NWP 5-01 Rev A -- Naval Operational Planning

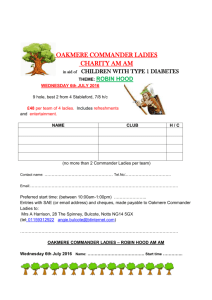

advertisement