- Lisztomania

advertisement

Akadémiai Kiadó

!"#$%&'#$()$!(*+',-.$,*$-"#$/0,11$2((3$()$4**5#1$6#$78'#9,*+:#

4;-"(9<1=>$7+;'$?#99,@3

/(;9@#>$/-;6,+$?;1,@('(:,@+$4@+6#A,+#$/@,#*-,+9;A$B;*:+9,@+#C$!D$EFC$G+1@D$HIJ$<KFFL=C$MMD$ENOP

ELE

7;Q',1"#6$Q.>$Akadémiai Kiadó

/-+Q'#$R%S>$http://www.jstor.org/stable/902543 .

4@@#11#6>$KTIUHIHUKK$KE>HN

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ak. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Akadémiai Kiadó is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studia Musicologica

Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.

http://www.jstor.org

The Role of Tonalityin the Swiss Book

of Annees de Pelerinage*

PaulMERRICK

Budapest

IntheLisztcentenary

year1986GyorgyKroopublishedanarticlelinwhich

he consideredthesignificanceof a remarkmadeby Lisztin a letterof 1835

referringto his "innerpath"(Ilgne interieure)as a composer.Againstthis

background

theauthortracedthegenesisofAlbumd 'unvoyageur[S (Searle)

156/R(Raabe)8, henceforthreferredto as SIbum], andits translormation

intoAnneesde Pelerinage.PremiereAnnee.Suisse [S160/R1Oa,hencettorth

referredto as Anneest. Ina bookon Liszt2publishedin 1987,I madethe

observationthatthe composerusedcertainkeys or tonalitiesin particular

contexts,givingtheexamplesof A7asthekeyof"love",andE asthekeyof

"religion",a conclusionreachedaiFter

studyingthe religiousworks, and

thosewitha programme.Later,in 1992, I wroteaboutDon Sanche3from

thisaspect,observingthatLiszt'suseofthesekeysintheearlyopera( 1825)

corresponded

to hisuseof theminhis matureworks,puttingthisforwardas

evidencethatLiszthimselfprobablycomposedthe musicratherthanhis

teachers,as hassometimesbeensuggested.To AW

andE I addedB, which

appearsonlyonceintheopera,asthemusicfora chorusandballetdepicting

the asylumof peaceandhappinesswhereloverslive for ever. Thiscorrespondsto Liszt's lateruse of thekeyin associationwithparadiseorheaven.

*TIlecontentsofthis articlewere presentedas a lecturein Finlandon 12June 1997, as partofthe Sulnlner

School tor postgl-aduate

doctoralstudentsorganizedby the SibeliusAcademyat Kallio-Kuninkala

In its presentform, it is dedicatedto the memoryof GyorgyKroo, who died on 12 November 1997

§ Kroo, Gyorgy 'La ligne interieure"- the Yearsof Transformation

andthe ' Albumd unv oyageur KStudia Mu.vicologicaAcademiaeScientiariumHus1garicae1986, pp 949 - 960

2 Merrick,Paul Revolutios1

as1dReligios1in the Musicof LisSt(Cambridge,1987) Keys are mentiolledintermittentlythroughoutthe book, butsee in palticulal pages 297-298

3 Merrick, Paul Origillalor Doubtful?Liszt's Use of Key in Supportof His Authorshipof Don Sanche

StudiuMusicologica 1992, pp 427X34

.il udia Musicologica

A cadeeniae

Ncie?liardtn l l un,¢uricae 3 9/'24. I 9'9h'>ll 3 6 7-3S'3

0039-3266/97:S

5.00 (¢ 1998 .4kademiai lsia(lo. Budapes

PazzlMer7Xick

368

In the followingdiscussionof the tonalitiesin AnneesI, I shallmakeuse

thereforeof the samethreeassumptions,namely:1. A7is associatedwith

love 2. E is associatedwith religion3. B is associatedwithheaven.This

use of key (amountingto key symbolism)is frequentin

"programmatic"

workswrittenatWeimar,whichis whenLisztproducedthef1nal''version"

I, andwithdrewtheearlierversion.4

of Albumi.e. A8nnees

his set of pieces?Arethe

Onwhatbasisdidthecomposerre-constitute

ninepiecespublishedin 1855a suiteor a cycle?Is thereanyinnercohesion

to the orderin whichthey appear(thereis no thematiccross-reference)?

of the

playedby tonalityin thef1nalorganization

What,if any,wasthe1^ole

set?Thekeysof theninepiecesof Liszt'sSnneesIare:

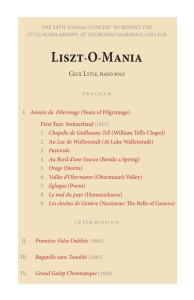

de G2zillaumeTell

1. C.hclpelle

tadt

2. All Iczcde Wczllens

3. Pastorale

4. A1lbordd 'ne sotlrce

5. Orage

6. Vcllleed'Oberngann

7. Eglogue

8. Le mal dzfpays

9. Lezclochezde Geneve

C

A ID

E

A;

c

e/E

A;

e

B.

waspublishedearThecyclewaspublishedinthisformin 1855.Albun1

lierin 1842,andsix piecesfromit wereincludedin the 1855set, thethree

new piecesbeingOrage,EglogueandLe maldupays. Thedatingof these

new pieces has been a subjectof dispute,5for examplein manysources

Eglogueisdatedfromthe1830s;accordingtoKroo,however,thereisno

in the 1855cycle, in whichcase its

traceof thispiecebeforeits appearance

composition,alongwithOrage,probablystemsfromthe Weimarperiod.

the 1855setfromthatof 1842is thetoOneof thefeaturesthatdistinguishes

nal sequencein whichthe pieces appear:Liszt changedthe orderof the

piecespublishedin 1842.He alsoin somecaseschangedthemusicitself,for

examplethe1842versionof Lesclochescontainsa longsectioninAb omitted

4 'Liszt regardedthis revision [i.e. Anslees 11as being synonymouswith the invalidation,or withdrawal,

of the earlierseries [i.e. Albllm]. And so thattherewould be no possibilityof performingor spreadingthe woIk,

Liszt bought back the publicationrights and the plates of the Albun1 d un lvovageur *om the work s publisher

Haslinger,in l 850. Nor did he permitthe cycle to be includedin the catalogueof his works. ' Fromthe Prefaceto

theNel1^Liszt Edition Series I volume 6, p. X.

