Attitude toward ethical behavior in computer use: a shifting model

advertisement

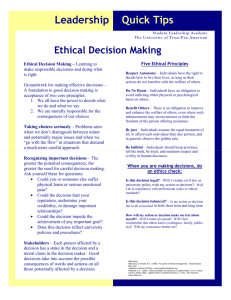

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0263-5577.htm IMDS 105,9 Attitude toward ethical behavior in computer use: a shifting model 1150 University of Tulsa, Management Information Systems Department, College of Business Administration, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, and Lori N.K. Leonard Timothy Paul Cronan University of Arkansas, Information Systems Department, Walton College of Business, Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA Abstract Purpose – In this study the researchers attempt to identify factors that could influence an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior in the information systems (IS) environment and compare them to the findings of an earlier study to determine any changes. Design/methodology/approach – A sample of university students is used to assess environmental influences (societal, belief system, personal, professional, legal, and business), moral obligation, consequences of the action, and gender, in order to determine what influences an individual’s attitude toward a behavior. Discriminant analysis is used to assess the factor influences. Findings – The findings indicate that many factors influence attitude toward ethical decisions and are dependent upon the type of ethical issue involved. Moreover, based on two time periods, the ethical attitude influencers have shifted over time. The gender findings indicate that attitude influencers are also dependent on the sex of the individual. Originality/value – The findings show that attitude influencers have shifted over time (since an earlier study), which means that organizations must periodically reassess their employees’ ethical climate and adjust their ethics’ programs as attitude influencers change. The findings also show that training programs need to focus on the different influencers for males and females. Keywords Ethics, Attitudes, Behaviour, User studies, Information systems Paper type Research paper Industrial Management & Data Systems Vol. 105 No. 9, 2005 pp. 1150-1171 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0263-5577 DOI 10.1108/02635570510633239 Introduction The misuse of and unethical behavior toward information systems (IS) have caused significant losses to businesses and society. Organizations have invested in the development and implementation of security measures, but computer misuse continues to be a problem. Monetary loss through unethical and criminal use of computers is estimated to be billions of dollars per year (Haugen and Selin, 1999; Hubbard and Forcht, 1998; Marshall, 1999; McCollum, 2004; Parks, 2005; Power, 2000; Trembly, 1999). Unacceptable, illegal, and/or unethical use of computers are concerns to IS professionals because of the potential harm to society and to the integrity of the IS profession. Therefore, research support has increased for studying the ethical attitudes of personnel, deterrents to unethical behavior, the various types of unethical behavior, and approaches to teaching ethics in the field of MIS (Aiken, 1988; Bowie, 2005; Conner and Rumelt, 1991; Cougar, 1989; Foltz et al., 2005; Heide and Hightower, 1988; Leonard et al., 2004; Oz, 1990; Paradice, 1990; Saari, 1987; Straub and Nance, 1990; Steinke and Nickolette, 2003; Zalud, 1984). Attitude has been found to significantly affect an individual’s intention to behave ethically or unethically (Ajzen, 1989, 1991; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1969, 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Leonard and Cronan, 2001). Therefore, understanding the dimensions of attitude will lead to the further understanding of the influences on ethical behavior intention. Society has changed significantly since Kreie and Cronan (1999) explored an attitudinal model – even wider use of the internet, more identity theft, digital privacy, etc. Given these changes, the dimensions of attitude are also expected to change. Moreover, gender was not considered in Kreie and Cronan’s study; however, many research studies have found a person’s gender to play a role in explaining ethical behavioral attitude and intention (Banerjee et al., 1996; Gattiker and Kelley, 1999; Deshpande, 1997; Leonard and Cronan, 2001; Leonard et al., 2004). Therefore, the purpose of the present study is to identify the influences on an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior and to compare those influences to the findings of an earlier study, as well as to determine the role of gender in attitude differences. Respondents were presented with five IS dilemmas and an action and asked to indicate the probability that they agreed with the action. Then, they are asked to indicate the degree to which various factors influenced their attitude (toward ethical behavior) for each scenario. Attitude toward ethical behavior model Attitude toward ethical behavior is an individual’s degree of favorable or unfavorable evaluation of a behavior. Bommer et al. (1987) proposed an ethical decision-making model with several environmental factors that could explain general ethical behavior (i.e. an individual’s attitude toward the behavior). The environmental influences are societal, belief system, personal, professional, legal, and business. The societal environment captures the social and cultural values that impact the individual (Ferrell and Gresham, 1985). One’s belief system consists of religious values and beliefs developed in an individual’s spiritual or religious environment. Personal values are an individual’s personal goals, experiences, and moral level, and personal environment is the influence of family, peers, and significant others (Ferrell and Gresham, 1985). Professional environment consists of the codes of conduct and professional expectations of an individual’s profession (Higgs-Kleyn and Kapelianis, 1999). Legal environment captures the law, the legislation, and the government, which may persuade individuals to refrain from some prohibited behavior. Business environment consists of corporate goals and profit motive of the company in which the individual works. A company’s stated policies may increase the probability of ethical behavior (Trevino, 1986; Victor and Cullen, 1988). In addition to an individual’s environmental influences, moral obligation and potential (perceived) consequences of one’s behavior have been shown to influence an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior. Personal normative beliefs entails the moral obligation an individual feels to perform or not to perform a behavior (Schwartz