The Odyssey - Guide to Great Books

advertisement

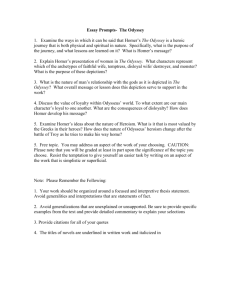

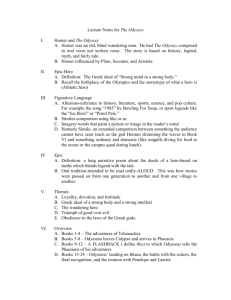

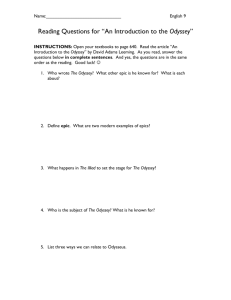

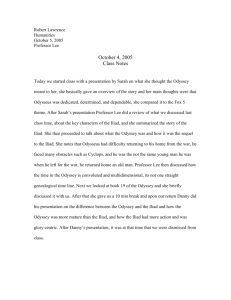

The Odyssey Yet, it is true, each day I long for home, long for the sight of home. If any god has marked me out again for shipwreck, my tough heart can undergo it. What hardship have I not long since endured at sea, in battle! Let the trial come! -Book V, 228–233 What makes it a “Great” Book? Unlike most sequels, the Odyssey is more of a contrast than a continuation of its predecessor, the Iliad. Some of the characters are the same, the history is place, but the war-torn beaches along the walls of Troy feel like a distant memory. The Iliad is about pure glory, regardless of the cost. The Odyssey is a classic tale about what matters most to one man and his family—home. In order to journey home, Odysseus must overcome countless obstacles and perilous trials on the high seas and among treacherous men. He is armed only with his wits and a stubborn hope that he will be reunited with his family. It is an inspirational story of incredible perseverance, danger, and love. Contents • • • • • • Presuppositions Historical Relevance Thematic Content Seminal Questions How to Approach Reading Assignments Presuppositions God: Complex Inner Struggles Between Gods and Men Fate plays a less prominent role in this story than in the Iliad. Man: A Cunning Creature Man is capable of outwitting the gods to accomplish at least some of his desires, but man is still vulnerable to their whims. The afflictions of the gods in this tale are sent either to test man’s resolve or punish him for his wickedness. Fate still is present, but man’s power to choose his end is greatly enhanced if he his resolve is firm. Founding Paradox: Fate and Freewill Coexist Everything is determined by fate, but humans are responsible for their individual decisions. Authority for Truth: Might Makes Right Individual will determines what is true. For both gods and men, for individuals and groups, whoever has the most power creates truth. The power to manipulate a situation comes in a variety of forms: physical prowess, beauty, rhetoric, supernatural fortunetelling, and so on. Virtue: Loyalty and Wisdom Loyalty is the standard by which we evaluate the moral character of each person in the Odyssey. Loyalty makes a person good, and a lack of loyalty makes him evil. Wisdom is the skill to accomplish good in the face of obstacles. Historical Relevance Background Like the Iliad before it, the Odyssey existed as an oral tradition, typically sung, with each telling varying from the one before it, until Homer wrote it down. Historians have nothing other than tradition to believe that Homer wrote it, but while many similarities between the two epics abound, it is impossible not to note remarkable differences between them, such as the tone in which the stories are told. The Odyssey seems much happier and less depressing than its counterpart. Another striking difference is the settings. One is set along the gruesome plains of war, while the other spans the high seas, mythical islands, and the domestic realm of home. Some historians believe that Homer composed this story in his later life, because it is more reflective of home and the simple life. About the Author Virtually nothing is known about Homer. Historians are not even sure if he even existed. Legend ascribes that a blind bard known as Homer wrote down his version of the oral tradition we know as the Odyssey sometime around the eighth century B.C. Impact on Literature The Odyssey is frequently referenced in later Greek works. It is regularly quoted by Plato and Aristotle. Homer’s epics greatly influenced the Roman poet Virgil’s masterpiece, the Aeneid. As the Western Church rose to power and Latin became the dominant language, Homer’s works lost some of their literary influence. They later made a significant comeback during the Renaissance with the sacking of Constantinople in 1453 A.D. Their stories and characters are regularly alluded to directly and indirectly through the present day. Thematic Content 1. Trials—This is a story about overcoming trials of all shapes and sizes. Some are quick and painful, some are long and agonizing, and others are seductively tempting. Only sheer cleverness and love of home and family enable Odysseus and his family members to overcome these obstacles. 