Background Readings for Pontiac' Rebellion

advertisement

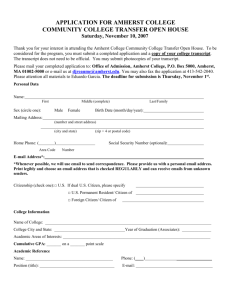

Background Readings for Pontiac’ Rebellion As you read make note of key people and events. Also note the repercussions of the major events discussed on American colonial history. Pontiac c. 1720-1769 Source:DISCovering Biography. Online Detroit: Gale, 2003. From Student Resource Center - Gold. Born: c. 1720 in Ohio, United States Died: April 20, 1769 in Missouri, United States Nationality: American. Ethnicity: Native American. Occupation: tribal commander/warrior, orator. Pontiac forged alliances among diverse Indian groups that set precedents for future resistance efforts among Indian leaders of this region, who, like Pontiac, sought ways to halt settler encroachment on their lands. Pontiac, war chief of the Ottawa and leader of the Pontiac Rebellion of 1763, was the compelling force behind one of the greatest Indian alliances in the history of America. A gifted leader and military tactician, he was the catalyst for the most impressive Indian resistance movement that the English-speaking settlers had yet encountered, or ever would encounter, on the North American continent. Although little is known about Pontiac's youth, it is believed that he was born around 1720 along the Maumee River in Ohio to an Ottawa father and a Chippewa mother. When Pontiac was born, the Ottawa nation was located at Michilimackinac, at Saginaw Bay, and at the Detroit River. As his influence and prosperity increased, he may have had more than one wife and several children. It is known that he had at least one wife, Kantuckeegan, and two sons, Otussa and Shegenaba. Even though there are no recorded events of his youth, it is assumed that Pontiac spent his childhood and young adult years in a manner characteristic of the Ottawa. The first ceremony which would have concerned Pontiac was the naming ceremony. Ottawa babies were not named until they were a few months old. The exact meaning of the name Pontiac has never been determined, but nineteenth-century Ottawa tradition referred to him as Obwandiyag (pronounced Bwon-diac). The English spelled his name Pontiac which was probably the way it sounded to them. As an Ottawa boy, Pontiac was probably taught the skills to enable him to hunt and to survive in the woods. In addition, he was probably encouraged to utilize the weapons and tools used by the white men, which were usually obtained from the French traders and which eventually replaced the inferior native weapons. Doubtless, Pontiac was also taught the customs and traditions of his tribe. One tradition at which he evidently demonstrated a particularly strong aptitude was the art of fighting and making war, from the initial stage of building enthusiasm for battle to the final stage of torturing prisoners. An Ottawa family was traditionally responsible for their child's education, and because there was no formal means of instruction, the families relied largely upon oral lessons and the example of others—both techniques emphasizing practical knowledge. The political organization of the Ottawa nation was simple and unstructured. Each village had several chiefs who served for an indefinite period of time. Heredity did not always play a part in who was selected chief; rather, a chief was chosen based on his capability and his ability to lead others, and he would retain his influence only as long as he was successful in battle. Pontiac's particular brand of authority was such that he was able not only to lead his own people effectively, but he also gained the influence that was necessary to forge alliances with other tribes. During Pontiac's early years, the Indians and the French enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship. The Indians traded furs for French arms and other goods. Through these transactions, the Ottawa gradually replaced their bows and arrows with guns, which became the primary means of obtaining food and ensuring protection. As a result of this association, the Ottawa increasingly relied on the goods of the French traders for survival, and their former way of life was lost. Initially, Pontiac was inclined to be as cordial to the English settlers as he was to the French traders. However, this attitude changed when it became apparent that the English conduct toward the Indians was vastly different from the manner in which the French had interacted with them. In particular, Pontiac took exception to several policies established by Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who was the British commander-in-chief in America. One particularly damaging order prohibited the British from trading gunpowder and ammunition to the Indians, who had become highly dependent on their weapons. Further, the British displayed an increasingly aggressive attitude toward the Indians' land, indicating that they were interested in settling the entire country instead of just establishing military and trading posts. Moreover, the British discontinued extending credit to