S See Kroo, Gyorgy:Annees de PeleESinclge- Peemiere Annee: VersionsandVal iants.Sluclia Mllsicologiccr

1992, pp. 405-426.

Studic7 MvsiL01{7gicvl .4cadelo2iac SLienlic7ral*J11szr1,ffaricae39. /99d'

7tif

'

.?

*

*

Itristanue7atc

TheRole of Tonalityin the S 1pi^^

Book of Anneezde Pelerinczge

369

in 1855. Inonecase,Pastorale,hetooka piecepublishedin c. 1840vith the

titleFete villageois(andalso includedwithoutanytitleas No. 3 of Fleurs

melodiques,the secondpartof SIbum),andchangedthe key fromG to E.

Theearlyversionof Vallete

d 'Obermann,

by contrast,is inthesamekeyof e

minor/Emajoras thelaterversion,butis so differentthatit constitutesvirtuallyanotherpiece.6Obviouslya complicatedprocessof re-arrangement

andreE1nement

wasgoingon in Liszt'smind.

Oneof themosttellingprocessesof changeis thatcontainedin Le mal

dupays. The 1855versionusesa songfirstgivenby Lisztas a quotationin a

piece publishedin 1836, Fantaisieromantique

sur deuxmelodiessllisses

(S157, R9.) The song is not by Liszt, butwas publishedin 1818, entitled

Hemehlied (songof homesickness).

7 Liszt's treatment

of it in 1855, houever,diflaered

musicallyfromthatof 1836(MusicexampleA). ThissongapDewsHeins ch. _ Lollg;l!7for if orne.

Ln NOStAlgie. tL1 dU paos._ Bonragy.

molto yrosllzziuto 1s znelodta

-

co

l(zoz

Jre

ItilltsJelido

--

t

i!

les

5* e =

ctcco7ztpaqnenaenfs

gti accon*,lJayflelzlc{;

S 4 $

to7<otls

p

S

S

$ It

a

tS5<;

r

z

F

r

?

t

4

_9°

*

r

,viarto

sein,vre ,vianc

Music exampleA (i): Fantaisie romantiquesur dez{xmelodiessuisses, bars 136-15 1

6 See Kleinel-tz. Rainel-: Zul) Pl oblem des Frullwerks' bei Fl anz Liszt aln Beispiel xzon"Vallee d Obel-mann", StudiaMasicologica, 1992, pp. 251 -26S .

7 See Kroo, Annees/Versions, StadiaMusicolo,gica1992, p. 41 S.

iSttzclint.1lit.sicsZo,gicLt.4c LtJelrtinteiSKicol?tiLtl

,,

Ht,t7ga,-ic,v 3 9. / 99,S'

-S,

D

-

7()

?SjS

|9-rv

Wt

j

c>;)rcssiso

+'''S-1

-HS*

s,

<¢.;1,

--s

->

/

j

!---. -r- -.-4; _-ssg;XeLf-H-s-,

M - - 1- - 19.v>

-

'

FA==

il%s:li

,_

-O

= e-

z

j

Pazll Merrick

370

.fl\ltt--i>

t04>l- jttr-

e

eX

K

_

=g,a_'_0zp=_

=_0

=

4

j

,gk

'

'

,

'=

r

,_

JS

!_

_

2

!

S

>=^=rr_o_-X_

O O O O O O O O

dolcess

S

O D

S

_

;

Jw

t

>

I

'

O O St

S

't

D

S-S

S

S

>_

V

'

_

o^

-

_

.__

---^-gr-S--

t8' '^ O ° t'

It-

-

- '-

_

''-

S

z

°,

1

tg

°

_ =

*,f X °

°

-

=

,-

Music exampleA (ii): Le mclldelpclys,bars20-27

pearsin the middleof Lemaldt pays.The music thatopensLe malis found

in No. 2 of Fleursmelodiques,also in the key of e minor, butthere another

melody appearsat bar 18, markedAllegro Vivace, and the piece, which is

160 barslong, ends in G. The 1855 versionis exactly 70 bars long, andends

in thetonic e minor- butwith anunusualfeaturefoundhardlyanywhereelse

in Liszt's music (at least, to my knowledge):duringthe course ofthe piece,

the key signaturechangesfromone to two sharps,andrenainsfor the return

ofthe e minoropening(Music exampleB). Thus, althoughthetonalityofthe

l C>=it

R

il'_

___;

,Vs

4 P69-

P, -==:,

)X"?

o

X11

X

!

Music example B: Le n1clldu pcly.v,bars65-70

final cadenceis e minor, the tonalityof the key signatureis still the b minor

ofthe earliermusicalsection(MusicexampleC). This ambiguityis reflected

in the unusualharmonyofthe cadence, in particularthe progressionfromA#

to E in the bass - Liszt seems to be referringto the "wrong"key signature.

Whatwas Liszt's purposein retainingthe two sharps, when he frequently

changesthe key signaturein his workseven for shortpassagesoftwo or three

bars?The answer, I believe, is thathe wished to relatethe tonalendingof Le

maldtlpaysto the B majorof Lesclochesthatfollows. Liszt is implyingthat

Slildia Musit f)JoewicLJ

.4 LIdelJ)iae.ScqienliLlrltlJ)

Il#/,czricae

39. 199($'

cantocspr.

