How Elephants Learn the New Dance When Headquarters Changes

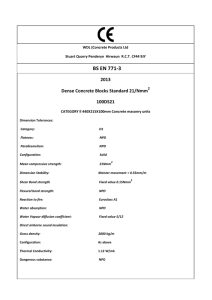

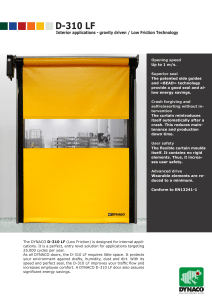

advertisement