Conflict Eng Thesis - University of Jos Institutional Repository

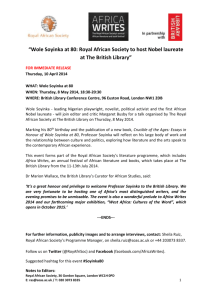

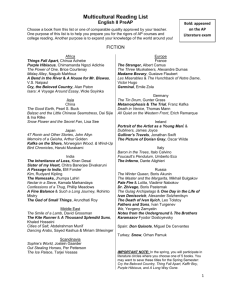

advertisement