James Hazelton - Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee

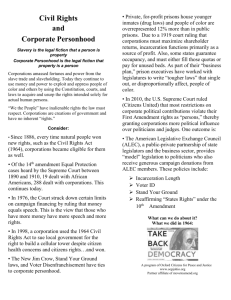

advertisement