and Tessler, 1972). Consequences capture an individual’s awareness that unethical behavior may have a penalty that affects the decision maker and/or others. When examining software piracy, Eining and Christensen (1991) reported that consequences were a significant influence on an individual’s behavioral intention. Kreie and Cronan (1998) also found that consequences influence ethical decision-making. In 1999, Kreie and Cronan proposed an end-user computing model for an ethical dilemma. Their model studied the influence of societal environment, belief system, A shifting model 1151 IMDS 105,9 1152 Figure 1. Attitude toward ethical behavior of information systems personnel personal values, personal environment, professional environment, legal environment, business environment, moral obligation, and awareness of consequences on an individual’s decision as to the behavior, in each case, being acceptable (ethical) or unacceptable (unethical). After assessing five cases using student subjects (from computing classes at a Midwestern university in the United States), they found four of the five cases to be considered unacceptable, with moral obligation being a significant influence in all cases. Ultimately, the study showed that influencing factors differ by case (i.e. situation). Based on the Kreie and Cronan (1999) attitudinal model (Figure 1), the attitude model in the present study indicates that an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior is influenced by several factors from the decision maker’s environment (societal, belief system, personal, professional, legal and business), moral obligation and the possible consequences of a behavior. These factors were originally identified by Bommer et al. (1987)) in a model of ethical decision-making. However, the factors were never empirically tested. Ethical attitude has the propensity to change as society changes. Privacy is an issue that is continually being discussed in the media. Computer security, or lack thereof, and identity theft are also discussed on a regular basis. Therefore, most individuals would have exposure to these issues over time, whereas in 1999 (when the Kreie and Cronan study was published), students would have had considerably less exposure to these important issues since they were not discussed much in the media or the classroom. Another issue more prevalent today is downloading music and movies from the internet-piracy. Since many people downloaded music from Napster freely prior to regulation and routinely copy movies and DVDs, those same people may have the attitude that that behavior is acceptable practice and that the music/movies/DVDs should be free regardless of the laws that govern it. Therefore, it is advantageous to explore if attitude influencers may have changed over time. Consequently, there is a need to reassess attitude influencers with a new sample from the same type of population to see if the influencers proposed have changed over time. There has been mixed research regarding gender as an indicator of ethical/unethical behavioral intention. Yet, many researchers have found gender to influence ethical behavior and attitude (Banerjee et al., 1996; Gattiker and Kelley, 1999; Deshpande, 1997; Kreie and Cronan, 1998; Leonard and Cronan, 2001; Leonard et al., 2004) with women tending to judge questionable behavior as less ethical and indicating that they would be less likely to engage in this behavior than men. Venkatesh et al. (2000) sought to understand technology adoption and usage decisions by focusing on differences in the decision-making process of men and women. They found: . attitude to influence behavioral intention for men more than women; . subjective norm to influence behavioral intention for women more than men; and . perceived behavioral control to influence behavioral intention for women more than men. Venkatesh and Morris (2000) also found behavioral intention to be influenced by usefulness for men and ease of use for women, and subjective norm to influence behavioral intention more strongly for women. There is also evidence to suggest that men and women’s ethical decision-making process is different. Loch and Conger (1996) found men to rely on their attitudes toward an action when deciding to perform a computing act, whereas women rely on prevailing social norms. Dawson (1997) also found women to reach ethical judgments based on relationships rather than rights and rules. Therefore, it is important that gender differences will also be included in this study. Research model A representation of the attitude toward ethical decision model for this study is: ATT ¼ f ðSOC; BEL; PVAL; PE; PRF; LGL; BUS; MO; CONÞ where ATT ¼ Attitude toward ethical behavior – an individual’s degree of favorable/unfavorable evaluation of the behavior in question. SOC ¼ Societal environment – society’s values; an individual’s culture (Bommer et al., 1987). BEL ¼ Belief system – religious values and beliefs (Bommer et al., 1987). A shifting model 1153 IMDS 105,9 1154 PVAL ¼ Personal values – an individual’s personal values, goals, and experiences (Bommer et al., 1987). PE ¼ Personal environment – the influence of family, peers and significant others (Bommer et al., 1987; Ferrell and Gresham, 1985). PRF ¼ Professional environment – codes of conduct and professional expectations within an individual’s profession (Bommer et al., 1987; Higgs-Kleyn and Kapelianis, 1999). LGL ¼ Legal environment – law, legislation, and government (Bommer et al., 1987). BUS ¼ Business environment – corporate goals and profit motive (Bommer et al., 1987; Trevino, 1986; Victor and Cullen, 1988). MO ¼ Moral obligation – personal normative beliefs (Schwartz and Tessler, 1972). CON ¼ Consequences – awareness that behavior may have consequences that affect oneself and/or others (Bommer et al., 1987; Eining and Christensen, 1991; Rest, 1979). Method The ethical attitudinal model (1) hypothesizes that attitude is influenced by the decision maker’s environmental factors, moral obligation, and possible consequences of behaving one way or another. To measure the possible influential factors, a survey instrument was used. The survey contains five computing cases (the same cases used by Kreie and Cronan (1999) were used in order to justify a shifting attitudes model) and captures the respondent’s attitude toward the behavior of the person described in a case. The cases present situations involving ethical issues such as individual privacy, data accuracy, and intellectual property – issues described by Mason (1986). The cases used in the instrument are given in the Appendix. Kreie and Cronan’s (1999) eight items on a five-point