Sole Proprietorships

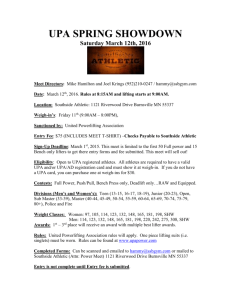

advertisement