Recovering the Creature: Storytelling and Existential Despair in

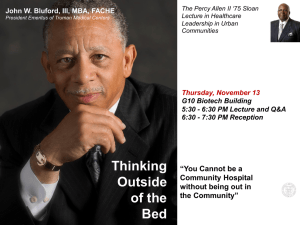

advertisement