scale are used to measure the influencers of attitude. Multiple discriminant analysis is used to determine the effects of each factor on the acceptable/unacceptable ethical decision. Stepwise discriminant analysis is used to determine the significant factors that discriminate between the attitudes. Sample To be able to compare results of the present study with those of Kreie and Cronan, questionnaire respondents were students[1] in computing classes at a Midwestern university in the US (as were Kreie and Cronan’s respondents). Four hundred and twenty-two (422)[2] survey responses were received. The sample consists of 48.3 percent female (51.7 percent male) respondents. The respondents’ ages range from 18 to 54 years, with an average of 21.9 years. The average GPA is 2.8 (ranging from 1.0 to 4.0), the average work experience for these students is 1.1 years (ranging from 0 to 6 years), and over half of the respondents (54.7 percent) are juniors and seniors. The sample is comparable to that used by Kreie and Cronan (1999). Results Table I presents a summary of the attitude toward the behavior and the factors theorized to influence the individual’s attitude toward the situation. For each case, respondents indicated the degree of influence each environmental factor had in assessing whether the person’s behavior was acceptable or not (influence rated from “none” to “great”). Respondents also indicated whether the actor in the case should have acted as described, given certain consequences for such behavior. For cases A, B, D and E, respondents viewed the behavior in question to be unacceptable (i.e. unethical). In case C, respondents thought the behavior was acceptable (i.e. ethical). When compared to Kreie and Cronan (1999), our study shows that the case perceptions (acceptable or unacceptable) have not changed. Kreie and Cronan found cases A, B, D and E to be unacceptable and case C to be acceptable. In case A, for instance, which describes a programmer who manipulates a bank’s accounting system to hide his overdrawn account, the frequencies in Table I indicate that 83.8 percent of the respondents view modifying the program as unacceptable. Over 80 percent of the respondents said their personal values were very influential (influence rated as “much” or “great”). Belief system, moral obligation and consequences were also influential. A general model is developed using multiple discriminant analysis. To increase the power of the statistical tests, the 10 percent significance level ða ¼ 0:10Þ is used. The attitude model tests the importance of each of the independent influences on the measure of attitude toward the ethical behavior in question. Table II presents the discriminant analysis results of the attitude model and classification values. Models are developed for each of the five cases. Overall, moral obligation appears to influence attitude in all five cases, and consequences is an influence in four of the five cases and belief system in three of the five cases. As in the Kreie and Cronan (1999) work, classification rates for the full model are listed as well as classification rates for the reduced (significant) models. Moral obligation, consequences, belief system, and personal values are found to be influences on attitude (toward ethical behavior) in case A with a classification rate of 77.3 percent; moral obligation, consequences, belief system, and business environment in case B with a classification rate of 76.4 percent; moral obligation, personal environment, and consequences in case C with a classification rate of 75.8 percent; moral obligation, consequences, and belief system in case D with a classification rate of 68.2 percent; and moral obligation and personal values in case E with a classification rate of 72.2 percent. Table III provides a comparison of the current study findings to Kreie and Cronan’s (1999) findings. Both studies found moral obligation to be a significant influence on attitude. The current study found consequences to be an influence in four of the five cases and belief system in three of the five cases. In the Kreie and Cronan study, legal environment was important in four of the five cases, but it was not significant in any of the cases in the current study. Noting some differences in each ethical situation (case), we further the attitude toward ethical behavior research by assessing attitude influencers for each case given the respondent’s gender. Table IV presents a summary of the attitude toward the behavior and the factors theorized to influence the individual’s (male or female) attitude toward the situation for those who decided the behavior was unacceptable. Table V presents the same information (male or female) for those who decided the behavior was acceptable. A shifting model 1155 Table I. Factors and percent weights used for ethical decisions Decision N Percent Variable Societal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Belief system None Little Moderate Much Great Personal values None Little Moderate Much Great Personal environment None Little Moderate Much Frequencies 1156 336 83.8 6.2 12.1 32.7 32.7 16.5 9.1 12.6 17.0 22.3 39.0 5.9 3.3 6.8 25.6 58.5 4.4 9.4 24.9 25.8 65 16.2 13.6 15.2 37.9 15.2 18.2 19.7 16.7 24.2 22.7 16.7 3.0 1.5 9.1 34.9 51.5 6.2 13.9 30.8 24.6 6.8 17.0 36.7 24.5 2.0 8.8 21.1 39.5 28.6 14.4 15.8 27.4 28.1 14.4 11.6 17.7 30.6 25.9 14.3 146 36.7 3.6 11.9 28.9 25.3 4.3 4.7 10.6 28.4 52.0 5.5 11.8 20.1 23.6 40.0 6.3 18.1 26.4 31.1 18.1 252 66.3 10.8 15.1 31.8 25.3 5.9 11.5 24.9 29.8 27.9 15.4 19.7 27.2 23.6 14.1 14.1 17.4 36.7 21.0 10.9 304 78.0 2.3 8.1 26.4 26.4 2.3 8.1 8.1 36.1 45.4 8.1 11.5 24.1 25.3 31.0 6.9 12.6 32.2 23.0 25.3 86 22.0 7.9 15.8 39.6 23.8 5.9 5.9 30.7 32.7 24.8 20.6 11.8 38.2 21.6 7.8 16.7 7.8 39.2 23.5 12.8 99 26.3 5.4 10.8 30.5 29.0 2.5 7.9 17.6 28.8 43.2 9.3 11.5 24.0 24.4 30.8 5.0 11.2 34.5 33.5 15.8 277 73.7 7.8 8.7 43.5 19.1 3.5 9.5 30.2 28.5 28.5 13.8 12.9 33.6 20.7 19.0 6.9 13.8 37.1 22.4 19.8 116 30.5 5.3 10.2 20.7 29.3 (continued) 3.4 5.2 9.0 29.6 52.8 8.2 9.0 16.9 28.1 37.8 4.1 7.9 18.0 39.0 31.1 265 69.5 Case A (programmer Case C (company Case D (used program Case E (copied data made manipulates accounting Case B (software sent in equipment used on without paying required accessible during contract system) error was kept) personal time) fee) work) Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable IMDS 105,9 Great Professional environment None Little Moderate Much Great Legal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Business environment None Little Moderate Much Great Frequencies 35.5 5.0 9.7 11.5 25.3 48.5 7.9 9.1 21.2 23.2 38.5 6.5 12.9 18.8 27.9 34.0 