English 110: Seminar in Academic Writing

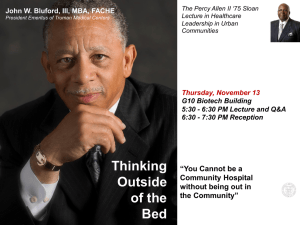

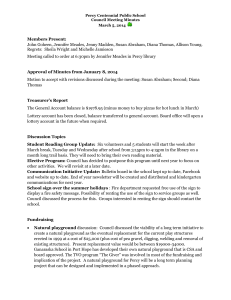

advertisement

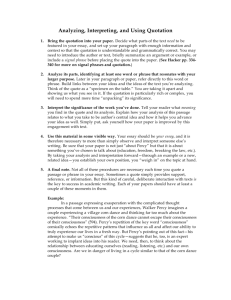

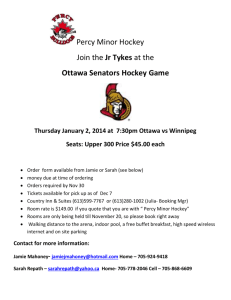

English 110: Seminar in Academic Writing Fall 2004 (T/Th) Scott Campbell Office: 222 Office Hours: 10-1 Tues. and by appt. E-mail: scott.campbell @uconn.edu COURSE INFORMATION B artholomae and Petrosky, eds., Ways of Reading (6th edition) Hacker, A Writer’s Reference (5th ed.) TEXTS GOALS • • • • • To help you see yourself as a writer and as someone who can use language to examine, develop, and communicate ideas. Through practice, trial, and revision, you will, I believe, become more confident about your writing. To help you discover, inhabit, and use the ideas of others (without, of course, plagiarizing those ideas). To emphasize the social aspect of writing. Writing is an act of communication, and I want you to anticipate your audience and see your writing in a context of others’ reading and writing. To show how writing leads to discoveries about your topic and about you. I want to break down the barrier you may see between personal and academic writing. All writing reflects the interests and perspective of the writer. To prepare you for further academic work. REQUIREMENTS You must complete several out-of-class essays (25-30 pages of revised writing). All papers must be typed using reasonable fonts, double-spacing, and standard one-inch margins. Typed rough drafts are required for all papers; a copy of each rough draft must be handed in to me. A rough draft is due even if you are unable to attend class. ALL papers must be handed in for you to pass the class. Late papers will be downgraded. In addition, required work for this course includes regular homework assignments and in-class writing. This is a seminar rather than a lecture course. Therefore, the success of this class depends on you as well as on me. Thoughtful discussion is an essential part of this class, and you will frequently work in groups of various sizes, which means you will need to be considerate of and attentive to others. It is your responsibility to keep up with the reading, to contribute to class discussions in the form of analytical comments or questions, and to attend class regularly and on time. See attendance policy below 2 First Day Writing Sample In “Imagination and Reality,” from the book, Art Objects, Jeanette Winterson has the following to say: Children who are born into a tired world as batteries of new energy are plugged into the system as soon as possible and gradually drained away. At the time when they become adult and conscious they are already depleted and prepared to accept a world of shadows. Those who have kept their spirit find it hard to nourish it and between the ages of twenty and thirty, many are successfully emptied of all resistance. I do not think it an exaggeration to say that most of the energy of most of the people is being diverted into a system which destroys them. Money is no antidote. If the imaginative life is to be renewed it needs its own coin. How well does Winterson’s statement reflect the world you’ve been living in? Using her description as your point of entry, write an essay that responds to her point (or to some aspect of it). Feel free to use your own examples and your own language. You do not have to agree with Winterson. Just try to present your own perspective on the topic and do the best you can in the time allotted. 3 Working With Texts: Walker Percy’s “Loss of the Creature” Choose a quote and examine it. Provide an “interpretation” of what Percy is saying. Take note of any terms from the quote that seem significant to you. Comment on at least one term and relate your “reading” (or interpretation) of the quote to the conversation we’ve been having about Percy and the world around us. An example can always help. 1.) A man in Boston decides to spend his vacation at the Grand Canyon. He visits his travel bureau, looks at the folder, signs up for a two-week tour. He and his family take the tour, see the Grand Canyon, and return to Boston. May we say that this man has seen the Grand Canyon? Possibly he has. But it is more likely that what he has done is the one sure way not to see the canyon. (588-589) 2.) Instead of looking at [the Grand Canyon], he photographs it. There is no confrontation at al l….He waives his right of seeing and knowing and records symbols for the next forty years. (589) 3.) It is true that they longed for their ethnologist friend, but it was for an entirely different reason. They wanted him, not to share their experience, but to certify their experience as genuine. (593) 4.) A poor man may envy the rich man, but the sightseer does not envy the expert. When a caste system becomes absolute, envy disappears. Yet the caste of layman-expert is not the fault of the expert. It is due altogether to the eager surrender of sovereignty by the layman so that he may take up the role not of the person but of the consumer. (594) 5.) It is only the hardiest and cleverest of students who can salvage the sonnet from this manytissued package. It is only the rarest student who knows that the sonnet must be salvaged from the package. (596) 6.) The pupil at Scarsdale High sees himself placed as a consumer receiving an experiencepackage; but the Falkland Islander exploring his dogfish is a person exercising the sovereign right of a person in his lordship and mastery of creation. (596) 7.) What is the best way to hear Beethoven: sitting in a proper silence around the Capehart or eavesdropping from the azalea bush? (598). 