Wednesday, February 19, 8pm Pickman Hall Cedric Tiberghien

advertisement

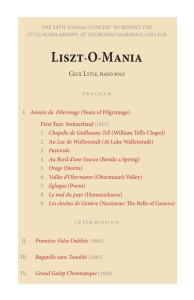

Wednesday, February 19, 8pm Pickman Hall Cedric Tiberghien, piano Notes on the Program Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Années de Pèlerinage (First Year: Switzerland) In the period when he was most active as a virtuoso, Liszt traveled widely, especially during the years 1835-39, when he was living with his mistress, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, who had left her husband for him and who bore him three children (one of them, Cosima, was to become the wife of Richard Wagner). During these years he produced a formidable quantity of music for solo piano. During 1838, for example, he completed first versions of his Paganini etudes, the Transcendental etudes, and a number of works in1841-42 as Album d’un voyageur (A Traveler’s Album), later to be included in his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage), which he published in three volumes. The first (1855) was labeled “Switzerland,” the second (1858) “Italy,” and the third (1883) left untitled. The “pilgrimage” in Switzerland contained nine numbers in all, of which seven bear explicit literary references, mostly to Schiller (from his William Tell) or Byron (from Manfred). Chapelle de Guillaume Tell (“William Tell’s Chapel,” after Schiller) Liszt’s homage to the Swiss folk hero William Tell and to Schiller’s drama bears the inscription “All for one, one for all,” the motto of the Swiss confederation, and opens with a hymnlike passage in modal harmony, suggesting considerable antiquity. But if the idea of “William Tell’s chapel” suggests peace and tranquility, we are soon disabused of that notion, for the score takes on a much more orchestral character similar to the climaxes of his tone poems. Au Lac de Wallenstadt (“At Lake Wallenstadt,” after Byron) A few lines from Byron set the stage for the brief, lyrical depiction of the Lake Wallenstadt, a narrow mountain lake between the cantons of St. Gall and Glarus: …thy contrasted lake, With the wild world I dwelt in, is a thing Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake Earth’s troubled waters for a purer spring. The running sixteenth-note figure, which continues almost without break throughout, and the pentatonic melody evoke the calm of the mountain fastness and the “purer spring” that it conceals. Liszt’s sometime mistress and mother of his children, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, who traveled through Switzerland with Liszt in the first months of their elopement, found it a particularly melancholy piece, one “which I have never been able to hear without weeping.” Pastorale is the shortest work in the collection, a continuation of the rocking “water music” of the previous piece, though somewhat lighter in mood. Au bord d’une source (“Beside a spring”) was, in its earliest version, attached to Au Lac de Wallenstadt, but in the final published version, Liszt gave it a separate identity, prefaced by some lines from Schiller: Im säuselnder Kühle Beginnen die Spiele Der jungen Natur. In murmuring coolness The play of young Nature Begins. The delicate flowing movement, marked repeatedly “tranquillo,” suggests the rushing waters of a spring and accompanying cool breezes. Orage (“Storm,” after Byron) offers a complete change of mood, calling forth the physical storms of wind and rain and thunder as metaphors for the pounding storms within the human heart. Racing chromatic lines (sometimes in octaves, sometimes in parallel thirds in both hands) alternate with pounding chords to produce the virtuosic effect. Again Byron provides an epigraph: But where of ye, oh tempests, is the goal? Are you like those within the human breast? Or do ye find, at length, like eagles, some high nest? La Vallée d'Obermann (“Obermann’s Valley,” after Senancour) Aside from Schiller and Byron, the only author cited in the collection, and only for Vallée d’Obermann, is Étienne Pivert de Senancour (1770-1846), who, though born in Paris, spent the years of the French Revolution in Switzerland, where he wrote Reveries on the Primitive Nature of Man (1799), the descriptive passages of which linked him with the early romantics. His Obermann (1804), which has not been entirely forgotten, takes the form of letters written by a melancholy individual living alone in the valley of the Jura—presumably the “Valley of Obermann” to which Listz’s piece refers. The work is essentially a tone-poem for piano, developing with the imaginative use of thematic transformation, which was to be the principal structural feature of his orchestral tone poems. It traces a path from darkness to light, the opening mood depicted by the rather long quotation from Senancour’s book,which Liszt places at the head of the piece, beginning: “What do I want? What am I? What to ask of nature?...Every cause is invisible, every end deceptive; every form changes…” This mood of emptiness is captured by the slowly descending scale lines of the opening, and the constant questions are echoed by several clear musical questions that interrupt the ongoing development of the downward-moving figure. Before long a more songful extension of the questioning motif appears, and these various materials unfold in an increasingly emphatic, brilliant, dramatic, and colorful way. Eglogue (“Eclogue,” after Byron) follows the powerful drama of the preceding pieces with a more pastoral work. (An eclogue is a poem in classical style on a pastoral subject, often in the form of a conversation about country matters or, more probably here, a soliloquy. A passage from Byron’s Childe Harold provides the expressive key: The morn is up again, the dewy morn With breath all incense, and with cheek all bloom Laughing the cloud away with playful scorn And living as if earth contained no tomb! Le Mal du pays (Heimweh - “Homesickness”) is a reworking of an earlier piece from a collection entitled “Melodic Flowers of the Alps.” The subtitle indicates that it is a musical treatment of homesickness, one that make use of the Swiss Ranz des Vaches, a tune implying the herding of cattle in the mountains (Liszt used it in several compositions). The score is preceded by a veritable essay from Senancour “On Romantic Expression and on the ranz des vaches.” Les Cloches de Genève: Nocturne (“The Bells of Geneva: Nocturne,” after Byron) might be expected to be an extended showpiece of bell sounds, though Liszt is really quite restrained in that pictorial element. Though the music supposedly is inspired again by Byron, the score includes no epigraph, only the subtitle “Nocturne.” Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) Masques, Opus 34 During the middle of World War I—years that marked the beginning of his mastery— Szymanowski composed three substantial triptychs for piano (in one case in partnership with violin); all three drew their programmatic inspiration from classical Greece and other literary images and their musical inspiration from recent works by Ravel, Debussy, Scriabin, and Bartók. Happily a physical disability in his knee got him exempted from military service after the assassination in Sarajevo that triggered the horrors of 1914-1918, and he was able to create a rich body of music in those war years. The first of the works was Mythes, Op. 30, composed between March and June 1915. Even before finishing that work he started on Métopes¸ published as Op. 29, for piano solo, completed in August. Masques was partly composed in 1915 and completed in the first half of 1916. The three movements of Masques have programmatic titles, and the listener may occasionally hear hints of a literary character in the music, but there is little attempt to tell stories. On the contrary, Szymanowksi manages in these three pieces to draw into his own musical world ideas that he had heard from the leading composers of the day—the sensuous color of the French impressionists, the dynamic pounding rhythms, colored by folk characteristics of a Stravinsky score, the perfumed harmonies of Scriabin, and the sarcasms of the young Turks who were near his age. The work was premiered in St. Petersburg on October 12, 1916, by Sasha Dubiansky. The three movements are dedicated, respectively, to Dubiansky, Szymanowski’s cousin Henryk Neuhaus, and his friend Artur Rubinstein. Shéhérazade is, of course, the enchanting tale-teller from the Thousand and One Nights. She begins by captivating the brutal caliph with a sensuous and sinuous dance, but soon she starts telling her tale against a 6/8 trill in the left hand. Though the composer offers no hint as to the subject matter of her story, it is one that clearly builds to a forceful climax, then, after a respite, to a still more powerfully accentuated and frenetic second climax, before dying away in the lightly sensuous mood of the opening. Tantris le Bouffon is a kind of parody of Tristan—at least in its title, “Tantris” having been the false name that the knight adopted in the prehistory of Wagner’s opera, when Isolde first met and fell in love with him; Szymanowski found the title from a 1908 book, Tantris the Fool, by Ernst Hardt. But musically it also seems to start as an homage to Stravinsky’s Petrushka, which Szymanowski had heard during his youthful travels. He had declared Stravinsky a genius and had played through Petrushka in a piano 4-hands version with his good friend Artur Rubinstein. As the piece proceeds, it reaches a height of sarcasm à la Bartók or Prokofiev. Sérénade de Don Juan begins with an introduction in which the narcissistic lover and serenade indulges in an attention-getting process of tuning up his guitar. The serenade proper is basically in rondo form (appropriate to the personality of a narcissist who lives entirely the celebrate himself), and the piano imitates the guitar quite virtuosically. Don Juan’s serenade becomes grander and ever more hopeful until the final chord, which—as Christopher Palmer notes— “sounds uncommonly like a window being banged shut.” Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Miroirs Ravel composed Miroirs (“Mirrors”) for piano in 1904 and 1905. Ricardo Viñes gave the first performance at the Salle Erard in Paris on January 6, 1906. The overall title “Mirrors” suggests the intention of reflecting reality in music, and each movement has its own pictorial title. Ravel had learned, via Ricardo Viñes, of a remark Debussy had made to the effect that he wanted to write music so free in form that it would appear to be improvised. Ravel was utterly taken with this idea and applied it in Miroirs. Noctuelles (“Night Moths”) suggests the flitting of these tiny insects by means of a very light touch, frequent changes of meter, and brief runs outside a measured meter. This gives a very free rhythm that would create the kind of improvised effect that Ravel sought. Ravel himself considered that Oiseaux tristes (“Sad birds”) marked a significant change in his harmonic development, and it may have been the first piece he composed after hearing the remark of Debussy referenced above. “I evoke birds lost in the torpor of a somber forest,” Ravel wrote, “during the most torrid hours of summertime.” It is based on a number of bird calls and avoids resolution to the tonic until virtually the end of the piece. Une barque sur l’océan (“A Boat on the Ocean”) is the longest work in the set and becomes a kind of etude in arpeggios against a thematic thread. Alborada del gracioso (“The Aubade of the Jester”) is a lively, Spanish-flavored piece full of rhythm and humor. It is also filled with powerful accents and impossibly fast repeated notes that are a challenge to even the most gifted virtuoso. Not surprisingly, Ravel later orchestrated it, and in that guise the work is generally better known. (He also orchestrated Une barque sur l’océan but was dissatisfied with that version and left it unpublished.) The “alborada” is a dawn-song commonly found in Medieval literature, a song of warning sung by a confidante to warn a pair of illicit lovers that night is fleeting and that they had better separate before dawn arrives. The second part of Ravel's title is uniquely elusive, for this is the dawn-song of the gracioso—a buffoon, a jester, a clown. So this morning song is not the end of a romantic interlude, but rather a vigorous Spanish dance, possibly somewhat comic in character, built up from a typical Iberian rhythm and the frequent opposition of 6/8 and 3/4 meters. La Vallée des cloches (“The Valley of the Bells”) is a study of bell sounds, though not specifically in a “valley” but rather (as Ravel told the pianist Robert Casadesus) the tolling of many church bells at noon in Paris—near and far, their long-resonant ringing overlapping and dying away. © Steven Ledbetter (www.stevenledbetter.com)