\

assal

<-

l

[

TheRoleof Tonalityin theSliss Bookof Anneesde Pelerinage

,

-

47

,\luiss

Lo

Se

-a '

|0EHW

1 sU

I

tS

,

rl tsgrhl.

!

41.>l:sl<:

4e

Wf <

*

f

,,

S

|r$ ' _L--<j mS

*

i

SS

371

.>

_,D,00DOD

A

ae ilalo

.

/t /<oRt)-<

1

'>;

!

:,:.

_rvom

.

bars47-54

Music exampleC: Le mclldzlpctysw,

the majortonalityof the9thandfinalpieceof thecycle resolvestheminor

tonalityof the 8th piece - B majoris to resolvee minor(b minor).As

"heaven",thekeywouldalsorepresentthelongedfor"home"expressedin

of thejourneythatunderpins

Lernaldupays, aswell asbeingthedestination

the wholecycle. Tonallyspeaking,B majorhereis the programmatically

"correct"resolutionof e minor,in whichcasethenormalresolutionof E,

- whichwe know-,beis "incorrect"

whichoccursattheendof Obermann,

causethatpiecedoesnothavea "happyend".

InLiszt,it is usualto progressfromtheminorto themajor.Thereare

piecesthatbeginandendintheminor?of course,butI knownonethatbegin

inthemajorandendintheminor(whichis notunknownin Romanticpiano

music,forexampleChopin'sNoctttrneOp. 32 No. 1 in B endsin b minor).

If the ninekeys of AnneesI area connectedsequence,we wouldexpecta

similarprogressfromtheminortowardthemajor.Letus see thesequence

again:

1. C 2. AN 3. E 4. Ab 5. c 6. e/E 7. AS 8. e 9. B

C is followedby c minor,andE is followedtwice

Wearedisappointed;

of

ofthe tonicminoraftertheestablishnaent

by e minor.Theseinterjections

in termsof content;optithe majorkey representa significantdisturbance

must,in termsof Liszt's

there

and

aside,

are

brushed

and

tranquillity

mism

reasonsforthisfeature.Wehaveto

be "programmatic"

tonaldramaturgy,

of e minor,and

considerwhytheE of Pastoraleis followedby appearances

by thec minorof Orage.

whytheC of Chapelleis disturbed

it uto 3(v./ 'v9A'

iScieltlictltb71Httr1yaJ

iSltdictMu.sicolozyica Ac cttlLsr7licte

372

PalulMerrick

Theonlystablekey(apartfromthesingleappearance

of B) is Ab which

appearsthreetimes.If A is the"love"key, we mustsearchfor its significancein thethreepiecesAulac de Wallenstadt,

Aubordd 'uneso2erce, and

Eglogue.

Aulac de Wallenstadt

is mentioned

by Maried'AgoultinherMemoirs:

"theshoresof the lakeof Wallenstadt

keptus fora longtime. Franzwrote

therefor me a melancholyharmony,imitativeof the sighof thewavesand

thecadenceof oars,whichThaveneverbeenabletohearwithoutweeping."8

Thebeautyof the pieceis remarkable,

andthisreferenceby Marieis evidencethatthe key of A; in thispieceis associatedwithher. Therearetwo

manuscripts

whichaddfurthersupportforthistonalconnection.Thefirstis

anunpublished

Waltz

a MarieinAbincludedaspartof a letterLisztehroteto

herin 1842;9thesecondis a 12barfragmentin A; mentionedby Adrienne

Kaczmarczyk

in herarticleon Liszt'ssketchesfor a plannedcycle entitled

Marie!Poeme.'°Threepieces of music in AS directlyrelatedto Marie

d'Agoultis enoughto confirmtheassociationhereatworkof as thekey of

love. Acceptingthis,we areleftto ponderthewaterconnection- twoof the

AS piecesinAnneesI arewaterpieces(significantlyLisztnumberedthem

togetherinAlb2om

as 2a and2b).Knowing,aswe do, thereligiouscontentof

theendofthecycle,thenhereatthe2ndpiecewe areentitledto looklorsimilarreligiousassociations

- in thiscasethoseof loveandwater.A directexpressionof thisrelationship

is foundin BaptismafromSeptemSacramenta

(S52/R530,1878).In the sacramentof baptism,waterandthe love of the

Holy Spiritarecombined.Thisis probablywhy Lisztmodulatesfromthe

tonicC majorto Al whenhe setstheword"baptizeris",

andwhy A; also

reappears

atthewords"quidatusestnobis"in thesection"CaritasDei diffiusaest in cordibusnostrisperSpiritumsanctum,quidatusestnobis"(The

loveof Godis diffusedintoourheartsthroughtheHolySpirit,who is given

to us) (MusicexampleD). [Inthissectiontheproximityof B andA;is again

8 This quotationfrom the Menloiles, 1833-54 of Marie d'Agoult ("Daniel Stern"), ed. Daniel Ollivier,

Paris 1927 is foundin English in Searle, Hulllphrey:T/leMusicof Lisell,New York 1966, p. 26.

9 The Valsea Marieis reproducedin Gut, Serge: Nouvelle approchedes premieresoeuvres de FranzLiszt

d'apreslacorrespondanceLiszt-d'Agoult,kSkudiaMusicologica

1986, pp. 243-244.

l°See Kaczmarczyk,Adrienne:Liszt: Marie,Poeme (A PlannedPianoCycle), .JAL.N

[.Joure1al

of theAsnerican LisLtSociet!;]Volume 41, January-Ju1le1997*pp. 88-101. The authorquotesfrom a letterof Liszt to Marie

d'Agoultdated8 February,1843:i Next sumlllerwe aregoing to bindAlbumsnarioti4ue.I am very muchdelighted

with this ideaof yours." She adds:iiThe piece referredto in the sketchbook.a tezelve-barsequence in 4 4 and Ab

majorinscribedAlbll/11

nlariotiqlle would probablyhave been includedhere.' (p. 94)

.Slt,JiL,Mtisitoloeicc

4CredewIicze.Scientir7rulJl11zd11,e,aricze

3'). 199S'

(

tt

a.,

l

jl

l

-

-

X5{s

<

l

.

