Chapter 20

advertisement

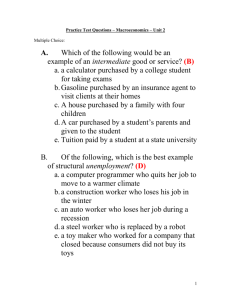

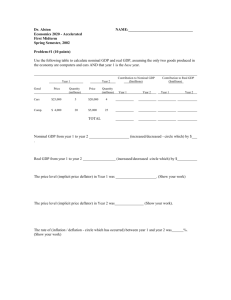

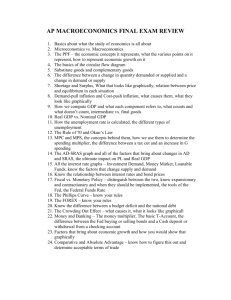

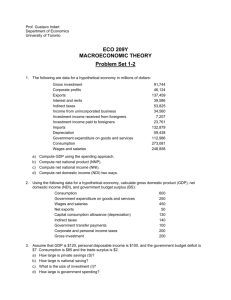

____________________________________________ Chapter 20: The Measurement of National Income ____________________________________________ Answers to Study Exercises Question 1 a) double counting; overestimate b) value added; value added; non-labour inputs c) consumption; investment; government purchases of goods and services; net export expenditures; Ca + Ia + Ga + NXa (subscript “a” for “actual” expenditures) d) wages and salaries; interest; business profits; indirect taxes net of subsidies; depreciation Question 2 a) GDP; GNP b) prices; quantities (real output); base-period; real c) average income per person d) productivity Question 3 a) Automobile purchases by consumers are included as part of consumption, C. They are considered a durable good. b) Automobile purchases by firms are included as part of investment, I. c) Expenditures on new machinery by companies in Canada are considered part of Canadian investment, I. It is irrelevant who owns the companies. d) This is not included as investment in Canada, though it would be considered as part of investment expenditure in the United States. e) Expenditures on new machinery by companies in Canada are considered part of Canadian investment, I. It is irrelevant who owns the companies. f) Reduction in business inventories is considered negative investment in Canada. g) Purchases of second-hand cars and trucks are not included in the national accounts because this does not represent expenditure on newly produced goods and services. 2 h) The hiring of economic consultants by government is part of government purchases, G. i) The purchase of Canadian-made software by a Japanese firm is part of exports, X. Question 4 a) Using the expenditure approach, GDP = C + I + G + NX, where C is consumption (3900), I is gross private investment (1100 = 950 + 150), G is government purchases (1000), and NX is net exports (– 40 = 350 – 390). Therefore, GDP = 3900 + 1100 + 1000 – 40 = 5960 (millions of dollars). b) Using the income approach, GDP = wage and salaries (5000) plus interest (200) plus business profits (465) plus indirect taxes less subsidies (145 = 175 – 30) plus depreciation (150). The total is 5960 (millions of dollars). c) Net domestic income at factor cost is just the total of factor payments, which is the sum of wages and salaries plus interest plus business profits. Therefore, net domestic income at factor cost is 5000 + 200 + 465 = 5665 (millions of dollars). Question 5 a) The GDP deflator is equal to (Nominal GDP/Real GDP) × 100. The deflator for each year is: 1999: 2000: 2001: 2002: 2003: 2004: deflator = (775.3/798.4) × 100 = 97.1 deflator = (814.1/838.6) × 100 = 97.1 deflator = (862.9/862.9) × 100 = 100.0 deflator = (901.5/882.5) × 100 = 102.2 deflator = (951.3/920.6) × 100 = 103.3 deflator = (998.8/950.5) × 100 = 105.1 b) The percentage change in nominal GDP from 1999 to 2004 is (998.8 – 775.3)/775.3 = 0.288 or 28.8 percent. The percentage change in real GDP over the same period is (950.5 – 798.4)/798.4 = 0.191 or 19.1 percent. Thus, roughly two-thirds (19.1/28.8 = 0.663) of the change in nominal GDP from 1999 to 2004 was the result of changes in quantities, meaning that roughly one-third was the result of changes in prices. Question 6 Generally the two measures of inflation will be similar but not identical. Inflation as measured by the rate of change of the GDP deflator indicates the change in prices of goods and services produced in the Canadian economy. Inflation as measured by the rate of change of the Consumer Price Index indicates the change in prices of the goods and services consumed by the average Canadian household. The two “baskets of goods” are different. For example, forestry products (and the goods derived therefrom) will have a larger weight in the Canadian GDP deflator than in the CPI because Canada is a large net exporter of forestry products. Conversely, coffee, sugar, and tropical fruits and vegetables will have a larger weight in the CPI than in the GDP deflator because Canada consumes but does not produce these goods. So, in general, changes in the prices of traded goods will tend to influence the two price indexes differently. But even large changes in the prices 3 of individual traded goods will have a small effect on either overall price index for the simple reason