CLARE JEREMY - University of Wales Trinity Saint David

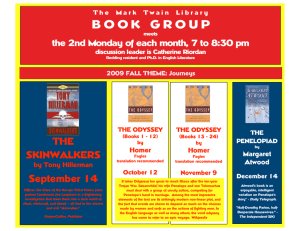

advertisement