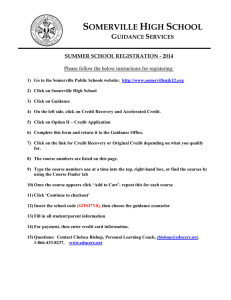

magazine - Somerville College

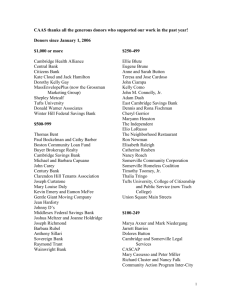

advertisement