expropriation of american-owned property by foreign

advertisement

1066

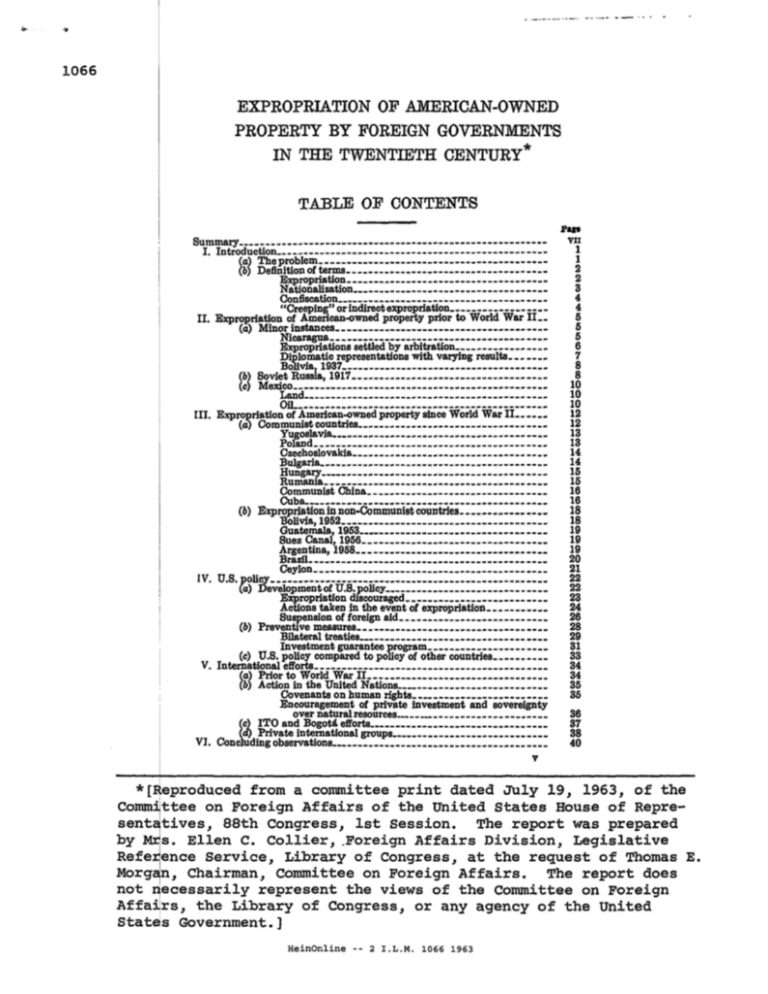

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED

PROPERTY BY FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS

IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY*

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pan

Summary

I. Introduction

(a) Theproblem

(6) Definition of terms

Expropriation

Nationalization

Confiscation

"Creeping" or indirect expropriation

II. Expropriation of American-owned property prior to World War II _.

(o) Minor instances

Nicaragua

Expropriations settled by arbitration

Diplomatic representations with varying results

Bolivia, 1937_(M Soviet Russia, 1917

(c) Mexico

Land

OU

III. Expropriation of American-owned property since World War II

(a) Communist countries

Yugoslavia

Poland

Czechoslovakia

Bulgaria

Hungary

Rumania

.

Communist China

Cuba

(b) Expropriation in non-Communist countries

Bolivia, 1952

Guatemala, 1953

Suez Canal, 1956

Argentina, 1958.

Brazil

Ceylon

IV. Ü.S. policy

(a) Development of U.S. policy

Expropriation discouraged

Actions taken in the event of expropriation

Suspension of foreign aid

(b) Preventive measures

Bilateral treaties

Investment guarantee program

(c) U.S. policy compared to policy of other countries

.

V. International efforts

(a) Prior to World War II

(6) Action in the United Nations

Covenants on human

rights

Encouragement of private investment and sovereignty

over natural resources

(c) ITO and Bogotá efforts

(a) Private international groups

VI. Concluding observations

v

VI1

1

1

2

2

3

4

4

5

5

5

6

7

8

8

10

10

10

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

18

18

19

19

19

20

21

22

22

23

24

26

28

29

31

33

34

34

35

35

36

37

38

40

*[Reproduced from a committee print dated July 19, 1963, of the

Committee on Foreign Affairs of the United States House of Representatives, 88th Congress, 1st Session. The report was prepared

by Mrs. Ellen C. Collier, .Foreign Affairs Division, Legislative

Reference Service, Library of Congress, at the request of Thomas E.

Morgan, Chairman, Committee on Foreign Affairs. The report does

not necessarily represent the views of the Committee on Foreign

Affairs, the Library of Congress, or any agency of the United

States Government.]

HeinOnline -- 2 I.L.M. 1066 1963

1067

SUMMARY

I. INTEODITCTION

Expropriation by foreign countries of property owned by ILS.

nationals is a problem for U.S. policy for three basic reasons. First,

the United States has a responsibility in protecting the property of

its citizens abroad. Second, such actions may impair good international relations and cause strained relations to deteriorate further.

Third, they inhibit the private investment in underdeveloped countries

which the United States has sought as one method of promoting

economic development.

Definitions of expropriation often include legal criteria for deciding

whether an action shall be classified as expropriation, particularly

that compensation must be made. The term is frequently used,

however: to denote any taking of private property by a government

for a public purpose in peacetime. In practice it nas been expropriations without satisfactory compensation which have caused

international problems.

II. EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY PRIOR TO WORLD

WAR II

Prior to the First World War expropriations involving foreign

property^ holders were infrequent. In 1917 the Russian revolution

ushered in the problem of nationalization of all private property by

Communist states. The Mexican land and oil expropriations ushered

in the problem of underdeveloped nations seeking to change the

status quo in regard to foreign control of important segments of the

economy.

The patterns of diplomatic action in the event of expropriation were

also set during this period. Diplomatic protests and representations

were first made, but if local remedies proved insufficient, claims were

referred to arbitrators or special commissions or héla for further

negotiation.

i n . EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY SINCE WORLD

n

Since the end of the Second World War, expropriations have increased. The most widespread expropriations nave occurred in the

countries which adopted communism. Agreements on lump sums to

settle claims arising from expropriations have been reached with

Yugoslavia, Poland, Bulgaria, and Rumania. Some of the claims

against Czechoslovakia and Hungary have been paid out of funds

established from assets of those countries in the United States. The

problem of obtaining compensation from Cuba and Communist China

is being held in abeyance since diplomatic relations are not maintained

with those nations.