=

! 1 <e 5-

<

Jaw

-

r,}

-

---*

E.

z

w

.s

_._!_

tz

-m--a-ll

_

a

-t

-r

wv

>-

373

TheRole of Tonalityin the Sw1i.ss

Book of Annees de Pelerinage

st},tt

t

derellOf

-

i

M.

^

" tJ

bu-

pti

gg

Sgl'

- f",

1

.

rt

s

A

'

tew

'-.,

.

S

,

Xa

1

-

u

^

.

-

-

bl,

ri,,

-

*ft{.

-

' ffi

I

,,

-

p-j

z

Lc

6t

I

- tu

*

.

I

r)s,

/

K- n

-

s

5 {1

r^s,

Jc

t

*

b . pt i . ; c

S

.

I 1

.

4

A

X

r t

ris,

4

^

4, {

.

{ oi .

_

, ,i§,

b^.

5n_

.

. pe^.

ge.

. zc .

, rau .

-

.

.

. t.s,

,s,

.

'

RWg

_*

}

C ti O R

_J

rc*cs

w

-

-

*

;

I

r

-l

-

[] r .

r,_1

|

h

'

'>

-.>_

>

t 1#

i> r

,,

! 1eo

sel 6¢ ! Zaz

j

b;X.ptl

r]

.-

>

na,

ft,

ba . pt X

c . ,=

si gc ! Za14.

|

CHO/

I

i.e,tWs;t_s t

tva ptz

5cz 6 * .

ze

tn

S

.

.

. ris,

- /t/

;?

i

!):

,7,

. ,,

\

-

ba.pli

2c.

ns,

'-

Nl

. ze.

,

;

bu.pli

ses

gc

.

tnu.

.

,

J

Obeno (SchlXorer/Z. & snd r:. raterio

ttX- r t

| .- R

-$y

-

t'-2

.

. ris.

z

ll

JcZ

!

2G/,

.

{teso.

l

Wiifj fRt

d')

t

trs

f

1.

C

t

-

;

t

T

X

,

S

w

H

i 1 32=j7j5-

Music exampleD (i): Baptisma(>o. 1 of SeptemSacran1enta),

bars 17-36

Music example D (ii): Baptisma,bars60-74

.WlzazSiu

Mu.sicologis a .4ca(Je>sniuc}

Scies2tius tzel2Hzlwul-icue 3 9. / t99.S'

374

PatzlMerrick

an associationof heaven and love. ] The evidence is enoughto infer thatfor

Liszt the presenceof watergave music in ANa religiousaspect. If this associationoperatesalso in S u bordd 'uneso2lrce,

thendramaturgically

thediflerence between the two pieces - thatthe f1rstis still water,the second MC)Ving

water- canbe seen to affecttheprogressofthe cycle, especiallyif we associate movementwith life, or spirit.Thisdifferenceis mirroredby the epigraphs

thatheadthe score of each:Au lac de Wallenstadt

has the inscription:

... thy contrastedlake,

Withthe wild world I dwell in, is a thing

Whichwarllsme, with its stillness, to forsake

Earth'stroubledwatersfor a pul-erspring.

(Byron)

while Au bordd 'unesourcehas:

In SauselnderKuhle

Beginnendie Spiele

Derj ungenN atur.

(Schiller)

The key words are "stillness"in the f1rstepigraph,and "Beginnen"in

the second, since Wallenstadt

is partofthe musical"scenery",andsollrceis

follosvedby musical"action"(Orage).

The thirdpiece in AS,Eglogue,hasbeensurroundedby some contradictory infornzation.The questionof its datehas alreadybeen mentioned.Regardingits contentwe are told, for examplein the Prefaceto the New Liszt

EditionSeries I Volume 6, thatit "is an arrangementof a Swiss shepherd's

song". Accordingto Kroo, however, this is not the case. 1l My own opinion

is thatthe main thematicmate1^ial

of Eglogueappearsfirst in bar 6, and is a

very clear statementof what in my book I call Liszt's Cross motive.12This

motive, which occurs throughoutLiszt's careeras a composer, butwith increased intensityduringthe Weimarperiod, is given special mention in a

noteatthe endofthe score ofthe oratorioTheLegend

ofSt.Elizabeth(Music

0] See Kroo: Annees/Versions, Studia Musicologiccl1992, p. 412. In a footnote Kroo quotes tlom W.

Rusch, F. Lis-t'sAs7neesde Peleris1age,Bellinsona1934, p. 17: "Das Allegro final aus dem Troi.s4irvKSui.s.se.s

erscheint wieder ill 'Egloguet' . Kl oo adds: '*The similarity, however, concerns only the begilmillg of Eglog2lealldit

is too general. It would be quite wrong to suggest that Eglogue was a version of this work. '

12See Mel rick: Relpollltiosl/Lis7t, pp. 284-287, where examples are given of Liszt's hal monization ofthc

motive e.g. C'rX-fidelisin the symphonic poem Hus7Z7eslsc17klcht.

The sequence of chords used there (1! Vl, IV) is

found ot'ten - inciudillg 11erein Eglog2le.

iSzudit7

Musitolt9seictl

XttlLltw2liae^Stienlilrulal

Ilitlt,gariz

t7e3). 1')9N'

fiU gebraucht ist:

zunl Reispiel

us

dem i,

..

