Collection 2

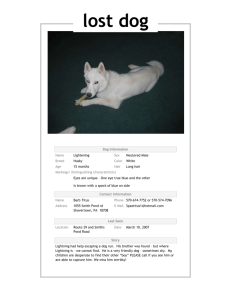

advertisement