8.) I propose that English poetry and biology should be taught as usual, but that at irregular intervals, poetry students should find dogfishes on their desks and biology students should find Sh akespeare sonnets on their dissecting boards. (599) 9.) [The tourist] carves his initia ls as a last desperate measure to escape his ghostly role of consumer. He is saying in effect: I am not a ghost after all; I am a sovereign person. And he establishes title the only way remaining to him, by staking his claim over one square inch of wood or stone. (600) 4 Assignment #1 Text: Walker Percy, “The Loss of the Creature” Consider Percy’s idea of the “sovereign experience” and the examples he uses to explore it. Use one or two of Percy’s suggestions to develop your own example of a sovereign experience. Describe the obstacles that arise when one tries to have what Percy refers to as an “authentic” encounter. Are we ever free of the “packaging” that surrounds experience? Your goal with this essay should be to engage with Percy—to meet him on his terms and explore the consequences of his ideas. To do this you will need to quote the text and show how you are reading or interpreting these quotes. What terms or phrases does Percy use that seem valuable or useful to you? Are there places where Percy seems misleading or confused? How well does his description of the world fit your own personal experience? Think of your writing as a process of discovery, and use examples or ideas from both parts of Percy’s essay. Rough draft (onto page four) is due in class on Thursday, September 9th. Bring three copies. Final draft (onto page five) is due in class on Thursday, September 16th. Attach a copy of the rough draft. 5 Peer Review: Paper #1 Your name____________________ Writer's name_____________________ I expect that most papers can adequately grab a key term from Percy (such as "sovereignty" or "symbolic complex") and apply it to an example in a general way. But I'd like you to look carefully at the consequences of th is strategy. What does this paper accomplish by using Percy? Here are three things to consider. 1. Does the writer adequately contextualize Percy (the "frame" of this paper)? That is, does the paper explain what Percy means, defining terms, referring to examples from the text? In your review of this paper, write a response below that describes the paper's use of Percy and what might be done to strengthen that connection. Be specific. What words or phrases are "put to use" here? 2. How useful is the example (the "case") th at the writer has provided? Does the writer have an idea, an argument, that makes sense even without reference to the texts? That is, what is the paper about (and it should not be Percy)? W h at is the main idea or thesis at this point? Write th is out. Also, react to the example: is it a provocative one? Might it be strengthened in some way? What details seem most relevant? 3. What are the consequences of this idea or argument? In other words, what new territory does the argument reveal? Ask The Big SO WHAT? Question here. What are the goals of th is paper and are they met by the examples and points with in the essay? Why does the writer write what he/she writes? What new questions are raised by this essay? Use the back of this sheet if necessary. 6 Key Passages from Robert Coles’ “The Tradition: Fact and Fiction” The heart of the matter for someone doing documentary work is the pursuit of what James Agee called “human actuality”—rendering and representing for others what has been witnessed, heard, overheard, or sensed. Fact is “the quality of being actual,” hence Agee’s concern with actuality. (Coles 176) All documentation…is put together by a particular mind whose capacities, interests, values, conjectures, suppositions and presuppositions, whose memories, and, not least, whose talents will come to bear directly or indirectly on what is, finally presented to the world in the form of words, pictures, or even music or artifacts of one kind or another. (Coles 177) Events are filtered through a person’s awareness, itself not uninfluenced by a history of private experience, by all sorts of aspirations, frustrations, and yearnings, by those elusive, significant “moods” as they can affect