2. Home—This is also a story about home and family. At the beginning of the story, each family member is, in his or her own way, in search of home. Individually, none of them experiences it. “Home” is only achieved when the family is united, and that does not happen until all family members have first overcome great trials on their own. 3. “Greek-ness”—Odysseus is the prototypical Greek: he is athletic, he is strong, but above all, he is cunning. Though the odds are always against him, he always gets the better end of the deal. He always wins the argument. He always adapts to the circumstances and uses them to his advantage. Wrestling, not archery or running, is his favorite sport. Wrestling is a physical game of chess, where its interlocutors are the pieces. It requires him to mix sweat and grapple with his opponent face to face. The Greeks love to outthink their opponents and overcome the odds by cunning. Examples of this include the Trojan Horse, the battle of Thermopylae (when 300 Spartans held 100,000 Persians in check along a narrow spit of land), and the battle of Salamis (when Athens lured the Persian Navy into a trap and its tiny force subdued the entire armada). 4. Coming of Age—Odysseus’ son, Telemakhos, has grown up without a father, and he must complete his journey to manhood before Odysseus can return. 5. Arete—Arete is the Greek word for “excellence” or “virtue.” In the Iliad, arete is mercilessness in combat and manipulation. In the Odyssey, arete is not yet associated with the Platonic or Judeo-Christian values of justice or righteousness, but is a much larger concept that includes cleverness, loyalty, and faithfulness. It is no longer only warriors who exhibit arete, but also youth, servants, women, swineherds, and even dogs. 6. Praxis—Praxis is the Greek word for “practical wisdom” or “cleverness,” and Odysseus and his family are no dummies. They possess this trait above all else, and it is no coincidence that Athena, the goddess of praxis, is Odysseus’ patron divinity. 7. Revenge and Reward—Revenge lurks throughout the book. Whether it is the Cyclops’ father, Poseidon, preventing Odysseus from getting home for gouging out the eye of his son, or Odysseus slaughtering the suitors who have fattened themselves off of his livestock, payback is coming. Rewards for faithfulness also abound. Just because the king is not home doesn’t mean he will linger forever, and he will reward those who are faithful in his absence, just as he will punish those who are wicked. Seminal Questions 1. What is home? 2. Do trials break us or make us stronger? 3. What does faithfulness look like? 4. How do we not lose hope in times of despair? 5. What are the virtuous or noble acts in the Odyssey? 6. Is Odysseus a hero? 7. What is the overall lesson of the Odyssey? How to Approach Different Translation: MCA uses Robert Fagles’ translation of the Iliad but Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of the Odyssey. There are some slight spelling differences between the two translators. Fitzgerald utilizes more transliterate phonetic spellings than Fagles. It takes some adjustment to get used to the change. This difference primarily shows up in names (Cyclops is now Kylops, Achilles is now Akhilleus, etc.). Multiple Plot Lines: There are several plot lines to follow. One is Telemakhos’ journey as he searches for his long-lost father. Another is Penelope’s patient waiting for her missing husband to return. The third is Odysseus’ own odyssey as he attempts to get back home to his wife and son. The epic jumps from one to the other quite suddenly, so it is important to pay attention to which plot you are following. Who is Speaking?: It is important to pay attention to who is speaking. Most editions do not have quotation marks setting aside one character’s comments from the rest of the material, and their speeches can literally go on for pages. Knowing who says what is half the effort in comprehending the story. Story Within a Story: Odysseus is not called the teller of tales for nothing. In addition to multiple side stories, he shares a four-book long account of his ten-year absence full of twists and turns. This passage contains most of what is generally thought of as the Odyssey. Odysseus’ narration is also is the only place in both the Iliad and Odyssey where magical creatures and monsters are seen—reader beware! Metaphors: Read the tales of Odysseus’ narration both at face value and as a metaphor. For example, Odysseus chooses to leave the isle of the beautiful Kalypso for the opportunity to return to his wife, Penelope. He is not interested in an empty physical beauty, but longs for a more satisfying relationship with his wife of great character. Each account is interesting in itself, but also has valuable lessons to teach. Emotional Imagination: Reading with empathy or emotional imagination not only makes the story more interesting, but also helps pick up the story’s rhythms. Line Numbers: Use the line numbers as a navigation tool to reference quotes and moments from the story. Reading Assignments Books I–VI Books VII–XII Books XIII–XVIII Books XIX–XXIV first Wednesday second Wednesday third Wednesday fourth Wednesday