---

;

a, d,Zl ji)rnllus

i?

>

. | otc._

TheRoleof Tonalityin theSiss Bookof Anneesde Pelerinage

375

exampleE (i),(ii). It appears10timesin Eglogue,in thekeysof Ab andC,

thusfiulfilling

theroleof a bridgebetweenthosekeys(e.g. betweenCl?upelle

andWallenstadt).

Itsappearance

inSnneesI in Abafterandbeforemusicin

e minor(Obermann

andLe mal dupays) is paralleledfor examplein Les

Morts,the firstof the TroisOdesFunebres(S112/R429,1860),wherethe

firstof fourappearances

of theCrossmotiveis in Ab (in a piecein e minor)

atthewords"HeureuxlesMorts,quimeurentdansle Seigneur!" (MusicexampleE (iii)). TheByronicepigraphto Egloguesays:

The mornis up again, the dewy morn,

Withbreathall incense, aladwith cheek all bloom,

Laughillgthe clouds away with playfulscorn,

And living as if earthcontainedno tomb, - . . .

Sthttsssliclxsci ]\0e)1bl llwerktd:lis elie Ir.lollatloltS

';

'

e;t

* f4'

1-1 iln g-ra8torlulllschen

GCWSUD,,^

schr hau-

Cout

(^t

[l . dc

.

tj

Der CorTponistdieses \NerS;cshalt die niihfr.liche'rnnfolge meErm.alb

ervendel_

anter andern in der

Fu¢e des G3orias

der Craller hIessc; im Schlu>schorder Dantc Sinfouic, und

in dPr s! s!lphorlischexl

I)ichlul ,,Die Hunluen.Sehl3cht." _ Sie bildet, in der oUlie;gczldenCompositioll

ler Leende der heiliDen Elisabeth, gleithcaln a1; to1listhts Sx subol d¢s lire:uzes, das lIrtup(laotif

des Chors der )^;reuzriter(ti') 1Jl a) Utli des Dens ¢.Stancbo (.5° E d)

f,,rum

.s4iCto

.xf)l'r8{2

fJ

Music example E (i): Note referringto the "tonischesSymbol des Kreuzes"

fowld at the end of the full score of the oratorioTheLegendfvfSt.Eli-aheth

(§

t

;

cogl

'

i.

;

tsoto

<

2L,b (g >_

ttv --!

Xb'

Allebrclto

'

s

J 0 l a)23

=Fk

-°

<' =,-r

;} -

e-

-<z!

;-o

8

=:-

L

E

l

J a

P-¢2>'<--S--L

;

g

E

y#-=51;<

R_'2

Music example E (ii): Openingbarsof Eglogzze

.VttlC/iCt

Mt2.sis olvgis ct .4c ctclevenicte

.Sctesitlic/ ttt Httltsctr tt ctev3 9. 1 99,S'

i3[lt->-.

2

Hp

5-

g

i

tk

4

Parll Merrick

376

(L<nto 3szil

(

(_Sf

tIcu

dotr0ssrtnw

rcux

Ct-}-II

f

les

NJ>^

w_

Slorts,

--L;

-4

_r

ntenuto

qui

mcur

ent

_ t__

X

xr

_

daru

t

te

Scigrour!

>,

4

-s

-

_

t

_

_

_

{

-

Music example E (iii): Les Mortss(piano score), bars22-27

To give thesewordsa religiousinterpretationis not difficult;thereis the

presence of'iincense" and the earththat "contain'dno tomb". Whatis the

"morn"that"contain'dno to1nb''- if not Easter?This surelyis the religious

contentof the piece (redemption,resurrection),whose finction is to act as

the catalystfor the whole cycle, makingthe song quotedin Le n1aldupays,

which follows Eglogue, the psychologicalturning-pointwhere Liszt identifies the "home", andmoves away from E to B. We see here how the whole

of Annees I, in its new organization,has been derived by Liszt from this

song, since before composing Orage and Eglogue he must have already

given the song its new interpretation.The pointat which this happenedand

whenLe n?al acquiredits pivotalrole in the cycle, vas the momentwhenS1bumbecamesuperseded,or in Liszt's terms, "invalidated".

Lenal dupayssumsupthe religioustonaldramaturgyof AnneesI. The

song quotation,both in 1&36and 1855, is in two parts)tlle first in the tonic

minor, the second in the tonic major. In the 1855 piece, the song is quoted

threetimes. Two ofthe statementspreservethe minorto majorlaormat,

thus

gXandb areeach followed by theirtonic majors.Thethirdstatementhas only

the second sectio1l,omittingwhatwould havebeen in e minor.The threemajor key sections arethereforeG#,B) and E, but as G#is enharmonical]yAb,

thenthese threestatementscover the keys of love, heavenandre]igion. The

enharmonictransformation,in the overall tonal context of AnneesI, of AS

into G#[see Ex. A (ii) bar 2 i] is such a rarityin Liszt (I know of no similar

example in Liszt - unlike in Chopin, who oficenvvritespassages in enhar1nonic"impossible"keys like E# majorforexample,insteadof F) thatit must

be symbolic. [Liszt'sno1malpracticewould havebeen to writethemajorsection in flatnotation.]Relevantto any considerationof its symbolismmay be

the factthatit appearsvithin the key signatureof five sharps,i.e. of B. Here

we shouldalso observethatthe firstnote (soundingwithoutharmony)ofthe

StzJdio1t1zes

itolo,giec1

QcudelJlirle

.S'cies1tiarallz

lltle1,¢asicae

39 199b'