WAR

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1067

1963

1068

SU3I3IAKY

vm

Not all of the postwar expropriations have occurred in Communist

countries. Most of the other major expropriations affecting U.S.

nationals have been carried out by Latin American countries. Exceptions are the Egyptian nationalization of the Suez Canal and the

expropriation of certain oil facilities by Ceylon. An agreement on

compensation was reached between the United Arab Republic and the

Suez stockholders in 1958. Foreign aid to Ceylon was suspended in

February 1963 under the terms of an amendment to the foreign aid

legislation.

In Latin America, one of the expropriations, that of the United

Fruit Co. property by Guatemala, was rescinded after a change in

overnment. rublic utility expropriations by local governments in

irazil and Argentina have been settled, with the United States making

diplomatic representations and the foreign courts evaluating the

property.

f

IV. U.S. POLICY

The United States has consistently acknowledged the right of a

sovereign nation to expropriate foreign-owned property, so long as the

taking conformed to the standards of international law; that is, that

ib was for a public purpose, not discriminatory against the United

States, and accompanied by just compensation. Just compensation

has been spelled out to mean prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. However, while acknowledging • the right of expropriation,

the United States has not encouraged it on the grounds that it would

discourage private investment, ^Expropriation without just compensation has been deemed a violation of international law, no matter

what the objectives of the expropriation.

The United States has initiated two programs to prevent problems

from arising. One of these is to negotiate bilateral treaties containing

agreements on the subject. The other is the investment guarantee

program which provides insurance against expropriation on approved

projects. This program probably reduces the likelihood of expropriation because it provides for agreement between the United States and

the foreign government concerned on the projects to be insured as

well as the procedures for settlement. In addition, the suspension of

foreign aid offers a tool for hastening compensation.

V. INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS

The problem of expropriation has been discussed at international

meetings at various tunes throughout the century. The two themes

that still battle for dominance in international conferences today

were discernible as early as 1922—on the one hand, that every State

has the rieht to regulate its own property; on the other, that foreign

capital wUl be made available only if a country provides a sense of

security.

After discussion on several occasions, the United Nations in 1962

adopted a resolution on permanent sovereignty over natural resources

which declared that expropriations should be based on reasons which

are recognized as overriding purely individual or private interests,

and that in such cases the owner should be paid appropriate compensation in accordance with the laws of the expropriating nation and

international law.

HeinOnline

2 I . L . M . 1068 1963

SUMMARY

IX

On at least two occasions multilateral treaties dealing with the

protection of foreign investors in the event of expropriation have been

drafted, but they have not entered into force in part at least because

the provisions, representing an attempt to reconcile the diverging

interests of the capital-exporting and capital-importing nations,

were unsatisfactory to one or both sides.

Codes for the protection of private investment have also been

drafted by private international organizations. Other proposals

include the establishment of tribunals to handle expropriation claims

and treaty commitments that expropriation of foreign property would

not be undertaken for a specified period, such as 30 years.

VI. CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

It is largely because the United States has wanted to assist in the

economic development of underdeveloped countries that active

measures have been taken to discourage expropriation by the underdeveloped coxmtries. Otherwise, the United States could be content

with taking legal measures to secure just compensation after expropriations occurred. The expropriation problem would then take

care of itself, the level of private investment decreasing in countries

which had carried out excessive expropriations. Because the United

States did want to encourage private investment to play a role in

economic development, however, the United States has taken the

initiative in devising policies to prevent expropriations which would

inhibit such private investment.

H e i n O n l i n e - - 2 I . L . M . 1069 1963

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY BY

FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS IN THE 20TH CENTURY

I . INTRODUCTION

(A) THE PROBLEM

During this century expropriation by foreign governments of property owned by U S . nationals has grown into a thorny problem^ m

U.S. foreign policy. Such expropriations, once for the most part isolated and small incidents affecting only a few individuals, have increased both in frequency and size.

Although many diverse factors are undoubtedly involved, this

expansion appears to stem primarily from two ideological forces or

their interaction. One is nationalism and the desire of a country to

manage its own affairs without foreign influence. The other is

Marxism, be it Socialist or Communist, and its call for state ownership

or operating of the means of production, or other changing concepts

of property.

Aside from the ideological challenges involved in dealing with these

forces, from the practical point of view the upward trend of foreign

expropriations poses concrete problems for U.S. foreign policy.

One of these problems has long existed. It concerns the function of

a nation in protecting its citizens and their property abroad. Expropriations which are not accompanied by satisfactory compensations

involve the government in the ensuing controversy between the

expropriated property holder and the expropriating country. They

result in claims which at best require a great deal of time and effort

to resolve and at worst impair good international relations or cause

strained relations to deteriorate further.

Another problem, of more recent origin, concerns sustaining and

encouraging private investment in the underdeveloped areas of the

world. Assistance to underdeveloped countries in improving their

living standards and achieving economic development is a part of

U.S. foreign policy, and private investment one means of assistance.

President ^Kennedy stated in his message on the mutual defense and

assistance programs:

Economic and social growth cannot be accomplished by governments alone.

The effective participation of an enlightened U.S. businessman, especially in

partnership with private interests in the developing country, brings not only

bis investment but bis technological and management skills into the process of

development. His successful participation in turn helps create that climate of

confidence

which is so critical in attracting and holding vital external and internal

capital.1

In the same message President Kennedy announced that the primary initiative in this year's program related to "increased efforts to

encourage the investment of private capital in the underdeveloped

> Congressional Record. Apr. 2,1963, p. 512«.

HeinOnline - - 2 I.L.M. 1070 1963

1071

2

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

areas." Accordingly, increasing constructive private investment

abroad, particularly in the underdeveloped areas, has become an

objective of U S . foreign policy.

It is apparent that the expropriation of property owned by Americans abroad without satisfactory compensation, or even the fear of

such expropriation, has a direct bearing on private investment abroad.