24.6 6.1 12.1 22.7 27.3 31.8 6.1 13.6 21.2 28.8 30.3 7.7 7.7 27.7 35.4 21.5 6.8 12.9 31.3 28.6 20.4 8.2 16.3 34.0 27.2 14.3 6.2 17.2 28.3 28.3 20.0 15.0 8.3 13.4 28.0 28.0 22.4 6.7 14.6 22.4 31.1 25.2 5.9 11.4 23.6 29.1 29.9 30.4 9.2 12.4 30.1 25.8 22.6 14.1 19.3 24.8 25.2 16.7 4.9 8.5 26.8 32.7 27.1 17.1 8.1 8.1 17.2 26.4 40.2 9.2 17.2 16.1 32.2 25.3 4.6 8.1 21.8 25.3 40.2 36.8 6.9 10.8 25.5 38.2 18.6 10.8 10.8 33.3 28.4 16.7 2.0 7.9 28.7 35.6 25.7 12.9 5.4 6.8 24.7 29.8 33.3 5.7 7.5 22.2 31.9 32.6 4.3 5.0 20.4 29.4 40.9 24.4 34.6 4.5 7.1 15.0 29.2 44.2 6.7 9.4 17.2 26.2 40.5 7.1 9.7 18.7 27.0 37.5 (continued) 20.9 3.5 10.3 18.1 42.2 25.9 3.5 12.9 29.3 34.5 19.8 5.2 12.1 23.3 25.9 33.6 Case A (programmer Case C (company Case D (used program Case E (copied data made manipulates accounting Case B (software sent in equipment used on without paying required accessible during contract system) error was kept) personal time) fee) work) Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable A shifting model 1157 Table I. Table I. 5.8 13.8 27.6 23.0 30.0 – 4.6 5.8 25.3 64.4 45.5 25.3 19.2 7.8 2.3 4.2 3.9 13.6 19.8 58.4 9.9 16.8 18.8 15.8 38.6 21.0 24.0 35.0 17.0 3.0 1.8 3.6 13.6 22.2 58.8 4.3 11.5 29.0 31.5 23.7 4.2 7.5 24.2 15.0 49.2 15.0 24.2 35.8 14.2 10.8 2.3 1.9 9.7 16.9 69.3 1.9 6.0 21.1 25.9 45.1 Notes: A dash ( –) represents a zero weight; variables whose frequencies are in italics were determined to be significant variables based on stepwise discriminant analysis; athe actual wording regarding awareness of consequences varied based on the scenario The following two items were scored on a 5-point scale with two anchors Moral obligation No obligation 24.6 3.8 36.7 6.2 No obligation 30.8 10.0 33.3 12.8 No obligation 21.5 15.0 21.8 32.7 No obligation 13.9 32.8 6.1 24.1 Strong obligation 9.2 38.1 2.0 24.1 Awareness of consequences a Should have 10.8 3.0 17.0 5.1 Should have 9.2 3.0 12.9 4.7 Should have 20.0 5.6 14.3 11.8 Should have 29.2 13.3 20.4 19.2 Should not have 30.8 74.9 35.4 59.2 Frequencies 1158 Case A (programmer Case C (company Case D (used program Case E (copied data made manipulates accounting Case B (software sent in equipment used on without paying required accessible during contract system) error was kept) personal time) fee) work) Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable IMDS 105,9 Predicted Case A a Moral obligation Awareness of consequences Belief systems Personal values Case B a Moral obligation Awareness of consequences Belief system Business environment Case C a Moral obligation Personal environment Awareness of consequences Case D a Moral obligation Awareness of consequences Belief system Case E a Moral obligation Personal values Unacceptable Acceptable Total Unacceptable 260 76 336 Acceptable Total 15 275 50 126 65 401 Unacceptable 192 60 252 Acceptable Total 34 226 112 172 146 398 65 72 21 232 86 304 Total 137 253 390 Unacceptable 193 84 277 Acceptable Total 33 226 66 150 Unacceptable Acceptable Total 184 25 209 81 91 172 Unacceptable Acceptable Model classification rate Reduced (significant) Full (percent) (percent) A shifting model 1159 77.3 78.1 76.4 77.0 75.8 77.4 99 376 68.2 69.3 265 116 381 72.2 74.7 Note: aFactors listed were significant variables in the reduced model It is noted that females viewed the behavior in question to be more unacceptable (i.e. unethical) than did males (Table IV), and that males view the behavior in question to be more acceptable (i.e. ethical) than females (Table V). For example, in case A (which describes a programmer who manipulates a bank’s accounting system to hide his overdrawn account), the frequencies in Tables IV and V indicate that of the 334 responses classified as unacceptable, 50.3 percent are females and 49.7 percent are males, and of the 65 responses classified as acceptable, 29.2 percent are females and 70.8 percent are males. Table VI summarizes the acceptable/unacceptable decisions by case for both males and females. Two general models are developed (males and females) using discriminant analysis. To increase the power of the statistical tests, the 10 percent significance level ða ¼ 0:10Þ is used. Table VII presents the discriminant analysis results of the attitude model and classification values for females and males for each of the five cases. For the females, generally moral obligation appears to influence attitude in all five cases, and many other environmental factors influence attitude depending on the case in question. Moral obligation, consequences, and societal environment are found to be influences on attitude (toward ethical behavior) in case A with a Table II. Classification rates for factors used IMDS 105,9 Current study Case A 1160 Case B Case C Case D Table III. Comparison of studies for attitude influence Case E Model classification rate (percent correctly classified) Kreie and Cronan (1999) Moral obligation Consequences Belief system Personal values Moral obligation Consequences Belief system Business environment 77.3 Moral obligation Personal environment Consequences Moral obligation Conseqeunces Belief system 75.8 68.2 Moral obligation Legal environment 66.9 Moral obligation Personal values 72.2 Moral obligation Consequences Legal environment 74.8 76.4 Moral obligation Consequences Belief system Legal environment Moral obligation Consequences Personal values Societal environment Legal environment Moral obligation Model classification rate (percent correctly classified) 77.6 73.1 75.3 classification rate of 77.5 percent; moral obligation, belief system, and professional environment in case B with a classification rate of 80.2 percent; moral obligation and personal environment in case C with a classification rate of 78.9 percent; moral obligation, belief system, personal values, personal environment, and legal environment in case D with a classification rate of 76.4 percent; and moral obligation, societal environment, and business environment in case E with a classification rate of 76.7 percent. Overall for the males, moral obligation appears to influence attitude in all five cases, and consequences and personal values are influences in four of the five cases. Moral obligation, consequences, belief system, and legal environment are found to be influences on attitude (toward ethical behavior) in case A with a classification rate of 79.3 percent; moral obligation, consequences, personal values, societal environment, and belief system in case B with a classification rate of 75.7 percent; moral obligation, personal values, business environment, and consequences in case C with a classification rate of 74.8 percent; moral obligation, consequences, personal values, professional