and even sway what we deem of interest or importance, not to mention how we assemble what we have learned into something to present to others. (Coles 177) 7 The Waterbury Documentary Project Our goal here is to discover something about the “human actuality” of Waterbury, and we have to be sensitive to the complexity of this task. I will not tell you what you should be finding. Rather, I would like you to use your reading of Robert Coles’ essay as your inspiration for this “field trip.” Before you take any pictures, you should have an idea of what you are trying to do. Are you more like Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange or William Carlos Williams? What is your aim? Some guidelines: •Work with a partner. •You are responsible for yourself, so act responsibly. •Be respectful of the people and places you see. Do not intrude, confront, or disturb other people or situations. In fact, it’s appropriate to ask people for permission before you take photos of them. •You may take photos of buildings, vehicles, or other physical structures; you are not obligated to photograph people. You may find this much easier. •If you decide to, you could include yourself or your partner in the pictures. •Be creative. Experiment with ideas you have about how to best “document” your subject. •Have a plan or goal that is as clear as you can make it. •Do not stray into parts of the town you are unfamiliar with. You are not required to even leave the building. After all, our building (and the people in it) is a part of Waterbury. If at any point you feel uncomfortable or unsure, stop. •If you wish, you may “relocate” this experiment to another place such as the town where you live or another place you’re more familiar with. The photos we take are part of an experiment, and it is quite possible that your results (the pictures) will not be all you hope for. That’s okay. The real goal here is to feel what it is like to be a documentarian and to reflect on that process. 8 Waterbury Documents: Two Examples 9 Assignment #2: Images Choice #1 Texts: Robert Coles, “The Tradition: Fact and Fiction” Walker Percy, “The Loss of the Creature” The Waterbury photographs Robert Coles seems to recognize the difficulty of “documenting” a life. His essay uses several loosely connected examples to explore the complications that arise when one tries to represent, assess, or interpret someone else’s experience. And yet Coles seems to never doubt the value—you might even say need—for such documentaries. He suggests that his complex rendering of these issues is not just an academic matter and that it relates to “what happens every day when any two people talk to each other” (180). Walker Percy is even more emphatic about his wariness of “experts” who sometimes claim a kind of ownership over the things they know. But does Percy really think we do not learn from the commentaries and analyses of others? For this essay I would like you to move past “sovereignty” to consider the consequences of sharing experience. How does your reading of Coles contribute to your understanding of the issues involved in really knowing something (or someone)? Use your photographs of Waterbury as “evidence” of this attempt at knowing. Consider your image or images in light of what Percy and/or Coles argue. This essay will need to demonstrate your ability to put Percy, Coles, and your own ideas and work into a sustained conversation. It might be especially helpful to use Percy’s language to discuss Coles’s examples or vice versa. Do not attempt to be comprehensive or “complete.” Rather, choose moments in the texts which allow you focus on one main idea. Be creative about the connections you see between Coles and Percy. Rough draft (five pages) is due in class on Tuesday, October 5th. Bring four copies. Final draft (six pages) is due in class on Tuesday, October 12th. Attach a copy of the rough draft. 10 Assignment #2: Images Choice #2 Texts: Susan Bordo, “Hunger as Ideology” Robert Coles, “The Tradition: Fact and Fiction” or Walker Percy, “Loss of the Creature” An additional image In “Hunger as Ideology” Susan Bordo argues, “It is the created image that has the hold on our most vibrant, immediate sense of what is, of what matters, of what we must pursue for ourselves” (143). It’s a strong claim, and I’d like you to consider the consequences of her position as you define, too, your own understanding of what’s at stake. For this essay, you should illustrate a key connection between Bordo’s text and one other reading (Coles or Percy) and use this detailed discussion as a context for the examination of an image that you choose. Your image could be a published photo, an advertisement, a personal photo, or anything that you think makes an interesting “subject” for this essay. Your goal should be to show how the readings create a “lens” through which we may view this “created image.” What do the readings provide that may help us see this image in a different or new way? Remember that Bordo, Percy, and Coles do not agree in all ways. It may be useful to point to distinctions as well as connections. Rough draft (five pages) is due in class on Tuesday, October 5th. Bring four copies. Final draft (six pages) is due in class on Tuesday, October 12th. Attach a copy of the rough draft. 