Businessmen will be reluctant to invest in countries in which they face

the risk of loss through expropriation in addition to normal risks. A

Department of Commerce survey in 1953 of factors in foreign countries

limiting U.S. investments abroad included the threat of inadequately

compensated expropriation or nationalization among the principal

impediments to private investment in Latin America and an important

one> in the Far Bast.2 In addition, the survey found the threat of

nationalization affected the investment climate in a number of countries in the Near East and Africa and in some countries of Western

Europe.3

Finally, the foreign aid program has become more directly involved

in the problem because it presents a possible tool of policy in expropriation cases which was not available in the past.

The purpose of this report is to bring together some of the widely

scattered information on the expropriation problem, review the expropriations which have occurred, and trace the development of U.S.

policy. In addition, a survey will be made of actions taken or proposals made on the problem by various groups.

(B) DEFINITION OP TERMS

A discussion of the meaning of "expropriation" and related concepts

may help clarify the scope of the problem.

Expropriation

Webster defines expropriation as "the action of the state in taking

or modifying the property rights of individuals in the exercise of its

sovereignty, as where property is sold under eminent domain." * This

right of a state is recognized in the fifth amendment to the Constitution which provides " * * * nor shall private property be taken for

public use, without just compensation." It is frequently exercised in

the United States for such purposes as acquiring land for new roads or

other public projects.

Controversy arises, however, on the question of whether compensation must be rendered if an act of taking by the state is to be classified

as expropriation. Some hold that compensation is a separate element.

For example, one authority on the subject defines expropriation as

"the procedure by which a state in time of peace and for reasons of

public utility appropriates a private property right, with or without

compensation, so as to place it at the disposal of its public services, or

of the public generally." *

Others define expropriation more narrowly to include only the acts

of taking for which compensation is rendered, uncompensated takings

being termed confiscations. Along this line, one authority includes

> U.8. Department of Commerce, "Factors Limiting U.S. Investment Abroad," pt. 1, "Survey of Factors

in Foreign Countries," Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 6 and 101.

* Ibid., pp. 46 and 75.

< "Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language," second edition, unabridged, 1053.

• Friedman, S., "Expropriation in International Law/' London, Stevens & Sons, Ltd., 1953, p. 3.

H e i n O n l i n e - - 2 I . L . M . 1071 1963

1072

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

3

"adequate and prior compensation" as an element in his definition of

"expropriation in its classical form." e

Similarly, the United States has at times taken the position that to

be considered expropriation, an act of taking requires compensation.

In a note to Mexico m 1938, the Secretary of State wrote: "The taking

of property

without compensation is not expropriation. It is confiscation." 7 Frequently, however, the Department of State also uses the

term "expropriation" in its broad form to encompass any taking of

property by a government for public purposes. For example, a list

of expropriations compiled by the Department of State in 1962 was

made up largely of those

for which adequate compensation had not

been readily obtained.8

The definition found in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1962 emphasizes that expropriation includes intangible property rights. It states

(Public Law 87-565, sec. 223 (b)):

* * * the term "expropriation" includes but is not limited to any abrogation,

repudiation, or impairment by a foreign government of its own contract with an

investor, where such abrogation, repudiation, or imçairment is not caused by

the investor's own fault or misconduct, and materially adversely affects the

continued operation of the project.

In order to avoid judgment as to whether adequate compensation

has been rendered and therefore an action can be described as "expropriation," or whether instead it should be referred to as "confiscation," experts in international law sometimes use the neutral word

"taking." In this report the term "expropriation" will be used interchangeably with "taking" to denote any taking of private property by

a government during peace for a public purpose. However, the report

will be concerned mainly with those expropriations for which satisfactory compensation was not immediately made, for they are the ones

which have threatened the owners with loss, become issues in international relations, and inhibited foreign investment.

"Expropriation" is a term usually applied only to direct investments

abroad; that is, investments which involve the element of proprietorship and permit the investor

to control or exercise some influence on

their business operations.B The problem of losses suffered by American holders of foreign bonds through defaults has not been included

in this study.

NaMonclization

Most of the major expropriations during this century have arisen

from nationalizations. This term also has been defined in a variety

of ways. One writer describes nationalization as—

the process whereby property, and rights and interests in property, are transferred

from private to public ownership by agents of the state acting on the authority of

a legislative or executive measure. After transfer, the property remains in10 the

ownefship of, and is exploited by, the state or a body created by the state.

•7 Wortley, B. A., "Expropriation in Public International Law," Cambridge, University Press, 1959. p. 24.

Note from the Secretary of State of the United States to the Ambassador of Mexico dated July 21,1938.

. r Instances of Expropriation of Property Belonging to U.S. Nationals Since

, . ,,„„„ ¿j..-=,3ConunitteeonForeignRelatlons,U.8.Senate,onS.2998,ForelcnAssIstance

Açtofl982,87tbCong.,2dsess.,8.Kept.l535,p.93.

. . J r 8 Sr don <.î 0 ¥* £•• Marcus Nadler, and Harry C. Sauvain, "America's Experience as a Creditor Natton,"New York, Prentice-Hall, 1937, pp. 8-9.

» Whito, Gillian, "Nationalisation of Foreign Property," London, Stevens & Sons, 1061, p. 42.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1072

1963

4

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

Another definition emphasizes that the intention of a state in a

nationalization is to take over an operation previously conducted by

private owners:

* * * nationalization may be defined as the compulsory transfer t o the state

of private property dictated b y economic motives and having as its purpose the

continued and essentially unaltered exploitation of the particular property."

A number of differentiations between nationalization and expropriation have been made by various authorities. One writer claims,

however, that "nationalization differs in its scope and extent I2rather

than in its juridical nature from other types of expropriations." At

any rate, because nationalization is the type of expropriation which

in practice has involved the largest amounts of property, it is the kind

which has most frequently been involved in international controversies.

Confiscation

It seems widely agreed that confiscation means a taking of property

by a government without compensation. It has been defined as

"any government action by which private property is seized without

compensation, no matter in what form or under what name." l3

Either nationalizations or expropriations are apt to be called confiscations if they are not accompanied by adequate and prompt compensation. Since differences may exist on what constitutes adequate and

prompt compensation, however, the term is used cautiously except in

those instances in which a nation taking property makes it clear that

it has no intention of making any kind of compensation.

" Creeping" or indirect expropriation

Sometimes expropriation occurs in effect not as a direct act but as

the byproduct or indirect result of some other governmental action.