environment, and societal environment in case D with a classification rate of 70.6 percent; and moral obligation and personal values in case E with a classification rate of 69.7 percent. Comparing the findings for females and males, moral obligation is a significant influence on attitude for both. However, males also use personal values and their awareness of consequences when assessing a behavior. Females have different variables influencing attitude depending on the situation in question. There is no consistency in the case assessments by females other than the influence of moral obligation. Decision N Percent Variable Societal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Belief system None Little Moderate Much Great Personal values None Little Moderate Much Great Personal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Professional environment None Little Moderate Much Frequencies 166 49.7 7.1 13.0 32.5 31.4 16.0 11.2 13.6 18.9 26.6 29.6 6.6 4.2 8.3 28.6 52.4 4.1 11.2 26.6 29.0 29.0 7.1 10.7 14.9 22.6 168 50.3 5.3 11.2 32.9 34.1 16.5 7.0 11.7 15.2 18.1 48.0 5.3 2.3 5.3 22.2 64.9 4.7 7.6 22.8 22.8 42.1 2.9 8.8 8.1 27.5 Case A (programmer manipulates accounting system) Females Males 5.3 7.5 21.8 25.6 3.0 9.1 28.8 22.0 37.1 3.8 5.3 10.5 25.6 54.9 3.0 10.5 23.3 20.3 42.9 5.3 16.5 23.2 33.8 21.1 133 52.8 6.6 15.7 25.6 33.1 4.1 14.9 28.9 28.9 23.1 5.0 4.1 10.7 31.4 48.8 8.3 13.2 16.5 27.3 34.7 7.4 19.8 29.8 28.1 14.9 119 47.2 Case B (software sent in error was kept) Females Males 2.1 8.5 17.0 19.2 4.3 4.3 19.2 23.4 48.9 – 10.6 6.4 31.9 51.1 6.4 17.0 23.4 19.2 34.0 4.2 14.9 34.0 19.2 27.7 47 55.3 7.5 7.5 27.5 32.5 – 12.5 35.0 30.0 22.5 5.1 5.1 10.3 41.0 38.5 10.0 5.0 25.0 32.5 27.5 10.0 10.0 30.0 27.5 22.5 38 44.7 Case C (company equipment used on personal time) Females Males 2.7 4.8 16.4 25.3 2.1 10.3 31.5 26.7 29.5 2.7 6.1 15.8 25.3 50.0 5.5 11.6 24.7 24.7 33.6 3.5 10.3 31.7 35.9 18.6 146 52.9 6.0 5.3 24.8 33.8 9.0 11.3 29.3 31.6 18.8 2.3 9.9 19.7 32.6 35.6 13.5 11.3 23.3 24.1 27.8 6.8 12.0 37.6 30.8 12.8 130 47.1 Case D (used program without paying required fee) Females Males 137 51.7 5.8 7.9 21.6 41.0 23.7 12.2 8.6 17.3 33.1 28.8 5.0 5.8 10.1 32.4 46.8 7.3 11.6 23.9 28.3 29.0 6.5 7.2 16.6 33.8 (continued) 128 48.3 2.3 7.8 14.1 36.7 39.1 3.9 9.4 16.4 22.7 47.7 1.6 4.7 7.8 26.6 59.4 3.1 8.6 17.2 30.5 40.6 2.3 7.0 13.3 24.2 Case E (copied data made accessible during contract work) Females Males A shifting model 1161 Table IV. Factors and percent weights used for unacceptable decisions Table IV. 53.2 6.4 19.2 19.2 25.5 29.8 2.1 8.5 14.9 25.5 48.9 6.3 14.6 27.1 27.1 25.0 – – 4.2 27.1 68.8 19.0 6.6 19.8 26.5 30.6 16.5 6.6 15.7 31.4 30.6 15.7 5.8 13.2 29.8 29.8 21.5 5.0 5.9 16.0 21.9 51.3 – 10.3 7.7 23.1 59.0 5.1 12.8 28.2 17.9 35.9 15.0 7.5 20.0 27.5 30.0 12.5 15.0 12.5 40.0 20.0 25.0 Case C (company equipment used on personal time) Females Males 2.7 4.1 6.8 20.3 66.2 4.7 11.5 28.4 30.4 25.0 4.1 4.1 21.9 28.1 41.8 2.1 8.2 21.2 30.8 37.7 50.7 0.8 3.1 21.4 24.4 50.4 3.8 11.5 29.8 32.8 22.1 6.8 9.8 27.8 31.6 24.1 9.8 6.8 23.3 33.1 27.1 30.1 Case D (used program without paying required fee) Females Males 2.3 0.8 6.2 10.9 79.8 3.1 5.4 16.3 31.0 44.2 6.3 9.4 15.6 27.3 41.4 3.1 9.4 16.4 21.1 50.0 53.1 2.2 2.9 13.0 22.5 59.4 0.7 6.6 25.6 21.2 46.0 7.9 10.1 21.6 26.6 33.8 10.1 9.4 18.0 30.9 31.7 36.0 Case E (copied data made accessible during contract work) Females Males Notes: A dash ( –) represents a zero weight; variables whose frequencies are in italics were determined to be significant variables based on stepwise discriminant analysis; athe actual wording regarding awareness of consequences varied based on the scenario Great 52.3 44.6 39.9 Legal environment None 5.9 10.1 6.8 Little 7.6 10.7 9.8 Moderate 17.5 25.0 18.8 Much 24.6 21.4 31.6 Great 44.4 32.7 33.1 Business environment None 7.0 5.9 9.8 Little 9.9 16.0 11.3 Moderate 17.0 20.7 24.8 Much 28.1 27.2 25.6 Great 38.0 30.2 28.6 The following two items were scored on a 5-point scale with two anchors Moral obligation No obligation 4.7 2.3 6.6 No obligation 9.9 10.1 12.5 No obligation 13.4 16.1 35.3 No obligation 32.6 33.3 19.1 Strong obligation 39.5 36.9 26.5 a Awareness of consequences Should have 3.5 2.4 5.2 Should have 4.1 1.8 3.7 Should have 2.3 8.4 8.1 Should have 9.4 17.4 16.9 Should not have 80.7 69.5 66.2 Case B (software sent in error was kept) Females Males 1162 Frequencies Case A (programmer manipulates accounting system) Females Males IMDS 105,9 Decision N Percent Variable Societal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Belief system None Little Moderate Much Great Personal values None Little Moderate Much Great Personal environment None Little Moderate Much Great Professional environment None Little Moderate Frequencies 46 70.8 19.6 17.4 37.0 15.2 10.9 21.7 19.6 26.1 21.7 10.9 4.4 2.2 10.9 34.8 47.8 8.9 17.8 26.7 26.7 20.0 8.7 13.0 23.9 19 29.2 – 10.0 40.0 15.0 35.0 15.0 10.0 20.0 25.0 30.0 – – 5.0 35.0 60.0 – 5.0 40.0 20.0 35.0 – 10.0 20.0 Case A (programmer manipulates accounting system) Females Males 3.7 7.4 27.8 3.7 14.8 31.5 31.5 18.5 – 3.7 24.1 39.9 33.3 9.3 24.1 22.2 25.9 18.5 3.7 20.4 35.2 25.9 14.8 54 37.2 7.8 23.3 28.9 8.7 18.5 40.2 19.6 13.0 3.3 12.0 19.6 39.1 26.1 17.6 11.0 30.8 29.7 11.0 16.3 16.3 27.2 26.1 14.1 91 62.8 Case B (software sent in error was kept) Females Males 4.3 4.3 28.1 9.4 16.6 30.2 25.9 18.0 5.0 10.1 25.9 27.3 31.7 11.5 25.9 22.3 23.7 16.6 13.0 20.9 36.7 20.7 8.6 138 45.5 5.4 12.1 25.9 12.1 13.3 33.3 24.9 16.4 6.7 12.7 24.2 31.5 24.9 18.8 14.6 31.5 23.0 12.1 15.2 14.6 37.0 20.6 12.7 165 54.5 Case C (company equipment used on personal time) Females Males – 11.8 23.5 11.8 11.8 44.1 26.5 5.9 2.9 2.9 29.4 29.4 35.3 29.4 2.9 38.2 20.6 8.8 20.6 14.7 29.4 20.6 14.7 32 33.3 3.0 6.1 31.8 6.1 18.2 36.4 22.7 16.7 7.6 7.6 31.8 33.3 19.7 16.4 16.4 38.8 20.9 7.5 14.9 4.5 44.8 23.9 11.9 64 66.7 Case D (used program without paying required fee) Females Males 64 55.2 4.7 17.2 35.9 20.3 21.9 17.2 15.6 29.7 21.9 15.6 3.1 9.4 37.5 26.6 23.4 7.9 12.7 42.9 15.9 20.6 3.1 15.6 21.9 (continued) 52 44.8 9.6 9.6 38.5 25.0 17.3 9.6 9.6 38.5 19.2 23.1 3.9 9.6 21.2 30.8 34.6 7.7 3.9 44.2 23.1 21.2 3.9 3.9 13.5 Case E (copied data made accessible during contract work) Females Males A shifting model 1163 Table V. Factors and percent weights used for acceptable decisions Table V. 31.7 31.7 13.7 17.3 22.3 26.6 20.1 8.6 15.1 28.8 22.3 25.2 45.0 27.1 20.0 5.7 2.1 2.1 3.6 7.9 20.0 66.4 25.6 14.4 9.8 14.1 33.7 29.4 13.0 7.6 15.2 30.4 26.1 20.7 37.0 29.4 25.0 6.5 2.2 22.8 13.0 14.1 20.7 29.4 6.0 4.2 18.0 19.8 52.1 45.5 24.0 18.6 9.6 2.4 9.6 10.2 30.7 28.9 20.5 14.5 20.5 27.1 24.1 13.9 33.1 23.5 