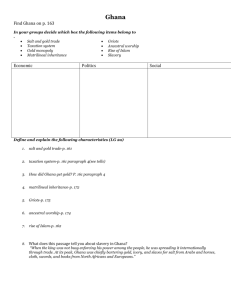

Major issues arising out of industrial relations disputes in Ghana

advertisement