the Indians. Credit was particularly important because the Indians often needed supplies to survive the winter. When spring arrived, they would repay the debt with furs. Another source of conflict was the attitude of the British toward them; they treated the Indians as though they were an expensive inconvenience. By 1763, the entire area seethed with extreme agitation. Forges an Alliance and Launches Attacks Pontiac believed that if the tribes presented a united front and gained support from the French, the encroaching British could be forced from the Great Lakes region. His objective was to mount one enormous and simultaneous surprise attack on all of the British forts and settlements in the area. Part of Pontiac's plan may have been influenced by a religious leader known as the Delaware Prophet (also known as Neolin). The Delaware Prophet preached the disapproval and rejection of the white man's lifestyle and advocated the return to traditional Indian customs. He depicted the hazards of associating with white men by creating a series of deerskin paintings. The pictures showed the white men impeding the Indians' desire to achieve happiness and prosperity; further, they illustrated the sins that the Indians had acquired as a result of their contact with the white men. While these images had a profound effect on the Great Lakes Indians, a major difference of opinion arose between the Delaware Prophet and them about how to resolve the problem. In his teachings, the Delaware Prophet advocated a resistance to the white man's influence that extended to the relinquishment of their dependence on the Europeans' guns, whereas many Great Lakes Indians—including Pontiac—viewed armed conflict as the only way to gain autonomy from the British settlers. It is also believed that Pontiac's strategy to drive away the British was based on a plan originated two years earlier by the Seneca Guyasuta. In an effort to achieve his goal, Pontiac sent red wampum belts to Indian tribes from Lake Ontario to the Mississippi River, calling them together in a conspiracy to attack all of the British-held posts in the region. Among the tribes who joined in Pontiac's immediate efforts were the Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Missisauga. Detroit, the most important fort of the Great Lakes region, was Pontiac's principal target. In April of 1763, Pontiac outlined his strategy in a speech to three Indian villages— Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Wyandot. He stressed the eviction of the British and a return to a traditional lifestyle. His speech served to provoke the warriors into action. On May 7, Pontiac approached Detroit under the guise of meeting for a council. Upon gaining access to the fort, he was to give the attack signal to his group of warriors who had their weapons hidden under blankets. However, reports of the imminent rebellion had reached Amherst who, in turn, sent reinforcements to Detroit. When it became apparent that the commander at Detroit had his men armed and prepared for the onslaught, Pontiac decided against giving the prearranged signal and retreated. Despite the presence of heavy reinforcements, Pontiac's warriors were restless for battle; to appease his followers, the chief returned to the fort two days later and launched an attack which proved to be unsuccessful. Elsewhere in the Great Lakes region, the tribes that participated in Pontiac's rebellion had greater success. Using various ploys, Indian warriors killed or captured all of the people at Fort Sandusky on May 16, at Fort St. Joseph on May 25, at Fort Miami on May 27, and at Fort Quiatenon on June 1. The Ojibwa surprise attack at Michilimackinac on June 2 was probably the most widely related incident of Pontiac's war. During a game of lacrosse, the Indian players sent a ball over the stockade wall and then all went in to retrieve it. Once they gained access to the fort, the Ojibwa began killing and taking prisoners. In the middle of June, the Seneca joined in the rebellion. First they attacked Fort Venango leaving no survivors; a couple of days later, they attacked Fort Le Boeuf, but the British were able to escape before the fort was destroyed. The Seneca then joined forces with the Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Wyandot and carried out a successful siege leading to the surrender of Fort Presque Isle on June 20. In a little more than a month, nine British forts had been seized and one had been deserted. However, the Detroit post and Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania remained intact. During the standoff at Detroit, the British troops successfully held off Pontiac's combined Indian force of about 900 warriors by receiving reinforcements via the water route from the Niagara. For his part, Pontiac also fortified his Indian force so that the siege gradually turned into a stalemate. In the meantime, at Amherst's suggestion, the British forces at Fort Pitt used a crude form of biological warfare to hold off the Indian siege