Case C (company equipment used on personal time) Females Males 6.3 9.4 6.3 15.6 62.5 15.6 34.4 25.0 25.0 – 8.8 14.7 29.4 26.5 20.6 14.7 11.8 32.4 17.7 23.5 38.2 26.5 11.8 20.6 23.5 16.2 27.9 23.9 19.4 38.8 13.4 4.5 6.0 9.0 23.9 44.8 16.4 9.0 10.5 32.8 34.3 13.4 34.9 24.2 Case D (used program without paying required fee) Females Males – 9.1 14.6 14.6 61.8 14.6 30.9 27.3 10.9 16.4 3.9 11.5 15.4 28.9 40.4 3.9 9.6 25.0 36.5 25.0 42.3 36.5 7.7 6.2 32.3 15.4 38.5 15.4 18.5 43.1 16.9 6.2 6.3 12.5 29.7 23.4 28.1 3.1 15.6 32.8 32.8 15.6 42.2 17.2 Case E (copied data made accessible during contract work) Females Males Notes: A dash ( –) represents a zero weight; variables whose frequencies are in italics were determined to be significant variables based on stepwise discriminant analysis; athe actual wording regarding awareness of consequences varied based on the scenario Much 30.0 26.1 31.5 Great 40.0 28.3 29.6 Legal environment None – 8.7 5.6 Little 20.0 10.9 20.4 Moderate 15.0 23.9 33.3 Much 20.0 32.6 24.1 Great 45.0 23.9 16.7 Business environment None – 11.1 5.6 Little 15.0 4.4 9.3 Moderate 20.0 31.1 33.3 Much 40.0 33.3 31.5 Great 25.0 20.0 20.4 The following two items were scored on a 5-point scale with two anchors Moral obligation No obligation 21.1 26.1 35.2 No obligation 21.1 34.8 40.7 No obligation 26.3 19.6 16.7 No obligation 15.8 13.0 5.6 Strong obligation 15.8 6.5 1.9 Awareness of consequences a Should have 10.5 10.9 7.4 Should have 10.5 8.7 11.1 Should have 21.1 19.6 14.8 Should have 15.8 34.8 20.4 Should not have 42.1 26.1 46.3 Case B (software sent in error was kept) Females Males 1164 Frequencies Case A (programmer manipulates accounting system) Females Males IMDS 105,9 166 49.7 168 50.3 334 46 70.8 19 29.2 65 145 54 37.2 91 62.8 252 133 52.8 119 47.2 303 138 45.5 165 54.5 85 47 55.3 38 44.7 96 32 33.3 64 66.7 276 146 52.9 130 47.1 265 128 48.3 52 44.8 116 137 51.7 64 55.2 Case A Case B Case C Case D Case E Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Acceptable Unacceptable Note: Indicates the percent acceptable for each case, or unacceptable for each case. a Males N Percenta Females N Percenta Total N Frequencies A shifting model 1165 Table VI. Summary for acceptable/unacceptable decisions by male and female IMDS 105,9 Female 1166 Table VII. Comparison of gender findings Model classification rate (percent correctly classified) Male Case A Moral obligation Consequences Societal environment 77.5 Case B Moral obligation Belief system Professional environment 80.2 Case C Moral obligation Personal environment 78.9 Case D Moral obligation Belief system Personal values Personal environment Legal environment Case E Moral obligation Societal environment Business environment 76.4 76.7 Moral obligation Consequences Belief system Legal environment Moral obligation Belief system Consequences Personal values Societal environment Moral obligation Consequences Personal values Business environment Moral obligation Personal values Consequences Professional environment Societal environment Moral obligation Personal values Model classification rate (percent correctly classified) 79.3 75.7 74.8 70.6 69.7 Discussion and conclusions The purpose of this research was to determine whether environmental factors, moral obligation, and awareness of consequences influence an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior and to compare those findings to Kreie and Cronan’s (1999) work to see if the attitude influencers have changed, and to test if gender differences exist as well. The proposed model suggests that an individual’s attitude toward ethical behavior is influenced by society, by the professional, legal, and business environments, and by one’s belief system, personal values, personal environment, moral obligation and awareness of consequences. The influences of these environmental factors varied, and have changed from the Kreie and Cronan study, based on the ethical issues involved. Many of the proposed model’s influences do exist and attitude has many dimensions. However, only moral obligation and consequences influence attitude, consistently, when testing individual cases, as compared to the Kreie and Cronan study where moral obligation and legal environment were of highest importance. Perceptions of the cases, as being acceptable or unacceptable, have not changed but the variables of influence have shifted. Referring to Table III, it is interesting that legal environment is no longer an influence, especially since more laws are in effect than there was in 1999. Respondents seem more concerned about consequences, if any, and not the laws that do exist. Also, looking at individual cases, none of the exact same influences exist as were stated by Kreie and Cronan; all five cases resulted in different variables of influence than found in the previous study. Clearly, the attitude influencers have changed over time and do depend on the situation being assessed. Attitude could change continually as new influences are introduced, or society changes. Therefore, attitude influencers will need to be reassessed as changes over time occur in society. The influence of gender was also assessed. The findings indicate that attitude has many dimensions for males and females, and the attitude influencers not only depend on the behavior in question but on the gender of the individual. Females generally viewed the behaviors in question as more unacceptable (i.e. unethical) than males, and males viewed the behaviors in question as more acceptable (i.e. ethical) than females. Female attitudes toward ethical behavior depended on moral obligation in all cases examined. However, depending on the situation, various influencers were present which indicates that females assess the situation and do not rely on the same factors for all cases. Male attitudes toward ethical behavior depended primarily on moral obligation, awareness of consequences, and personal values. Therefore, males have a given set of parameters when assessing a situation, where as females adjust their parameters based on the situation. For example in case C (company equipment that was used on personal time), moral obligation and personal environment were influencers for females, and moral obligation, consequences, personal values, and business environment were influencers for males. In this situation it appears that women are influenced by their peers, and men are influenced by their own personal goals, corporate goals, and the possible consequences of their actions. This clearly shows how one’s attitude can be different based on gender, given that the influencers are so drastically different. Since the ethical attitude of an