In recent years the term "creeping expropriation'' has been employed

to describe those indirect measures which may sooner or later produce

the same effect as direct expropriation; that is, the divesting of a

private owner of his property and putting it in the hands of the state.

Among the measures which have been encompassed in the phrase

are fines, discriminatory taxes, labor requirements, regulation of

prices or utility rates, limitations on the percentage of foreign ownership or foreign employees, limitations on profits or on the right to

transfer them, and limitations on imports and the use of foreign

exchange earnings.14

"Creeping expropriation" may be more difficult to recognize than

direct expropriation since many of these measures are utilized to some

extent by most countries. One writer has pointed out that the

question of degree of interference with property by the state becomes

important, and that it may be extremely difficult to determine when

normal regulation ends ana expropriation begins.

If it remains within certain usual limits, such interference is deemed not to be

expropriation of part of the whole property; but if it exceeds certain limits it is

said to constitute partial expropriation. It cannot, however, be denied that it

11 Fofghel, Is!, "Nationalization, a Study in the Protection of Alien Property in International Law,"

Copenhagen, 1957, p. 19.

" Wortley, op. cit., p. 36.

ii Adrlaanse, P., "Confiscation in Private International Law," The Hague, Martin« Nilhoff, 1956, p. S.

" House Subcommittee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Foreign Trade Policy, hearings on

"Private Foreign Investment," Dee. 1-5.1958, p. 28: and Kuebler, Jeanne, "Protection of Investments in

Backward Countries," Editorial Sesearen Reports, July 11,1962, p. 611.

HeinOnline

- - 2 I.L.M.

1073 1963

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

Ö

may often be very difficult to decide whether or not in a special case the limits

of usual interference

have been reached or transgressed and, therefore, expropriation occurred.15

II. EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY PRIOR

TO WORLD WAR II

According to the Department of State, no complete list of expropriations by foreign governments of property owned by U.S. nationals

appears to have been maintained by any U.S. Government agency."

Many expropriations, particularly those which are preceded or

promptly accompanied by satisfactory compensation, never are

brought to the attention of the State Department. Some may be

brought to the attention of the embassy in the country involved and

be tiie subject of diplomatic attention without being recorded in a

central place. Apparently even the formal claims arising from expropriations which have been .submitted against other governments have

not been separated out from claims pressed for other reasons. Nevertheless, from research in published materials it is possible to piece

together a general picture of the extent and nature of expropriation of

American-owned property during this century.

(A) MINOR INSTANCES

Prior to the First World War expropriations involving foreignproperty holders were infrequent and involved relatively small holdings. After the Russian revolution in 1917, nationalizations began

and expropriation became a more aggravating problem. In the interwar period several of the Eastern European countries expropriated

land dunng agrarian reform programs, and Mexico carried out a land

reform program and expropriated foreign oil properties. In addition, Nazi Germany confiscated the property of Jews and took various

private property in the occupied countries.

Following are instances of expropriation from which the development of U.S. policy may be traced.

Nicaragua

One unusual series of expropriatory actions affecting Americanowned property appears to have taken place early in this century

when several concessions granted to Americans or American companies in Nicaragua were canceled. This resulted primarily from

the fact that a large number of concessions had been issued during the

regime of President Zelaya (1893-1909). In one instance a concession

granted under President Zelaya in 1894 was annulled by him in 190G

on allegations that the terms of the concession had not been fulfilled.

The concession had granted an American corporation the exclusive

right to out timber within a specified zone. The corporation, the

George D. Emery Co., submitted a claim for $1,048,154.28 which

was settled

for $600,000 through diplomatic channels on September 18.

1909.»7

" Hera, John H., "Expropriation of Foreign Property," American Journal of International Law, Apri 1

1941. vol. 35,0.243.

» "Major Instances of Expropriation of Property Belonging to U.S. Nationals 8lnce World War II,"

op. cit., p. 93.

» Whfteman, Mariorie M., assistant to, the Legal Adviser of the Department of State, "Damages in

International Law," U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943, vol. Ill, pp. 1043-1645.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1074

1963

1075

6

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

Most of the cancellations of concessions, however, occurred after

the revolution of 1909 deposed the Zelaya government and, with the

assistance of intervention by the United States, a new government

came into power. In a law of October 14,1911, the National Assembly

ordered the cancellation of contracts and concessions deemed illegal

or unconstitutional because they involved monopolies or for other

reasons. Upon the advice of the United States, which was assisting

Nicaragua in finding "the 'most efficient method of securing a stable

government for Nicaraguau and reconstructing the country's finances

and economic situation" a Mixed Claims Commission was established. The Commission, composed of two members selected upon

the initiative of the United States and one upon the initiative of

Nicaragua, was to adjudicate claims arising from these cancellations

and from other causes. Subsequently several claims were filed by

Americans with the Commission because of cancellations of concessions

on the ground that the Government had otherwise broken or failed to

fulfill a contract. The Mixed Claims Commission, which either

assisted in the settlement of or rejected the claims, later reported

that—

during the Zelaya regime, the country had been plastered with concessions which

were regarded as unconstitutional, illegal, and burdensome monopolies, and of

which many were held by foreigners. * * * The liquidation of the claims and the

cancellation of illegal concessions were among the necessary incidents in the task

of rehabilitating the financial and economic condition of the country.1'

Expropriations settled by arbitration

The Nicaraguan incidents illustrate two chief methods which have

traditionally been employed in controversies over expropriations:

diplomacy and the establishment of claims commissions. Three cases

were found in the early part of the century in which claims arising

from expropriation were settled by arbitration.

Two of these instances were in Cuba. In 1919 the mayor of

Marianao began expropriationproceedings to condemn property

owned by on American citizen, Walter Fletcher Smith, for the benefit

of a private company. Before the expropriation procedures were

complete, the buildings on the property were destroyed, apparently

under the direction of the private company. A private arbitration

was arranged between the American citizett and the private company,

and the arbitrator awarded Mr. Smith $190,000 of his claim of

$515,000.

In the other early instances involving Cuba, the President of Cuba

by a 'decree of September 22, 1925, designated certain lands to be

expropriated for the purpose of building a national penitentiary.

