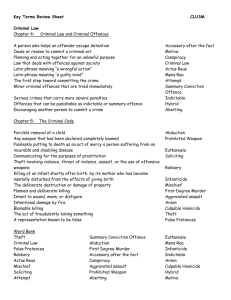

Consultation Paper on Inchoate Offences

advertisement