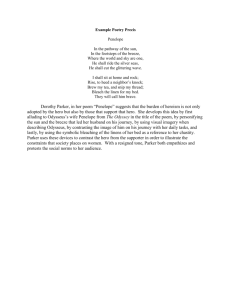

Strong myths never die. - Ghent University Library

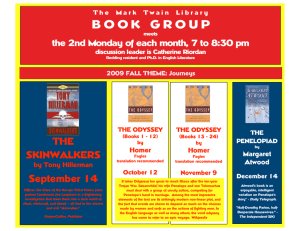

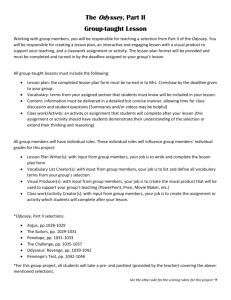

advertisement