Among these lands was some belonging to two American citizens,

T. J. Keenan and Dr. Albert Pettit. One of the Americans protested

the evaluation placed on the land by the Government and the matter

was arbitrated by President Machado

of Cuba and the American

Ambassador, Enoch H. Crowder.20

The incident in Guatemala occurred on May 22, 1928, when the

Guatemalan Legislative Assembly passed a decree canceling a conti Nicaraguan Mixed Claims Commission, report submitted to the Secretary of State, Jan. 20,1915, p. 16.

» Nicaraguan Mixed Claims Commission, loe. cit.

» Wbtteman, op. dt., p. 1392.

HeinOnline -- 2 I.L.M. 1075 1963

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

7

cession for the extraction of chicle from the national forests within a

certain area. The concession, originally granted in 1922 to two

Guatemalan citizens, had been purchased by an American citizen,

P. W. Shufeldt. The amount offered Mr. Shufeldt by the Guatemalan

Government in settlement, $80,000, was refused as inadequate.

Mr. Shufeldt placed his claim before the Department of State and

the American Minister to Guatemala was instructed to take up the

matter informally with the Government of Guatemala with the aim of

arriving at an amicable settlement. Later, the American Minister

informed Guatemala that the United States believed Mr. Shufeldt's

claims were meritorious and formally requested a settlement, claiming

losses and damages of $561,800.

In reply, the Government of Guatemala suggested arbitration.

The arbitrator selected was the Chief Justice of British Honduras, who

awarded the United States $225,468.38 on July 24, 1930."

Diplomatic representations with varying results

Three early cases of proposed expropriations of American-owned

property illustrate the varying results of diplomatic representations or

protests.

In one instance a planned nationalization was not carried through

after diplomatic representations were made. On March 26,1937, the

American Embassy in Spain reported that the Royal Typewriter Co.

had requested representations in its behalf to prevent the collectivization of its Spanish distributing agency by the employees of the agency

pursuant to a decree of October 24,1936. The company claimed that

the stock of the distributing agency was totally owned by American

citizens, for whom collectivization would result in complete loss.

The Department of State instructed the Embassy to bring the matter

to the attention of the Spanish Government and. without passing upon

the validity of the decree, to state that the American Government

expected "prompt and full compensation of all American nationals or

concerns for any losses suffered by them as the result of the collectivization of businesses or concerns in which they are interested." In a

note verbale of December 14, 1937, the Spanish Ministry of State

advised the American Embassy that the collectivization of the distributing agency had been annulled.M

In another case, an act of indirect expropriation was postponed

to diminish the amount of loss suffered by foreign nationals. An

Italian law of April 4, 1912, established a state insurance monopoly

of life insurance. There were several foreign insurance companies

operating at the time, and the countries whose nationals would be

affected, the United btates, the United Kingdom, France, Austria,

Hungary, and Germany, lodged diplomatic protests. The enforcement of the law was postponed and the foreign companies were allowed time to liquidate their business, though no compensation was

made for loss

of business. The real property of the companies was

not touched.23

_ _ O.S. Department of State, arbitration series No. 3, Shufeldt claim, Washington, Government Printing

Office, 1932,911 pages.

" Haokworth, Oreen Haywood, "Digest of International Lawj" Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943, p. 588.

» Hackworth, op. cit., p. 588; Borchord, Edwin, "Diplomatic Protection of attains Abroad," New

York, Banks Law Publishing Co., 1925, p. 126.

20-821—63

3

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1076

1963

8

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

In a third case, another instance of indirect expropriation, diplomatic proteste were unsuccessful. First the Japanese Government

in 1934 required foreign oil companies to store a 6-month supply

of oil there and sell it to the Government at a fixed price. The following year the Japanese-controlled Manchukuoan Government

created an oil monopoly in which only the Japanese oil companies

could participate. Foreign companies, which had been doing an

extensive business in Manchuria and some of which had built up

extensive sales organizations, were permitted only to import and

engage in refining under license.24

The countries involved, the United States, Great Britain, and .the

Netherlands, directed protests to Japan against the monopoly,

contending it violated the treaty pledge to respect the principle of

equality of trade opportunity. However, Japan took the position that

Manchukuo was an independent state and that protests should be

directed to the Manchukuoan authorities, whom the protesting

governments did not recognize. In addition, Japan refused to modify

its own laws concerning foreign oil companies.2*

Bolivia, 19S7

One additional action should be mentioned before going into the

major examples of Russia and Mexico. This was the taking by

Bolivia of the oil properties of the Standard Oil Co. on March 13,1937.

The oil company had been prospecting for petroleum by virtue of

grants made m 1920. In taking the property valued by the company

at $17 million, President Toro alleged that the corporation bad

evaded the payment of rentals of petroleum lands. A Bolivian

company was 'directed to take charge of the oil properties. The

American company maintained that it was not guilty of the alleged

fraud and protested the seizure, but local courts refused compensation.

In 1942, however, the Peñaranda government agreed, to pay the

Standard Oil Co.

$1,750,000 for the petroleum properties which

had been taken.30

(B) SOVIET RUSSIA, I9I7

A study of expropriation as an important problem in the 20th

century may really begin with the Communist revolution in Russia

in 1917. Confiscation of private property formed a fundamental part

of the revolution, and nationalizations were made on a vast scale to

carry out the Marxist doctrine (»ailing for the socialization of the

means of production.

In February 1918, soon -after the czarist government had been

overthrown, decrees were issued by the new government abolishing

private ownership of land, minerals, forests, natural resources^ and

agricultural holdings and equipment. The assets of former private

banks were confiscated and banking was made a state monopoly.

Similarly the merchant fleet, foreign trade enterprises, and insurance

businesses were nationalized. By June 1920 most industry had been

socialized.

» Vlnacke, Harold M., "A History of the Par East in Modem Times," New York, Apple ton-CenturyCrofts, Inc., 1969, p. 624.

u Madden, John T., op. cit., p. 266.

it Robertson, William Spence, "History of the Latin-American Nations," New York, D . AppletonCentury Co., 1943, pp. 309-311.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1077

1963

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

9

Regional and local Soviets as well as the Central Government

undertook confiscations. Although on February 16, 1918, the Supreme Council of National Economy passed a resolution stating that

only that body and the Soviet of People's Commissars had the right

to confiscate enterprises, 2 months later the Supreme Council noted

that local groups were continuing to confiscate and nationalize enterprises. The Council stated that if this continued,27 it would not

appropriate money to run the confiscated enterprises.