individual in any given situation is dependent on many factors, both internal (personal values, belief system) and external (societal environment, legal environment, etc.), an assessment of individual situations would be useful in comparing the impact of different issues (cases). Additional information technology issues should, therefore, be considered when assessing attitude toward ethical behavior. Further research is needed to identify influences on attitude toward ethical behavior. Also, attitude influencers have shifted over time, which means that organizations must continually assess their employees’ ethics’ climate and adjust their ethics’ programs as attitude influencers change. Given the gender findings, training programs need to focus on the different influencers for males and females. Also, emphasis should be placed on establishing the importance of the influencers that might create more ethical behavior for males or females. Future research should seek to further the gender findings by studying a professional setting. Notes 1. Many research studies have used students as subjects. Students have been assumed to be suitable surrogates for business managers and decision makers. Results should be generally applicable to actual business managers, which is especially the case when researchers are interested in the ethical decision-making process. Student samples can be used without a major threat to generalizability (“Methods in Business Ethics”, Journal of Business Ethics, 9(6), June 1990, p. 463). 2. N varies for some analyses because of incomplete responses. References Aiken, R.M. (1988), “Reflections on teaching computer ethics”, paper presented at the Fourteenth SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, pp. 8-11. A shifting model 1167 IMDS 105,9 1168 Ajzen, I. (1989), “Attitude, structure and behavior”, in Pratkanis, A.R., Breckler, S.J. and Greenwald, A.G. (Eds), Attitude, Structure and Function, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. Ajzen, I. (1991), “The theory of planned behavior”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 179-211. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1969), “The prediction of behavior intentions in a choice situation”, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 5, pp. 400-16. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980), Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Banerjee, D., Jones, T.W. and Cronan, T.P. (1996), “The association of demographic variables and ethical behaviour of information system personnel”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 96 No. 3, pp. 3-10. Bommer, M., Gratto, C., Gravander, J. and Tuttle, M. (1987), “A behavioral model of ethical and unethical decision making”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 6, pp. 265-80. Bowie, N.E. (2005), “Digital rights and wrongs: intellectual property in the information age”, Business and Society Review, Vol. 110 No. 1, pp. 77-96. Conner, K.R. and Rumelt, R.P. (1991), “Software piracy: an analysis of protection strategies”, Management Science, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 125-39. Cougar, J.D. (1989), “Preparing IS students to deal with ethical issues”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 211-8. Dawson, L.M. (1997), “Ethical differences between men and women in the sales profession”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 16 No. 11, pp. 1143-52. Deshpande, S.P. (1997), “Managers’ perception of proper ethical conduct: the effect of sex, age, and level of education”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 79-85. Eining, M.M. and Christensen, A.L. (1991), “A psycho-social model of software piracy: the development and test of a model”, in Dejoie, R., Fowler, G. and Paradice, D. (Eds), Ethical Issues in Information Systems, Boyd and Fraser, Boston, MA. Ferrell, O.C. and Gresham, L.G. (1985), “A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49, pp. 87-96. Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. Foltz, C.B., Cronan, T.P. and Jones, T.W. (2005), “Have you met your organization’s computer usage policy?”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 105 No. 2, pp. 137-46. Gattiker, U.E. and Kelley, H. (1999), “Morality and computers: attitudes and differences in moral judgments”, Information Systems Research, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 233-54. Haugen, S. and Selin, J.R. (1999), “Identifying and controlling computer crime and employee fraud”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 99 No. 8, pp. 340-4. Heide, D. and Hightower, J.K. (1988), “Teaching ethics in the information sciences curricula”, Proceedings of the 1988 Annual Meeting of the Decision Sciences Institute, pp. 198-200. Higgs-Kleyn, N. and Kapelianis, D. (1999), “The role of professional codes in regulating ethical conduct”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 363-74. Hubbard, J.C. and Forcht, K.A. (1998), “Computer viruses: how companies can protect their systems”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 98 No. 1, pp. 12-16. Kreie, J. and Cronan, T.P. (1998), “How men and women view ethics”, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 41 No. 9, pp. 70-6. Kreie, J. and Cronan, T.P. (1999), “Copyright, piracy, privacy, and security issues: acceptable or unacceptable actions for end users?”, Journal of End User Computing, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 13-20. Leonard, L.N.K. and Cronan, T.P. (2001), “Illegal, inappropriate, and unethical behavior in an information technology context: a study to explain influences”, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Vol. 1 No. 12, pp. 1-31. Leonard, L.N.K., Cronan, T.P. and Kreie, J. (2004), “What are influences of ethical behavior intentions – planned behavior, reasoned action, perceived importance, or individual characteristics?”, Information & Management, Vol. 42 No. 1, pp. 143-58. Loch, K.D. and Conger, S. (1996), “Evaluating ethical decision making and computer use”, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 39 No. 7, pp. 74-83. McCollum, T. (2004), “E-crime rises despite security precautions”, The Internal Auditor, Vol. 61 No. 2, p. 21. Marshall, K.P. (1999), “Has technology introduced new ethical problems?”