quantity, role, and culpability in the federal sentencing

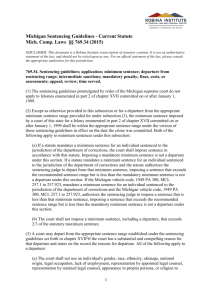

advertisement