that the indexes are made up of many goods, each good having a very small weight. The two indexes tend to move together because the overall inflationary (or deflationary) pressures in the economy tend to apply to all goods and services. Question 7 a) The increase in the demand for building materials leads to more expenditure on these products. If this increased demand leads to an increase in production of such goods, then GDP will increase. b) The damage caused to factories will presumably reduce those factories’ ability to produce output, at least until they are repaired. Putting (a) and (b) together, we see that the ice storm has an ambiguous effect on real GDP. c) If Montrealers increase their demand for Expos tickets, they presumably reduce their demand for other goods (otherwise the building of the stadium would affect their overall saving rate, which seems unlikely). For example, Montrealers attend more baseball games but attend fewer concerts, movies, or purchase fewer clothes or coffee. If total expenditure is unchanged, it is difficult to see why GDP would rise, though the composition of GDP would surely change. There would be more baseball-game services produced and fewer of other goods and services produced. d) The key point is to determine what people from Vermont and New Hampshire would have done if the new stadium were not built. If we assume that the building of the stadium leads U.S. residents who would not otherwise purchase Canadian goods to now come to Montreal and purchase various goods and services associated with their baseball visit, then Canadian real GDP would rise. But if it is just a substitution away from other Canadian goods toward the Expos baseball games, then there will be no effect on Canadian GDP. In this case it seems reasonable to assume that at least some of the expenditure would be new expenditure, and thus that Canadian GDP would rise. Question 8 a) Nominal GDP is simply the sum of price × quantity for the two goods. The values are: Year 1: Nominal GDP = (100 × $2) + (40 × $6) = $200 + $240 = $440 Year 2: Nominal GDP = (120 × $3) + (25 × $6) = $360 + $150 = $510 b) Real GDP is computed by using the prices from the base year. Since Year 1 is the base year, nominal and real GDP are the same in that year. The values are: Year 1: Real GDP = (100 × $2) + (40 × $6) = $200 + $240 = $440 Year 2: Real GDP = (120 × $2) + (25 × $6) = $240 + $150 = $390 Real GDP falls from Year 1 to Year 2 by a percentage equal to (390 – 440)/440 = –0.113 or –11.3 percent. c) The GDP deflator is equal to (Nominal GDP/Real GDP) × 100. Using Year 1 as the base year, nominal and real GDP are the same in Year 1. The values for the deflator are: 4 Year 1: Deflator = (440/440) × 100 = 100 Year 2: Deflator = (510/390) × 100 = 130.8 The change in the GDP deflator from Year 1 to Year 2 is (130.8 – 100)/100 = 0.308 or 30.8 percent. d) This was done in (c). In Year 1 the deflator is 100. In Year 2 the deflator is 130.8. e) To do this we must first compute real GDP in both years, using Year 2 as the base year. Since Year 2 is the base year, nominal and real GDP are the same in that year. The values of real GDP are: Year 1: Real GDP = (100 × $3) + (40 × $6) = $300 + $240 = $540 Year 2: Real GDP = (120 × $3) + (25 × $6) = $360 + $150 = $510 Now, compute the GDP deflator (base year 2) as: Year 1: Deflator = (440/540)×100 = 81.5 Year 2: Deflator = (510/510)×100 = 100.0 f) Let’s compile the information we have gathered in the following table. Base Year Change of Real GDP Change in GDP Deflator Year 1 – 11.3% 30.8% Year 2 (510 – 540)/540 = –5.6% (100 – 22.7% 81.5)/81.5 = These numbers may look puzzling. Does real GDP fall by 11.3% or only 5.6%? Do prices rise by 30.8% or only by 22.7%? Which are the “correct” figures? This is a good way to understand why the choice of base year affects calculations of real GDP and the GDP deflator. The key point here is that if there are changes in relative prices from one year to the next, then the choice of base year will matter. To understand why, suppose we choose Year 1 as the base year. In this case, the relative price of honey to milk is 6/2 or 3. The very large drop in the quantity of honey produced (from 40 to 25 kg) is weighted heavily, and thus real GDP drops significantly. But if we use Year 2 as the base year, the relative price of honey to milk is 6/3 or only 2. In this case, the same large drop in the quantity of honey gets a smaller weight than in the case where Year 1 is the base year.