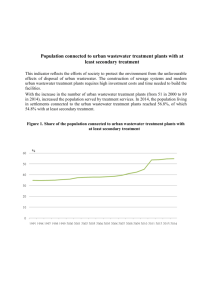

annexe 1: text boxes

advertisement