TheRole of Tonalityin the S :ilss Book of Annees de Pelerinage

377

B majorcloches is againG#- as thoughLiszt wantedto carryover the reference-the tonaldramaturgyofthe whole cycle resolvingintotheenharmonic

changeof A; into G".Afterthis transformation,it is logica]thatLiszt should

omitthe A; section(in Cloches)foundin Altun. Furthermoreit illuminates

the tonalrelationshipof a thirdthatconnectsthe keys of C, Ab andE, where

eachtonic, by becomingthe mediantof the new key (e. g. C is firstdoh then

me) gives rise to the progression.In the case of Abto E, the changeto GW

is

necessary (within the plactical conifines of notation). This enharnaonic

changematchesthe key symbolism(E as religiontransfo1msASas love, the

"new"love [G0])f1guringin cloches orB as heaven).The omissionof e minor

in Le mal dupays may be explainedby the tonal functionof the whole piece

mentionedearlier- thatit resolves e minorto B major.Liszt thereforeavoids

a sectionwhere E majoris p1^eceded

by e minor,restingcontentwith the major tonality alone, and its symbolism. Is it coincidencethat the numberof

barsin this piece is just 70, in years the Biblica]lifespanof a man?

In Liszt's mind,therefore,the compositional(tona])dramaturgyof Annees I deried backwardsfromLe mal dupas following on from the contentof the quotedsong. Thus"homesickness"is precededby (i . e. produced

by) the Cross motive. The Cross motive is preceded(produced)by the despair of Vallee d Obermann.The despair of Obermannis preceded (produced)by the stormof Oage. The stormis preceded(produced)by the active waterof 24ubordd unesouszce.The activewateris preceded(produced)

by the (peasant)animationof Pastorale. The peasantanimationis preceded

(produced)by the still waterof Su lac de Wallenstadtandthe still v:ateris

preceded(produced)by Chapellede GuillaumeTell. We are now at the beginningofthe cycle.

The early version of Chapelle differs in some respects from the later

version, althoughthe tonalityis the same. The sequenceof chordsthatbegins the version in 24nneesI is rnissing.Also, the mainmelody is markedin

the earlyversion(Adagio)religioso. The openingchordsof 1855 seem to reflect the motto thatheads the score: "Eineriiir Alle - Alle fiir Einen"(One

for all andall for one), whichKro6says is a paraphraseof an idea in the New

Testament.13 The connectionwiththe Bible allows us to concludethatthecycle begins in a church,the key of C markinga naturalstartingplace lor a "to13 See Kroo's tableof mottoesin sIsaslees/Versiozls, p. 417 "A paraphraseof an idea in the New Testanaent

(Letterof Paultothe RomansV, 18-19; andthe firstLetterof PaultotheCorinthians,7, 14-15.) ' To Kroo's Bib-

,slt/2iU

Altl.sicologica16adesw1li

es^Sciel?tiurlltJl

Htle1Wuritutv

39 IQ9,S'

f

I

L

Patll Merrick

378

naljourney"(as it does in moreorthodoxcircumstances,like a set of studies,

for example). In which case the move from the C of Chapelleto the ASof

WallenstacXt,

fromchurchto water,parallelstheprogressionfromC to A S in

Baptismamentionedearlier.Aflcerthis, the arrivalof c minormarksthe first

pointof real dramain the cycle.

The openingof Orageis virtuallya quotationofthe openingof Maledictionfor piano and strings(S121/R452 c. 1840), where the themerepresents

the curse (music exampleF). [A version of this theme also opens the symphonicpoem Promethells.

] Of course, mountainstormsin Switzerlandcan

be fairly spectacular,but here we are dealingwith musicalpsychology, not

meteorology.The quotationlrom Byronthatheadsthe score reads:

Butwhere of ye, O tempests!is the goal?

Are ye like those withinthe humanbreast?

Or do ye find, at length, like eagles, some high nest?

The storm"withinthe humanbreast"accountsfor why the maintheme

Qlln.i

rtlo(tcrnto.

{ . \ i u l i ll e ll, ) r-

--

2. Violillel. t'-6_it

I3ratsehen. 4,>

v

-

f

¢ --_

m

t

'

-

--

S

L-- - _--

-

$=

_

t2Unsi moderato.

8<

W6

if

E'ianoforle.

tt

,gmaret;.tw.

(

N) S i' :- 5-

t

\'iololocll.

tt-='

5

, e

rf I

H_-

&

=M,.i=

V<

<

tn.

r -

t.1.

};ontratassel

K

j

t

+

0

-1

wt

r'

rtnerec!lw.

t3.

ot

t

'

-

_.

g

V

l

o

-

-

-I

@

;

-X

<

Quaci moderato.

Music exampleF (i): Openingbarsof Malediction

lical referencesI would add anotherverse from St Paul, I Cor.l9:l) "Justas a humanbody, thouo,hit is made

up of many parts, is a single Ullitbecause all these palts, though many, make one body, so it is vVithChrist.9'

From here it is but a short step to the motto chosen by Liszt for the oratorio Chtistus (Ephesians 4:15). It

verse 16 is added, a text emerges that is rooted in the motto of C/apelle, but can be applied to the whole

Snnees I cycle: "If we live by the tmth and ill love, we shall grow completely into Christ, who is the head

bv whom the whole body is fitted andjoined together,every joint adding its own strength,for each individual

part to >ork accordingto its function. So the body grows until it has built itself up in love."

