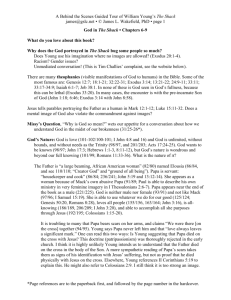

Meeting God at the Shack - This month: Unity of the Spirit Exploring

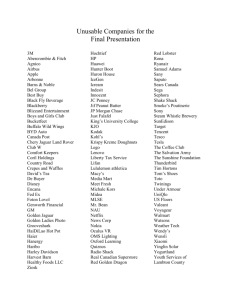

advertisement