Originalism as a Theory of Legal Change

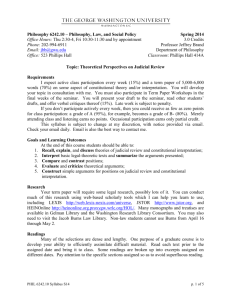

advertisement