SttldioMt/sitolo,gicLl

.4t ude9tl)iac

.Scienliurl/tl //l/11eatit ae 3 9. 199S'

Bookof Anneesde Pelerinage

TheRoleof Tonalityin theSmJiss

Allerfo

379

IllOttO

Music example F (ii): Openingbarsof Orage

of Oragebelongsto thetypefoundofteninthesymphonicpoems,including

also in the Faust Symphonyandthe Piano Sonata in B n1inor.Likemany

worksof theWeimarperiod,thedramaofthispiececanbe viewedin terms

Relevant

(thecursebeingaparalleltotheFallinChristianity).

of redemption

tothisis thefactthatitbeginsonaunisonoctaveA; - changedfromthetonic

of c minor.Lisztevidentlywishedto carryover

of source to thesubmediant

thesymbolismof thekey to a merenote. Thisis nottheonlyinstanceinyInnees I of suchcondensedthinking,nevermindthe countlessexamplesin

otherworks,especiallythelateones.A moredetailedtonalanalysisthanthe

withina singlepiececlearly

presentonewouldrevealthekey relationships

to thesameassociationsseenhereoperatingon a largerscaleas

conforming

of A; andE (withoutchangeof

basictonalities- forexamplethealternation

keysignature)in Wallenstadt.Anyattemptto getbehindthenoiseof Orage

thekeysusedby Liszt.

to finda seriouspurposemusttakeintoconsideration

The piece oscillatesbetweenc minorandF#,betweenkey signaturesof 3

flatsand6 sharps.It cannotbe withoutrelevancethatthereare manyinstancesin hisworkswhereLisztassociatesF#withthedivine(intheByronic

epigraphtheeaglesandthe"highnest").

to the

Sucha movefromsceneryto psychology,fromthepicturesque

dramatic,leadspointedlytothecentralpieceofthecycle, Obern1ann,andits

by theE tonalityof Pastorale.

of thepeasantjollityrepresented

shattering

Thatthef1rstpiecein E shouldbe calledPastorale is strange,because

Lisztchosethekey of F forpastoralassociations,perhapsin reveryoiScen

sponseto theinfluenceof Beethovenin his 6thsymphony.[Anexampleis

Paysagefromthe TranscendentalStudies.] Lisztchangedboththe key and

thetitlewhenhe includedPastorale in the 1855cycle. Thechoiceof E here

is a conspicuousone, matchinghis choiceof A;fora waterpiececomposed

forMaried'Agoult:thekeyitselfhadsomethingto contribute.If E is there.sttiCliCZ

MI#.S;COII)g;CgJ

.4

caclezniacX,SceSlltial-zzillHze17guicrIc}39 t99.S'

*

380

r

Pzll DIerrick

ligiouskey)thentheinferencewouldbe thatwe arewitnessesto a religious

scene an animatedone matchingthe occasionreflectedin the earliertitle

Fete Villageois.Perhapsin 1855themusicof 1842was meantto portraya

villagesaint'sday,or churchfestival(theFele of thefirsttitle)andthenew

titlePastoralereflectssimplytlle ruralsetting- its pictorialquality.This

wouldexplaintheapparent

disparitybetweentitleandcontent:herethetitle

givenbyLisztputsthetonality(andwhatitsymbolizes)intoa context,rather

thantheotherwayround(wherethetonalityreflectsthetitle).Thecomposer

seemshereto be watchingthedancingpeasantsas anoutsider,perhapsbecausetheyarehappy.IntheObermann

sense,theyarenotrealpeople,only

partof thescenery.RealitystartswithOrage.

Valleed 'Obermann

is the only piece of the cycle to containthematic

transformation,

thee minorthemeofthe openingappearing

transfigured

in

E at the end. Whenit was publishedin 1855Lisztexplainedin a letterto

Schottthathe includedthe piecebecausethe noveltakesplacein Swtitzerland,butthatits interestis notscenic,butpsychological.He tookexception

to thepictureof a mountainlandscapeon thetitlepage,saying';thereis no

placeforgunsandhunters"14 Inthesameletterhesaidthepiece"relerssimplyandsolelyto Senancour's

Frenchnovel,Obermann,

theactionof wthich

is formedby the developmentof a particularstateof mind..." Liszttoid

Gollerich:"Obermann

ist das Monochordder unerbittlichen

Einsamkeit

menschlicher

Schmerzen.

"t5[WeshouldrecallherethatLisztgavehis late

arrangement

forpianotrioofthepiecethetitleTristia.] AlthoughObermann

endsinthetonicmajor,thusrestoringthelostE of Pastorale,a sharpdissonanceattheendtellsus theattempthasfailed,as it plungesthemusicback

intodespairto makea bittercadence.Itis atthispointthattheCrossappears

n eglogzwe.

WhenLisztmovedLesclochesde Genevefromitspositionas thethird

pieceinSIbumto beingtheculmination

of SnneesI, he alsoalteredthemusic, puttingthewholepieceintoBnzajor,andaddinga newthemeforthesecondhalf.ThesubtitleNocturnestandsattheheadof thescore,andthereare

noepigraphs.Theearlierversion,howevel-,hadtwoepigraphs,oneFrench,

14Letter to Schott [Dr. Edgar Istel: Elf ungedruckteBriefe an Schott, Die Musik, Bertin und Leipzig,

1905-1906, JahrgangV Volume XIX, Booklet 13*p. 47] quotedin the Prefice to the Nels} Li.s-tEdition2

Series I

Volume 6 p. XI.

15Quoted in Malggrat; Woltoang: Eine Klavieltrio-Bealbeitungdes iiVallee d'Obermann"aus Liszt's

Spatzeit,StadiaMllsicologica, 1986, pp. 995 302. TakenFom AugustGollerich:Fsan Lis7t,Budapest1908.

StudiuMositoZogica.4cadeluliaevScienfiurum

fll8zgaricac39. 199N'

TheRoleof Tonalityin the5)1tissBookof Anneesde Pelerinage

381

one English,plus the dedication"a Blandine",the daughterof Lisztand

Maried'Agoultbornin Genevain 1835.TheFrenchepigraphreads:

... Minuitdormait;le lac

etaittranquille,les cieux etoiles...

nous voguissons loin du bord.

TheEnglishby Byronreads:

I live not in myself, but become

Portionof thataroundme;. . .