11 Analyzing, Interpreting, and Using Quotation 1. Bring the quotation into your paper. Decide what parts of the text need to be featured in your essay, and set up your paragraph wit h enough information and context so that the quotation is understandable and grammatically correct. You may need to introduce the author or text, briefly summarize an argument or example, or include a signal phrase before placing the quote into the paper. (See Hacker pp. 334-340 for more on signal phrases and quotation.) 2. Analyze its parts, identifying at least one word or phrase that resonates with your larger purpose. Later in your paragraph or paper, refer directly to this word or phrase. Build links between your ideas and the ideas of the text you’re analyzing. Think of the quote as a “specimen on the table.” You are taking it apart and showing us what you see in it. If the quotation is particularly rich or complex, you will need to spend more time “unpacking” its significance. 3. Interpret the significance of the work you’ve done. Tell your reader what meaning you find in the quote and its analysis. Explain how your analysis of this passage relates to what you take to be author’s central idea and how it helps you advance your idea as well. Simply put, ask yourself how your paper is improved by this engagement with text. 4. Use this material in some visible way. Your essay should be your essay, and it is therefore necessary to more than simply observe and interpret someone else’s writing. Be sure that your paper is not just “about Percy” but that it is about something you’ve chosen to talk about (education, freedom, breaking the law, etc.). By taking your analysis and interpretation forward—through an example or a new, related idea—you establish your own position, you “weigh in” on the topic at hand. 5. A final note. Not all of these procedures are necessary each time you quote a passage or phrase in your essay. Sometimes a quote simply provides support, reference, or information. But this kind of careful, deliberate interaction with texts is the key to success in academic writing. Each of your papers should have at least a couple of these moments in them. Example: In a passage expressing exasperation with the complicated thought processes that come between us and our experiences, Wa lker Percy imagines a couple experiencing a vill age corn dance and thinking far too much about the experience. “Their consciousness of the corn dance cannot escape their consciousness of their consciousness” (594). Percy’s repetition of the key word “consciousness” comically echoes the repetiti ve patterns that influence us all and affect our ability to truly experience our lives in a fresh way. But Percy’s pointing out of this fact—his attempt to make us “conscious” of th is cycle—suggests that he, too, is an expert working to implant ideas into his reader. We need, then, to think about the relationship between educating ourselves (reading, l istening, etc.) and our own consciousness. Are we in danger of living in a cycle similar to that of the corn dance couple? 12 Grammar Worksheet: Examples from Student Papers Instructions: Please examine each passage below and make corrections as needed. Some passages may not need corrections. Mark these passages as “okay.” 1. It may appear that the fork is to the left of the person sitting in front of the table, however it may look like the fork is to the right to the person on the other side of the table. 2. Now the problem with this is maybe the readers do not want to read something that the writer has cut or changed around to their individual standard, the reader may want raw facts and nothing more or less. 3. This photo was chosen because of how personal it was, how up close she was to the camera. Her face is bleak and hopeless; exactly what Lange is looking for to convey the message of the great depression. 4. Documentarians are individuals “who have discovered the balance between fiction and non fiction.” 5. In other words, anyone who takes their ideas and presents them to an audience can be considered a documentarian, even if they are as familiar as ones vacation. 6. Coles has the idea that everything should be presented to a consumer, to reveal the truth to them. 7. Much like the changes of then and now in how we like our music and the videos attributed to them, a picture of someone in the situation like “Ditched, Stalled, and Stranded” seems much like a depressing time to us, but to people who lived during that time, they could only hope they were as well off as the couple depicted in the photo. 