Chapter 11 Writing about Fiction

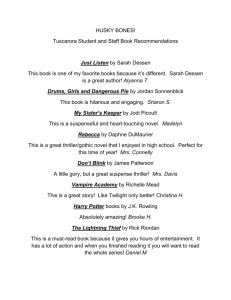

advertisement