The Emergence of Texture: An Analysis of the Functions

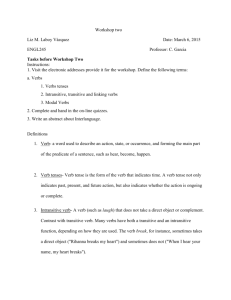

advertisement