19.1 Wrongful Termination by Employees

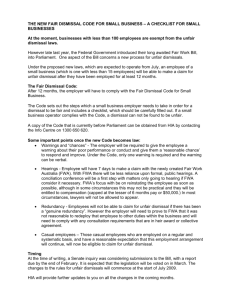

advertisement