During these actions, most of the foreign investments in Soviet

Russia were expropriated, with American

investments representing

an estimated 5 percent of the total'.28 Most of the American investments were in trade, financial, or insurance enterprises, although

there were some manufacturing establishments involved. Among

the American enterprises losing property were the International Harvester Co., the Otis Elevator Co., the Singer Manufacturing Co., the

National City Bank of New York, the New York Life Insurance

Society, and the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States.

The Soviet Government refused to either make restitution or pay

compensation for the foreign property which was seized, and diplomatic protests were lodged by the Allied Powers and some of the

neutrals. On February 13, 1918, the U.S. Ambassador protested in

the name of the 14 Allied Powers and 16 neutrals. The note of

protest stated:

In order to avoid any misunderstandings in future, the representatives at

Petrograd of all the foreign powers declare that they view the decrees relating to

the repudiation of the Russian state loans, the confiscation of property and other

similar measures as null and void insofar as their nationals are concerned."

After the war the Soviet Union continued to refuse to make any

compensation, and offered to recognize foreign claims only as part of

a general settiement which would include the satisfaction of Soviet

claims arising from the military intervention of the Allies after the

October revolution. This was an important factor in the U.S. refusal

to recognize the Soviet Union prior to 1933.

In the exchange of communications by which the United States

recognized the Soviet Government on November 16,1933, the Government of the Soviet Union released and assigned to the U.S. Government

all amounts due the Soviet Government from American nationals.

This agreement, known as the Litvinov assignment, formed the basis

of a fund outiof which some of the claims by American nationals against

Russia for confiscation of their property could be paid. Although the

Litvinov assignment was intended to be only preparatory to a final

settlement of the claims and counterclaims, subsequent negotiations

between the two Governments

on an overall final settlement have so

far proved unsuccessful.30 Meanwhile, some of the claims of American

nationals have been paid from the Litvinov assignment funds by the

Foreign Claims Settlement Commission under title H I of the Liternational Claims Settlement Act of 1949, as amended.

» Bunyon, Tames, and H. H. Fisher, "The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-18," Stanford University Press,

1934J). 612.

a U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign end Domestic Commerce, "Foreign Capital Investments in Russian Industries and Commerce." translation, miscellaneous series No. 124, by Leonard J.

Lewery, Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1923, p. 27.

» Friedman, S., op. cit., p. 18.

*> D.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Halations, staff memorandum on claims programs administered by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission under the International Claims Settlement

Act of 1949,88 amended, committee print, March 1963, p. 7.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1078

1963

1079

10

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

(C) MEXICO

At about the same time that the Communist revolution in Russia

was resulting in the confiscation and nationalization of almost all

private property, a social revolution in Mexico was resulting in the

expropriation of some for a land reform program and leading to a

large-scale expropriation of oil.

Land

One of the major objectives of the social revolution launched in

Mexico by the adoption of a new constitution in 1917 was land reform,

especially to restore to the peasantry the common lands which had

once been appurtenances of Mexican villages but had to a large extent

been absorbed in private estates of either Mexican or foreign owners.

In contrast to the Soviet Union, the declared intention of Mexico

was not to confiscate but to expropriate property with compensation.

The 1917 Constitution of Mexico stated that private property should

not be expropriated except for reasons of public utility and by means

of indemnification, and the land was taken by eminent domain at

appraised valuation, with payment in national bonds. Nevertheless,

difficulties with foreign nationals arose over the appraisals and the

method of payment.

In the Bucareli agreement of 1923 the representative of the United

States agreed that the land for commons could be paid for in bonds up

to 1,755 hectares, but that taking of acreage above that figure was

to be paid for in cash, and that the owner might appeal to a general

mixed claims commission regarding the appraised valuations. It was

stated that the payment in bonds of this limited group of agrarian

claims was not to constitute a precedent for future expropriations.

In regard to properties of American citizens taken after 1927,

following a series of diplomatic representations, Mexico in 1938 agreed

to pay for them after their value was fixed by a mixed commission

•composed of one representative of each government. In cases where

the commission disagreed, an umpire was to decide. Meanwhile, the

Mexican Government agreed to pay $1 million in May 1939 and after

that at least $1 million on each June 30 until the awards were paid.31

In a claims convention signed November 19, 1941, Mexico agreed

that in addition to the $3 million already paid on agrarian claims

.arisina: between August 30, 1927, and October 7, 1940, an additional

$3 muhun was to be paid upon exchange of ratifications of the agreement, and the remaining $34 million was to be liquidated over a

period of years through the annual payment by Mexico of $2,500,000

beginning in 1942.

Mexico still expropriates property, sometimes owned by U.S.

nationals, under its agrarian reform program. According to the

Department of State, while there has been no overall settlement of

•claims, there have been isolated instances of individual settlements.32

OÜ

The well-known Mexican oil expropriation began in the manner of

"creeping expropriation" but terminated in direct and complete

•expropriation.

«U.ff. Department of State, "Compensation for American-Owned Lands Expropriated in Mexico,"

foil text of official notes, July 21, 1937, to Nov. 12,.1937. Department of State publication 1288, interAmerican series 12, p. 45.

» "Major Instances of Expropriation • * V ' op. cit., p. 93.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1079

1963

1080

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

11

Before the Mexican revolution, the petroleum industry was controlled by private owners, for the most part foreign, who had bought

large tracts of land including the subsoil petroleum deposits. Under

the constitution of 1917, however, subsoil petroleum deposits were

brought under the ownership of the state. A series of provisional

decrees laid down the new conditions under which the previous owners

might continue to exploit their holding for terms of up to 50 years

under licensed concessions. Among these conditions were the so-called

Calvo clause—fjhat the concessionaires agree not to call upon their

governments for support of their titles against the Mexican Government.

In the diplomacy that followed, the United States took the position

that, although it did not deny the right of a nation to reform its constitution and legislation in its own ways, such reforms could not be

applied ex post facto to property rights already legitimately secured

by foreign nations under earlier constitutions and laws. In addition,

the United States contended that a foreign national could not sign

away the right to protection by his government without the consent

of his government. Under President Harding, Secretary of State

Charles Evans Hughes-insisted that recognition of the Mexican Government was contingent

upon a treaty which would bind Mexico to

adequate guarantees.83

Nevertheless, on August 31, 1923, formal recognition was extended

to the Obregon government on the basis of an executive agreement

following the Bucareli conferences. In addition to agreements regarding compensation for expropriated land and the establishment of

claims commissions, understandings were reached regarding the conditions under which the petroleum companies would operate.

