies. Like the viewer’s attempts to decipher the true meaning of Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère, the reader’s efforts to understand the essence of the characters in Sylvie are never fully adequate. Nerval’s reference to Watteau’s painting does not help to clarify Sylvie’s identity, but rather emphasises the fact that it is ambiguous. Faced with these uncertainties, the reader’s experience is transformed; the nouvelle’s generical and narrative undecidability accentuates its aesthetic qualities and prompts the reader to question the nature of representation in Nerval’s work. To conclude, Nerval does use references to the visual arts as a means of conjuring up an inherited culture, in order to intensify descriptions and as a point of departure for reverie. This may be understood in the context of a renewed interest in the use of the visual arts as a means of enriching literature in the nineteenth century (Scott 1988 and 2009, p.13). However, through his references to Watteau, Nerval is able to use the suggestive potential of Le Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère while, at the same time, exploiting its undecidability. In this way he combines inheritance and innovation. Although his reference to the painting succeeds in intensifying his description of the lake crossing by calling to mind an established image, the ambiguity of the image emphasises the malleability of representation in Sylvie, and confirms Nerval’s willingness to bend narrative conventions in order to achieve poetic effects. Thus, Nerval exploits not only the subject of Watteau’s painting, but also the formal aspects of its composition, using these to open up new possibilities of expression in literature, and perhaps to problematise the fixed status of literary forms and genres. Bibliography BONY, J., 2006. Nerval et la peinture italienne. In J. Bony, Aspects de Nerval. Paris: Eurédit. CASSAGNE, A., 1959. La Théorie de l’art pour l’art en France. Paris: Lucien Dorbon. ELKINS, J., 1993. On monstrously ambiguous paintings. History and Theory, Vol.32, No.3, pp.227-247. 10 DE TOLNAY, C., 1955. L'Embarquement pour Cythère de Watteau au Louvre. In Gazette des Beaux-Arts. Vol.4, pp.91-102. JOHNSON, B., 1979. Défigurations du langage poétique : la seconde révolution baudelairienne. Paris: Flammarion. LEVEY, M., 1961. The real theme of Watteau’s Embarkation for Cythera. The Burlington Magazine, Vol.103, No.698, pp.180-185. MIZUNO, H., 2002. Nerval, écrivain de la vie moderne, et la peinture flamande et hollandaise. Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France, Vol.102, pp.601-616. NERVAL, G. de. Œuvres complètes. Volumes One, Two and Three. Jean Guillaume and Claude Pichois (eds.). Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard, 1984, 1989 and 1993. PLAX, J., 2000. Watteau and the Cultural Politics of Eighteenth-Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. POSNER, D., 1984. Antoine Watteau. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. SCOTT, D., 2009. Generical Intersections in Nineteenth-Century French Painting and Literature: Manet’s La Musique aux Tuileries and Baudelaire’s Petits Poèmes en prose, in R. Langford (ed.) Textual Intersections: Literature, History and the Arts in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi. SCOTT, D., 1988 and 2009. Pictorialist Poetics: Poetry and the Visual Arts in Nineteenth-Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Notes: 1 For example, the boundaries between the nouvelle, the conte, theatre, travel writing, biography and autobiography are blurred. The prose narrative is interspersed with verse poems in La Bohême galante and in Petits châteaux de Bohême. 2 NERVAL, Gérard de. Œuvres complètes, volumes one, two and three. Jean Guillaume and Claude Pichois (eds.). Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard, 1984, 1989 and 1993. All quotes to Sylvie, Corilla and Lorely are taken from volume three. 3 All translations from the French are mine. 4 The painting referred to here, although attributed to Caravaggio at the time Nerval was writing, is actually the work of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1652). Nerval saw the painting in what was then the Real Museo Borbonico in Naples in 1834, as he indicates in a letter to Duseigneur, Gautier or Nanteuil (See Œuvres complètes, vol.1, p.1296). Caravaggio is the author of a different painting on the same theme, Giuditta che taglia la testa a Oloferne (1597-1600), which can be seen in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini in Rome. However, since this painting was assumed to have been lost until it was rediscovered in 1950, it is unlikely that 11 Nerval could have seen it during his time in Italy. See Bony (2006, pp.201-221) for a more detailed discussion of this issue. 5 NERVAL, Gérard de. Œuvres complètes, op. cit. All quotes to Voyage en Orient are taken from volume two. 12