there. Smallpox-infected blankets and handkerchiefs were discretely circulated among the warriors, which resulted in an epidemic among the Indians in the Ohio towns of Delaware, Mingo, and Shawnee. The smallpox epidemic lasted until the following spring. While Pontiac's war resulted in military activity spanning a large region, the main concentration of fighting occurred in the Detroit area and along the British supply line stretching from Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario, along the Niagara River, and across Lake Erie to Detroit. Even though the losses were frequent along this supply route, some vessels did make their way through to provide necessary reinforcements to the beleaguered forts. Periodically, the British attempted to mount offensives to break the stalemate in the Detroit area. One mission, which occurred in late July 1763, had particularly devastating results. Part of a British relief expedition making its way toward the fort at Detroit attempted a surprise night raid on Pontiac's camp located five miles to the north; however, the Indians were ready for them and they ambushed the soldiers as they crossed a bridge near a small stream. After 19 soldiers were killed and 42 were wounded, the British troops were forced to retreat. The early weeks of Pontiac's war proved favorable to the Indian allies, but obstacles to future success were obvious from the onset. Many tribal leaders were critical of the acts of torture and cannibalism committed during drunken celebration parties at the Ottawa camp near Detroit. Kinochameg, son of the Ojibwa leader Minevavana, traveled from northern Michigan to deliver a speech denouncing the abhorrent treatment of prisoners. In addition, representatives of the Delaware and Shawnee tribes spoke at a council meeting and informed everyone there that hostilities in the Great Lakes area were damaging the fur trading business with their French allies. Furthermore, the military confrontations often generated violence and brutality throughout the region which was not limited strictly to the battlefield. Isolated Indian raids on white settlements along the frontier from New York to Maryland provoked reprisals against Indians who were not even involved in Pontiac's war. Throughout the war, Pontiac remained confident in his belief that the French would ultimately come to the Indians' aid. What the Indian chief did not know was that England and France had already signed a peace treaty in London the previous February. When Pontiac became aware of this fact he lost any real hope that the Indians would be able to win the war. With winter approaching, his warriors were becoming increasingly restless about providing adequate food and shelter for the survival of their families. Also at this time, Pontiac received a letter dated October 20, 1763, from Major de Villiers, the commander of the French Fort de Chartres on the Mississippi River, advising him to end the war campaign. The next day, Pontiac declared an end to the siege of Detroit and retreated to the west, but he continued his opposition toward the British throughout the next year. However, with little leadership or direction, the Indian alliances gradually broke up and, apart from scattered Indian raids and attacks, hostilities began to cease between the tribes and the British. Signs Peace Treaty At a site along the Wabash River, Pontiac finally agreed to a preliminary peace pact with the British in 1765. He also assisted the British in the peaceful subduing of several remaining rebel Indians, earning their admiration and respect by his actions. However, he embittered many of his Indian followers not only for failing to win the war but also for his benign cooperation with the enemy once peace was established. The next year, Pontiac signed a formal peace treaty at Oswego and was pardoned by the British for his involvement in the rebellion. The vanquished chief remained the target of hostile Indians in the years that followed the conflict, and in April 1769, on a trip to a trading post at Cahokia, Illinois, Pontiac was stabbed to death by Black Dog, a Peoria (Illinois) Indian. It has been speculated that Black Dog was paid by the some uneasy British officers who continued to view Pontiac's influence as a threat to their well being. Other accounts indicate that Pontiac's assassination was discussed in an Indian council and Black Dog was chosen by the council to carry out the task. Pontiac's exact burial location has never been determined. Pontiac has emerged has one of the most talented and determined Native American military tacticians who challenged and nearly halted the spread of white settlers into the American frontier. The failure of the Pontiac Rebellion of 1763 was not so much a breakdown in the tribal leader's military strategy or Indian support as it was in his ability to forge an effective alliance with the French against the British. Nevertheless, the war that Pontiac waged represents a significant milestone in European and Native American relations, for