8. Robert Cole’s quotes that our ideas of things will “bear directly or indirectly on what is, finally, presented to the world.” (pg. 177) 9. The image that I chose to represent this essay is a picture from a movie. 10. Susan Bordo argues that in many advertisements “women’s cravings” are depicted as “a dirty, shameful secret to be indulged in only when no one is looking” (165). Meaning that women have to hide their real desires. 13 Research Paper Checklist I. Presentation Do not forget to include the following: • a title (centered but not bold or underlined) • a staple • page numbers on all pages except the first • seven complete pages of writing (and no more than twelve) • page note citation for every quote (and name of author if needed) • a Works Cited page (in MLA format) at the end of the paper • four or more sources (including two of our course texts) • a copy of your Rough Draft • a separate bibliography of works related to the topic (in MLA form as well) II. Argument As you read and revise the body of your paper, think about whether your paper has the following elements: • an introduction that sets up the topic and prepares the reader for the moves you will make in the paper • a thesis that is apparent to the reader and developed or explored throughout the paper • moments of sustained analysis of quotes (in which you take a couple sentences and even perhaps a paragraph to interpret and explain a quote) • moments where you clearly explain how a text you are using impacts on your idea • an illustrating example (or “artifact”) • reasonable paragraph length (not more than 2/3 of a page) III. What not to do • plagiarize • write a report or a history • write extensive material that does not refer to or respond to sources • minimize your contact with scholarly sources (or the course texts) • use quotes without providing a context • turn in sloppy or mistake-laden work ***The Final Paper is due on Tuesday, December 14*** I have read this sheet and revised my work accordingly:___________________________ (your signature here) 14 Final Exam Essay From “I Stand Here Writing” by Nancy Sommers Please read the following passage by Nancy Sommers and the assignment directions and then spend approximately 10-15 minutes brainstorming and outlining your ideas. After you read it (and mark key words and sentences), write an essay which discusses the place of the personal in academic writing. Choose Sommers and one other text we have read this semester to examine what might be meant by “personal experience” and “academic,” or analytical writing. Try to focus somewhat on your own writing process in the class this semester to consider what new intersections you may now see between academic writing and personal experience. These essays we’ve read include those by Walker Percy, Susan Bordo, Robert Coles, Susan Griffin, and John Berger. If I could teach my students one lesson about writing it would be to see themselves as sources, as places from which ideas originate, to see themselves as Emerson’s transparent eyeball, all that they have read and experienced—the dictionaries of their lives—circulating through them. I want them to learn how sources thicken, complicate, enlarge writing, but I want them to know too how it is always the writer’s voice, vision, and argument that create the new source. I want my students to see that nothing reveals itself straight out, especially the sources all around them. But I know enough by now that this Emersonian ideal can’t be passed on in one lesson or even a semester of lessons. Many of the students who come to my classes have been trained to collect facts; they act as if their primary job is to accumulate enough authorities so that there is no doubt about the “truth” of their thesis. They most often disappear behind the weight and permanence of their borrowed words, moving their pens, mouthing the words of others, allowing sources to speak through them unquestioned, unexamined. At the outset, many of my students think that personal writing is writing about the death of their grandmother. Academic writing is reporting what Elisabeth KublerRoss has written about death and dying. Being personal, I want to show my students, does not mean being autobiographical. Being academic does not mean being remote, distant, imponderable. Being personal means bringing their judgments and interpretation to bear on what they read and write, learning that they never leave themselves behind even when they write academic essays. (Sommers 456) Keep in mind as you write that the writing goals of this essay include a central idea that makes and then later develops connections between two texts and also shows your own engagement with the ideas they present. You may also want to draw upon an example of how you used personal experience effectively as a text in an essay you wrote for this class. Allow ten minutes for proofreading to make sure that you correct any significant sentencelevel errors.