The 1855 subtitleNocturnepreservesthe 1842 Frenchreferenceto

night,butwhatof theByron,whichseemsto referto theexperienceof becominga father?ThenewthemeoiT1855 is radiantlybeautiful,andbearsa

to partof theMarchof the ThreeKingsin the oratorio

familyresemblance

Christus(MusicexampleG). TheLatintextfromMatthew'sgospelin the

scoreof themarchatthispointreads:"Eteccestella,quamviderantin Orieos, usql1edumvenitens,staretsupra,ubi eratPuer."

ente, antecedebat

(Andsuddenlythestartheyhadseenrisingwentforwardandhaltedoverthe

placewherethechildwas.Matthew2,9) Herewe havethestar,thenightand

Liszt's useof theB mathebirthof a child- theNativitysceneof Christmas.

ofthecycle

withheavenasthedestination

jormusicin Clochesinassociation

in l 855ledhimto omittheASsectionfoundintheearlyversionof thepiece.

Doubtlessas a celebrationof thebirth,thetwo keysB andAS againrepresentedheavenandlove- Lisztwasnotthefirstfatherto feelhis childto be a

gift of God. [One of his very earliestsongs, Angiolindel biondocrin

(S269,1/R593aLittleangelwithgoldenhair)was composedin 1839as a

of AnneesIthe

programme

16] Inthereligious

lullabyforhisyoungdaughter.

bells,however,founda naturalplace.Elsewherein Liszttheyarea symbol

of heaven01thechurch,forexamplethelatesongIhrGlockenvonMarling

(S328/R621, 1874)which,althoughthemaintonalityis E, hasa sectioninB

(withoutchangeof key signature)in whichthe poet, addressingthe bells,

denWeltlichenKlang"(a

says"einheil'gerGesangumwalletwie schutzend

holy songfloatsas if protectingfromthe world'sclamour);thepoetadds:

"behutetmichgut"(watchoverme well). In ClochesLisztaddedwithout

commenta newthemeto continuethetonalityof B, itsjubilantmoodbeing

left, as it were,to speakforitself.

Leipzig, 1880-1894,

IG SeeRamann, Lina:FraszzLi,ctalsKLinstlerZzdMensch,

,4 c C}2e'11l

,Sludibl

Mt.vic()l)gicBc}

i4t'

volumeI, p. 535.

Sc ievl 11icorl l lwl

Ht1 11gC}riL'C}(!3 9

1 990

j

tu=S,=<fS

S

*

; _

!

_I

oi

382

s

s

s

#

t

.

l

I

-{

1

I

a

!

fX

tf=

Pazll Merrick

ws,,;,liut#.

J

i

!*'

fr(XS-)=t

I

IT ceun

soli nra

[

r)acs,o+le

$:

-J

&,

f <

_- ! !=!

X

_;41

_ fl

<

)>S,AsF

l

|.

8

r^ I

,

°

*-,

b

l

l

= >:

|

';

4

5

}

0?"

>S

,

7-}

d=^:

'-

v

MusicexampleG (i): Lesclochesde Geneve,bars108-123

¢t

2

()

;>

[

r

,T£z¢

s:(93=

f

)t

5

F

hE5

ir r

] z;

gj

L J

Ara

2

1L =

r

i,

-

¢ s s I_;iR

>

5 C

*

ta=.Hg

MusicexampleG (ii):Die heiligendreiKonigefromtheoratorioChristus(pianoscore)

bars334-345

.SludiaMl(sitole)fwiccl

4caJde>l1iae

.SciewnliarulJt

11tl?,earicue

3tH.19'9.N'

TheRole of Tonalityin the S 1tissBook of Annees de PelesAinage

383

A journeyhastwo aspects,externalandinternal,the sceneryandthe

purpose.Thedictionarydefinesa pilgrimageas "ajourneyto a holyplace".

WhenLisztcomposedSIbum,he describedthescenery,butwhenhe wrote

journey,hencehe calledit "PeleAnneesI, hewantedto expressaninternal

pictorial

piecesalreadyin existence,

to the

rinage".By makingalterations

andby addingothers,he couldmakethe pilgrimagea musicalone, partly

of a symbolicuse of tonality.Theninepiecescan

throughthearrangement

Man(Chapelle,

evenbe seenas threegroupsof three,groupI representing

and

Pastorale),groupIItheSoul(Source,Orage,Obermann)

Wallenstadt,

groupIIIGod(Eglogue,Le n1aldupays, Cloches).Thetonaljourneynow

looksas follows:

mantherot ideals, church

C

AN love, still water

peasantreligiousfestival

E

AN love, water, movement(spirit)

storm- in man's breast

c

e/E despair

AW love - Cross motive- redemption

longillg fbr "home"

e

heavell

B

If we omittheC of Chapelle,we see the"tonaldrama"as anattemptto

moveawayfromANtowardsa "goal"- i.e. to expressthe purposeofthe

journey.IngroupI theE remains"static"- a merepicture.In groupII the

c minorbringsmotionandagitation,the"idyllic"E of Pastorale

intervening

In groupIIIthereis no atis lost, andit cannotbe restoredby Obern1ann.

of Eglogueguidesthepilgrim

temptto restorethe"lost"E - theappearance

towardsthe"true"B. Wesee herethe"innerpath"of thecycle?a pathhiddenin thetonalorganization.

Liszt

By involvingtonalityaspartofthe languageof his"programme",

inthethenotapparent

wasabletobuildintothemusica logicaldevelopment

maticmaterialoreveninthetitles.Itis thetonalitythatcontainsthepilgrimage;we mayevensaythatforLisztthesequenceof keysin a senseformed

themusical"ligneinterieure".

Sll(ctt

jJlla8iL>Dle}giLA 4La&112it'.stit'1?liA1-z1121

£ll?gAl'iLt'

3(J

199sS