The problem had not been ended, however. "When a new organic

petroleum act was passed in 1925, it contained requirements for foreign

owners of petroleum lands which the American Secretary of State, now

Frank B. Kellogg under President Coolidge, protested were in violation of the Bucareli understandings. Mexico too, however, had a new

government and it contended that the Bucareli agreements were not

binding on it.

Once again a temporary solution to the problem was found. In

1927 the Supreme Court of Mexico declared some of the controversial

provisions of the Petroleum Act unconstitutional. Moreover, that

same year the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a resolution calling

for the arbitration, if necessary, of outstanding issues with Mexico,

and Ambassador Dwight D. Morrow was sent to Mexico. Subsequently new, satisfactory amendments to the oil legislation were

enacted and the Department of State issued a statement that on this

basis future problems could be adjusted through local machinery.Zi

In 1934, the new government of President Lázaro Cárdenas brought

the question to the fore once again. A law was enacted providing

for the expropriation of private property of public utility "to satisfy

collective necessities in case of war or interior upheaval." In addition, labor laws were passed which posed heavy burdens on foreign

and numerous strikes were conducted for various benecorporations

fits.36

» Bemls, Samuel Flagg, "A Diplomatic History of the United States," New York, Henry Holt, 195«, p. 658.

u Bemls, op. clt, p. 661.

» Bemls, op. cit., p. £65,

HeinOnline - - 2 I.L.M. 1080 1963

12

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

The issue come to a head in 1938 following a strike of the petroleum

workers, when an award of a Mexican labor board called for retroactive increases in pay and other measures. The companies announced

their willingness to accept all the demands except one, but following

their refusal to accept the full award, on March 18, 1938, President

Cárdenas ordered the expropriation of their property.

The potential value of the expropriated properties was estimated

by the owners at approximately $450 million of which $200 million

was American-owned. The Mexican Government contended they

were worth a total of $262 million, with American properties less

than $50 million. In 1938 the Department of Commerce had listed

American direct investments in Mexico's petroleum industry at $69

million, and on their own books at the close of 1937 the companies

had stated their assets at about $60,247,000.39

Although one oil company reached a private settlement, the others

turned over their claims to the United States.

On November 19, 1941, the State Department announced an

exchange of notes which encompassed the settlement of expropriated

petroleum properties. A mixed commission of experts, one from

each Government, was to determine the just compensation to be paid

the American owners for their properties and rights and interests.

Meanwhile, Mexico was to make a cash deposit of $9 million to be

paid to the affected American companies.

On April 17, 1942, the mixed commission submitted their report.

It stated:

Expropriation, and the exercise of the right of eminent domain, under the

respective constitutions and lavra of Mexico and the United States, are a recognized

feature of the sovereignty of all states.

A sum of $23,995,991 was awarded to the United States, one-third

of the balance due to be paid on July 1, 1942, and the balance in

five equal annual installments at 3 percent interest.

IH. EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY SINCE WORLD

WAR II

Since the end of the Second World War, the problem of expropriation has increased according to almost any measure. Expropriations

have become more frequent; more countries have undertaken them;

more American property holders have been affected.

(A) COMMUNIST COUNTRIES

The most widespread expropriations have occurred in the countries

which adopted communism. Within a few years after the end of the

'war sweeping nationalizations àad been carried out in the Eastern

European countries and American-owned property or investments of

various kinds had been expropriated with little regard for the payment

of compensation. The pattern of action followed by the United States

was to attempt to secure a lump sum from the expropriating nations

from which claims could be paid, or to establish a claims fund from

» Bemls, S. F., "Latin American Policy of toe United States," New York, H—'court, Brace & Co., 1943,

p. 347.

HeinOnline -- 2 I.L.M. 1081 1963

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

13

the vested assets of the expropriating nation in this country.37 In

the case of Communist China and Cuba, with whom the United

States does not have diplomatic relations, the matter is being held

in abeyance pending a propitious time for negotiations.

Yugoslavia

In Yugoslavia public ownership was already widespread in 1940.

By tthe Nationalization Act of December 5, 1946, however, the

process of socialization of industry was completed, bringing into

Government ownership virtually all enterprises m important branches

of industry, wholesale trade, banking,- and transportation. This law

covered foreign-owned firms, too, and stipulated that former owners

were to be indemnified in Government bonds or, in some instances,

cash.38

Yugoslavia became the first country after the war to conclude a

lump-sum agreement providing compensation to American nationals

for losses resulting from nationalization of property. Under an

agreement of July 19, 1948, Yugoslavia paid the United States the

sum of S17 million in.full settlement of the claims of the United States

against Yugoslavia, including all claims of U.S. nationals springing

from nationalization of their property since September 1, 1939. In

return the United States agreed to release Yugoslavian blocked assets

in the United States. To carry out the agreement, Congress enacted

the International Claims Settlement Act of 1949 (Public Law 81-455,

Mar. 10, 1950) establishing a three-member International Claims

Commission to adjudicate claims within the terms of the agreement

and similar claims which might be the subject of future agreement

with another country. Dunng the filing period from June 30 to

December 30,1951,1,556 claims were asserted totaling $149,344,249.70.

The program was completed on December 31, 1954, with 876 awards

made totaling $18,817,904.89. Of this approximately 91 percent was

covered by the fund.

On December 26, 1958, Yugoslavia passed another nationalization

law under which urban dwellings, business premises, and underdeveloped building lots were taken, including U.S.-owned property.

In 1962 the United States and Yugoslavia agreed to negotiate on the

settlement of claims arising under, this law or other measures of the

Yugoslav Government since the 1948 settlement.

Poland

Nationalization of a substantial part of the Polish economy was

provided for in an act of January 3, 1946. This act also provided

for compensation to the owners of nationalized enterprises in the form

of bonds, or, in a few cases, cash or goods.

Subsequently the United States and Poland entered negotiations

concerning the compensation of US. nationals who had been affected,

and^on December 27, 1946, the two countries reached an agreement

setting forth the basic principles governing the settlement of claims.