the Indians would never again have a serious opportunity to stem the tide of encroaching white settlers who took natives' land and pushed them farther and farther west. Jeffrey Amherst 1717-1797 Source:DISCovering World History. Online Detroit: Gale, 2003. From Student Resource Center - Gold. Author(s)William C. Lowe Born: January 29, 1717 in Sevenoaks, Kent, England Died: August 3, 1797 in Montreal, Kent, England Nationality: British. Occupation: Commander in chief. One of the greatest heroes of the Seven Years' War, Amherst commanded the British and colonial forces that conquered Canada from the French. Life's Work The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) marked the emergence of Amherst as a major figure in the army. At the beginning of the war, he was sent to Germany to take charge of the commissariat that supplied the mercenaries hired to protect George II's native territory of Hanover. In 1757, Cumberland arrived to take command of the Hanoverian army, and Amherst rejoined his staff. The French inflicted a major defeat on Cumberland at Hastenback (July, 1757), and he was subsequently forced into signing an embarrassing truce that George II later repudiated. Cumberland returned to England in disgrace. Amherst, however, escaped the misfortunes of his patron. In fact, his prospects improved because Ligonier replaced Cumberland as commander in chief. Though the German phase of the war continued to preoccupy the king, his ministers were more interested in eliminating France as a colonial rival, especially in North America. There the war had opened, as elsewhere, with a series of British defeats. Amherst was a key figure in the government's plans to turn the direction of the war in America. He was recalled from Germany, promoted to major general, and named to command an expedition that was being outfitted for an assault on Louisbourg. (Credit for Amherst's appointment is often given to William Pitt. It was, however, Ligonier who was primarily responsible.) Located on Cape Breton Island, Louisbourg was the largest French fortress in North America, safeguarding communications with Canada by sea. The Louisbourg expedition was Amherst's first major command, and he made the most of the opportunity. He had under him an army of about fourteen thousand and a sizable fleet under Admiral Edward Boscawen. Aided by a group of able young subordinates that included James Wolfe and William Howe, Amherst carefully cut off all avenues of escape from Louisbourg. After a siege of almost two months, the French surrendered on July 27, 1759. It was Great Britain's first major victory on land and opened one of the major routes into Canada. Elsewhere, things had not gone as well. Sir James Abercromby, attempting to invade Canada from New York by way of Lake Champlain, had been defeated by the French at Fort Ticonderoga. At the end of 1758, Amherst replaced Abercromby as commander in chief of British forces in North America. The conquest of Canada became the British government's priority for 1759. Amherst was to command, though the overall strategy was decided in London. This called for a three-pronged approach. An amphibious expedition under Wolfe and Admiral Sir Charles Saunders would sail up the St. Lawrence with Quebec as its objective. Amherst, with a large force of regulars and colonial troops, would move north from Albany along the Lake Champlain route, then link up with Wolfe on the St. Lawrence. Finally, a smaller force under Colonel John Prideaux would take Fort Niagara, cross Lake Ontario from the west, and then move down the St. Lawrence. Amherst preferred the command given to Wolfe. Ligonier, however, believed that Amherst should be with the largest force, where his prestige as commander in chief would promote greater cooperation from the colonists. The overall strategy proved successful, though Amherst had to adapt it to fit changing circumstances. In September, 1759, Wolfe won his famous victory at Quebec, though he was killed in action. Encountering much greater logistical difficulties, Amherst moved more slowly. He captured Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point and secured control of Lake Champlain, but he was unable to break through to the St. Lawrence before winter arrived. In the west, Niagara fell to the British, and the victors proceeded to extend their control over Lake Ontario. The next year, Amherst moved to complete the task that had been so well begun. Moving east from Lake Ontario, north from Lake Champlain, and west from Quebec, his forces converged on the St. Lawrence Valley. Amherst maneuvered his men skillfully and on September 8, 1760, Montreal fell with little bloodshed. Canada was now British, a state of affairs formally confirmed by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Success in Canada secured Amherst's military reputation and made him one of the war's greatest heroes in the English-speaking world. He collected a variety of rewards. In 1759, he was named royal governor of Virginia. (This was