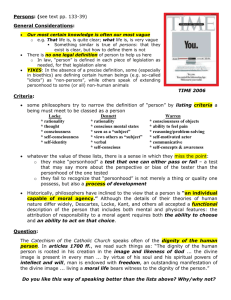

Legal Consciousness and Contractual Obligations

advertisement