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 81-90. Mason, R.O. (1986), “Four ethical issues of the information age”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 4-12. Oz, E. (1990), “The attitude of managers-to-be toward software piracy”, OR/MS Today, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 24-6. Paradice, D.B. (1990), “Ethical attitudes of entry-level MIS personnel”, Information & Management, Vol. 18, pp. 143-51. Parks, L. (2005), “Beware the hidden internet”, Stores, Vol. 87 No. 3, p. LP14. Power, R. (2000), “2000 CSI/FBI computer crime and security survey”, Computer Security Journal, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 33-49. Rest, J.R. (1979), Development in Judging Moral Issues, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN. Saari, J. (1987), “Computer crime – numbers lie”, Computers and Security, Vol. 6, pp. 111-7. Schwartz, S.H. and Tessler, R.C. (1972), “A test of a model for reducing measured attitude-behavior discrepancies”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 225-36. Steinke, G. and Nickolette, C. (2003), “Business rules as the basis of an organization’s information systems”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 103 No. 1, pp. 52-63. Straub, D.W. and Nance, W.D. (1990), “Discovering and disciplining computer abuse in organizations: a field study”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 45-60. Trembly, A.C. (1999), “Cyber crime means billions in losses”, National Underwriter, Vol. 103 No. 26, p. 19. Trevino, L.K. (1986), “Ethical decision making in organizations: a person-situation interactionist model”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 601-17. Venkatesh, V. and Morris, M.G. (2000), “Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 115-39. Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G. and Ackerman, P.L. (2000), “A longitudinal field investigation of gender differences in individual technology adoption decision-making processes”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 83 No. 1, pp. 33-60. Victor, B. and Cullen, J.B. (1988), “The organizational bases of ethical work climate”, Administrative Science Quarterly, pp. 101-25. A shifting model 1169 IMDS 105,9 1170 Zalud, B. (1984), “IBM chief urges DP education, social responsibility”, Data Management, Vol. 22 No. 9, pp. 30-74. Appendix. Scenarios Case A A programmer at a bank realized that he had accidentally overdrawn his checking account. He made a small adjustment in the bank’s accounting system so that his account would not have an additional service charge assessed. As soon as he made a deposit that made his balance positive again, he corrected the bank’s accounting system. Case B With approval from his boss, a person ordered an accounting program from a mail-order software company. When the employee received his order, he found that the store had accidentally sent him a very expensive word processing program as well as the accounting package that he had ordered. He looked at the invoice, and it indicated only that the accounting package had been sent. The employee decided to keep the word processing package. Case C A computer programmer enjoyed building small computer applications to give his friends. He would frequently go to his office on Saturday when no one was working and use his employer’s computer to develop computer applications. He did not hide the fact that he was going into the building; he had to sign a register at a security desk each time he entered. Case D A computing service provider offered the use of a program at a premium charge to subscribing businesses. The program was to be used only through the service company’s computer. An employee at one of the subscribing businesses obtained a copy of the program accidentally, when the service company inadvertently revealed it to him in discussions through the system (terminal to terminal) concerning a possible program bug. All copies of the program outside of the computer system were marked as trade secret, proprietary to the service, but the copy the customer obtained from the computer was not. The employee used the copy of the program after he obtained it, without paying the usage fee to the service. Case E A marketing company’s employee was doing piece work production data runs on company computers after hours under contract for a state government. Her moonlighting activity was performed with the knowledge and approval of her manager. The data were questionnaire answers of 14,000 public school children. The questionnaire contained highly specific questions on domestic life of the children and their parents. The government’s purpose was to develop statistics for behavioral profiles, for use in public assistance programs. The data included the respondents’ names, addresses, and so forth. The employee’s contract contained no divulgement restrictions, except a provision that statistical compilations and analyzes were the property of the government. The manager discovered the exact nature of the information in the tapes and its value in business services his company supplied. He requested that the data be copied for subsequent use in the business. The employee decided the request did not violate the terms of the contract, and she complied. (Lori N. K. Leonard is an Associate Professor of Management Information Systems at the University of Tulsa. Leonard received her PhD from the University of Arkansas and is an active member of the Decision Sciences Institute. Her research interests include electronic commerce, electronic data interchange, ethics in computing, and online auctions. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Computer Information Systems, Information & Management, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, Journal of End User Computing, as well as in other journals, and Proceedings of various Conferences. Timothy Paul Cronan is Professor of Information Systems and M.D. Matthews Chair in Information Systems in the Walton College of Business, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Cronan received his DBA from Louisiana Tech University and is an active member of the Decision Sciences Institute and The Association for Computing Machinery. He has served as Regional Vice President and on the Board of Directors of the Decision Sciences Institute and as President of the Southwest Region of the Institute. In addition, he has served as Associate Editor for MIS Quarterly. His research interests include ethics in computing, local area networks, downsizing, expert systems, performance analysis and effectiveness, and end-user computing. His publications have appeared in Decision Sciences, MIS Quarterly, OMEGA The International Journal of Management Science, The Journal of Management Information Systems, Communications of the ACM, Journal of End User Computing, Database, Journal of Research on Computing in Education, Journal of Financial Research, as well as in other journals, and Proceedings of various Conferences.) A shifting model 1171