largely a sinecure worth fifteen hundred pounds a year; the governor's real duties were carried out by the lieutenant governor.) Amherst also received a vote of thanks from Parliament, and in 1761, George III made him a Knight of the Bath. In America, New England towns and a Virginia county were named for him. Amherst remained in America as commander in chief until the end of the war. With the French defeated, his main worry became relations with the Indian tribes, many of which had been French allies. Especially uncertain was the state of things in the vast transAppalachian region now passing under British control. Amherst had a decidedly negative opinion of Indians in general, and his conduct of relations with them was the least successful episode of his career. Seeing his own policy as one based on honesty and economy, Amherst ignored the advice of knowledgeable colonists, such as Sir William Johnson, and stopped a number of practices that had worked in the past, particularly the custom of giving gifts to tribes that remained peaceful. Amherst also stopped supplying the Indians with ammunition, on which many of them had come to depend for hunting. Amherst thus did little to convince many of the tribes that their interests were secure under British rule. The result was to foster discontent, which led to Pontiac's Rebellion, a largescale Indian uprising named after the famous Ottawa chief. Lasting into 1764 and spreading over much of the back country, the rebellion frustrated Amherst's attempts to put it down quickly. (At one point, he seriously considered trying to deal with unfriendly Indian tribes by sending them blankets infected with smallpox.) Amherst returned to England before the final suppression of the uprising. During the next decade, he enjoyed a relatively quiet life, though in 1768, he became involved in a dispute with the Chatham administration over its decision to send a resident governor to Virginia. Amherst did not want to go out to the colony but was offended when he was asked to resign so that someone else could be appointed. In anger, he resigned his military appointments as well. George III eventually soothed the general's wounded pride by promising him a peerage and giving him a new regiment. In 1772, Amherst returned to a more active role in military affairs when he was appointed Lieutenant General of the Ordnance. The American Revolution marked the next major phase of Amherst's career. While generally supporting the British policies that provoked the American colonists, Amherst had no desire to return to America in a military capacity. In early 1775, he turned down a request that he return as commander in chief in America. After the war broke out, Amherst gave Lord North's government the benefit of his advice. In 1776, the king kept his promise and made Amherst a peer, creating him Baron Amherst of Holmesdale. As Lord Amherst, he proved a regular attender in the House of Lords, where he continued to support the war. In 1778, however, he refused the American command for a second time. After France entered the war in 1778, Amherst became more active. He was promoted to general and named commander in chief of the army. The position was roughly analogous to a modern chief of staff, with direct command over the forces within the British Isles. It did not, however, carry great influence over the direction of the war in America. This was largely in the hands of Lord George Germain, the secretary of state for the Colonies. Amherst devoted himself to administrative matters and to preparations for home defense, for there was a real threat of a French invasion. He also took the lead in suppressing the Gordon Riots, which shook London for a week in June, 1780. With the fall of Lord North's government in 1782, Amherst's term as commander in chief came to an end. Amherst then retired to his country house (named "Montreal") in Kent. With the outbreak of war with revolutionary France in 1793, however, he returned to active duty and once again held the position of commander in chief. By this time, Amherst was seventy-six and in failing health. His return was not successful, and two years later, he resigned in favor of the king's son, Frederick, Duke of York. Amherst was compensated with promotion to field marshal, the highest rank in the British army. Amherst's last retirement was relatively brief: He died on August 3, 1797. Summary Apart from his subordinate, James Wolfe, Jeffrey Lord Amherst was the best-known British general of the Seven Years' War and arguably the most successful. The conquest of Canada was his most notable achievement, and he has traditionally been regarded as one of the founding fathers of English Canada. The campaign may have taken longer than originally intended, but Amherst's careful and professional approach minimized the risks in a situation where defeat would have had disastrous consequences. Amherst also, by his development of light infantry tactics, did much to adapt the British army to North American conditions. Subsequent phases of Amherst's career were less dramatic, though not without importance. His insensitive approach to Indian relations helped to bring on Pontiac's Rebellion, an event that contributed to the British resolve to maintain an army in America after 1763. This policy was, in turn, a factor in promoting the British to look for new sources of revenue in the Colonies. The measures that resulted eventually led to the American Revolution. During the period of growing strife with the Americans, Amherst was often sought out by the king and cabinet because of his knowledge of American conditions. He gave advice, joined the cabinet (as commander in chief), and did much to prepare Great Britain for a threatened invasion. After the British defeat at Saratoga in 1777, Amherst was one of the first to realize that Great Britain lacked the military resources to continue an offensive war in America. His advice in favor of a more defensive, naval-oriented strategy, however, was not taken. In the end, Amherst witnessed, as commander in chief, the reduction of an American empire he had done much to expand. PROCLAMATION OF 1763 Source:Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Eds. Thomas Carson and Mary Bonk. Vol. 2. p820821. (816 words) From Gale Virtual Reference Library. Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group, COPYRIGHT 2005 Thomson Gale, a part of the Thomson Corporation The British government intended the Proclamation of 1763 partly as a war measure and partly as a means of administering the new territory taken from France under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. It had two main provisions that affected the colonists. First, the British government drew a line along the watershed of the Appalachian Mountains—the point at which waters run downhill either to the Atlantic Ocean in the east or to the Mississippi River drainage system in the west—separating colonial territory from that of the Native Americans. All lands west of the line were reserved exclusively for Indians, and any settlers living in Indian territory were required to leave. Secondly, in order to make certain that peace was maintained on the American frontier, the British government arranged for the garrisoning of up to 10,000 soldiers in the colonies. The cost of their upkeep, British Prime Minister George Grenville decided, would be borne by the colonists— an estimated 250,000 pounds sterling per year. Although some members of the British government may have had a sincere desire to protect the land rights of Native Americans, their main intention was to evade more expensive Indian wars. By limiting white settlement to areas east of the Appalachian watershed, the government hoped to minimize conflict between Indians and colonists. However, Grenville's government also wanted to tie the American colonies closer to England. The British worried that settlers who moved to lands across the Appalachians and lost direct contact. The Proclamation of 1763 was issued by the British to segregate colonists and Indians. The colonists were to stay east of the Appalachian Mountains, and Indians to the west, thus avoiding Indian conflicts, and continued British control of the colonists, with the British Empire would form economic ties with the Mississippi Valley, then under Spanish control. They also realized that these settlers would need to manufacture some goods for themselves, rather than importing them from England. The British feared that in time such local industries would undercut imperial trade. The simplest way to prevent these things from happening was to forbid settlement west of the Appalachians. This would also keep colonial settlers from drifting away from a market economy. A settler who went far into the interior and began to live in a subsistent economy without using money, would soon lose contact with other colonists and, eventually, also his allegiance to the British crown. The second part of the Proclamation also threatened American economic prosperity. Grenville's government had inherited a national debt of 137 million pounds sterling, almost twice what it had been before the beginning of the war with France. The costs of administering the North American empire, Grenville concluded, could well be borne by the colonists, whose debt amounted to only 2.6 million pounds sterling. But the colonies were suffering from a severe post-war depression, and hard cash, or specie (minted gold and silver), was in short supply because of the colonial trade deficit with Great Britain. Most colonial specie was used to pay English or Scottish merchants for goods the colonists had imported. In order to raise the 250,000 pounds sterling needed to fund the frontier troops, Grenville's government put together a series of direct and indirect taxes on colonial goods and services, including the Sugar Act, the Currency Act, and the Stamp Act. These taxes led to conflict between the American colonies and England, eventually culminating in the American Revolution (1775– 1783).