" Much of tbe background Information In this section bas been taken from: U.S. Congress, H. Doc. 67,

83d Cong., 1st sess., transmitting tbe supplementary report of tbe War Claims Commission on "War

Claims Arising Out of World War II," Jan. 16,1963, and "Settlement of Claims," by tbe U.S. Foreign

Claims Settlement Commission of tbe United States and its predecessors from Sept. 14,1949, to Mar. 31,

1966, U.S. Government Printing Office, June 15,1966; also U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign

Relations, staff memorandum on claims programs administered by t i e Foreign Claims Settlement Commission under tbe International Claims Settlement Act of 1949, as amended, committee print, March 1963.

" Xeroer, Robert J., editor, "Yugoslavia," Berkeley, University of California Press, 1949, p. 421.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1082

1963

1083

14

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

The agreement provided for a Polish American Mixed Commission

to decide matters in dispute and an umpire to settle questions on

which the national representatives could not agree. However,

following these negotiations, a new regime assumed control in Poland

and no settlements were effected nor was a final agreement signed.

The negotiations, broken up in 1947, were not resumed until 1957.

On July 16, 1960, after almost 3 years of negotiations, Poland

and the United States signed an agreement whereby Poland agreed to

pay $40 million over a 20-year period in full settlement of all claims

of U.S. nationals on account of nationalization or other taking of

property in Poland. The payment of the $40 million was to be made

in 20 annual installments of $2 million each, beginning on January

10, 1961. This amoimt was to cover claims of U.S. citizens whose

property or lights and interest in property were nationalized or otherwise taken by the Government of Poland or .appropriated or limited

and restricted in their use or enjoyment under Polish Government

measures, plus debts owed to American citizens by nationalized or

confiscated enterprises. A total of 9,878 claims were asserted during

the filing period, amounting to $680,421,639. The making of awards

on these claims is still in process.

Czechoslovakia

In Czechoslovakia nationalization was accomplished by four decrees

of the President dated October 24,1945. Later, pursuant to the new

constitution of May 9, 1948, a new series of laws were passed by the

National Assembly which practically abolished private industry in

that country.

The decrees provided for payment of compensation with certain

exceptions for the most part in Government bonds but in a few cases

in cash or other values.

In January 1946 Czechoslovakia announced that it would negotiate

directly with the governments of the foreign nationals who had invested in nationalized enterprises and in 1948 a mission came to the

United States for the purpose of resolving the dispute over property

of Americans nationalized in Czechoslovakia. However, the negotiations were discontinued after a member of the mission resigned and

requested and received the right of asylum in the United States.

In November 1955 the Czechoslovak Government agreed to reopen

negotiations. Since that time there has been some progress in narrowing the position of the two Governments, but so far there has been no

agreement. Meanwhile, in 1958 a claims fund of $8,540,768.41 was

established under title IV of the International Claims Settlement Act

of 1949, from the proceeds of a steel-rolling mill sold under the Trading

With the Enemy Act after the Communist coup 'in Czechoslovakia.

When the program was completed on September 15, 1962, 2,630

awards had been made, totaling $113,645,205.41, of which 5.3 percent

was paid.

Bulgaria

In the Balkan countries of Hungary, Kumania, and Bulgaria, most

of the nationalization programs affecting .American property were

enacted slightly more than a year after peace treaties with the United

H e i n O n l i n e - - 2 I . L . M . 1083 1963

1084

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

15

States had been signed on February 10, 1947. However, provisions

in the treaties relating to the vesting of assets in the United States

formed the basis on which claims funds were later established under

title III oí the International Claims Settlement Act of 1949 (Public

Law 84-285, approved Aug. 9, 1955).

In Bulgaria, general nationalization of most of the economic resources was accomplished by a decree of the National Assembly on

December 23, 1947. Compensation in the form of interest-bearing

bonds to owners of nationalized enterprises, except in certain cases,

was provided for in the law.

The agreement between the United States and Bulgaria concerning

compensation for American property holders affected by the takings

was not signed until July 2, 1963. However, a claims fund for nationalization and war damage claims, amounting to $2,613,325.59,

was established out of vested assets under the International Claims

Settlement Act. When the Bulgarian claims program was completed on August 9, 1955, 217 awards had been made to claimants,

totaling $4,685,187, but this included both war damage and nationalization claims. Of this approximately 50 percent was paid

from the fund. The agreement of July 2,1963, provides for the settlement on a lump-sum basis of claims of U.S. nationals arising out of

war damage, nationalization of property, and financial debts as described in article I.

The lump-sum settlement of $3,543,398 includes $3,143,398 in assets of the Bulgarian Government and Bulgarian corporations which

were blocked in the United States during the Second World War and

$400,000 which is to be paid by the Bulgarian Government to the

U.S. Government in two mstauments, on July 1, 1964, and July 1,

1965.

Hungary

Hungary undertook nationalization more gradually, beginning as

early as 1945 and accelerating it in 1946 through a law which exempted U.S. citizens. In May 1948, however, aU industrial, mining,

electrical, metallurgical, and transportation facilities located m

Hungary and employing more than 100 persons were nationalized.

Although the various nationalization laws provided that compensation was to be prescribed by separate acts of Parliament, no compensation has been paid to US. nationals. A Hungarian claims fund

of $1,653,647.09 was established from vested assets in the United

States to cover claims resulting from both war damage and nationalization. When the claims program was completed on August 9, 1959,

1,153 awards had been made for $58,181,408, but these figures include

claims for war damage as well as nationalization.

Rumania

The basis for Rumania's nationalization of private property was its

constitution of April 13, 1948. Although the subsequent law implementing nationalization provided that owners and stockholders of

nationalized enterprises were to be compensated by securities redeemed from the net profits of the new national enterprises, the

American owners were not compensated at the time.

20-821—03

4

H e i n O n l i n e - - 2 I . L . M . 1084 1963

1085

16

EXPROPRIATION OF AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

In 1955 a claims fund of $20,057,346 was established out of vested

assets and when the claims program was completed on August 9, 1959,

498 awards totaling $60,011,348 had been made for both war damage

and nationalization claims, of which amount approximately 30 percent

was paid.

In addition, on March 30, 1960, Rumania and the United States

signed a lump-sum agreement under which Rumania agreed to pay the

United States an additional $2.5 million in five installments between

July 1,1960, and July 1,1964, as afinalsettlement of total U.S. claims

against Rumania.

Communist China

As of 1949, the value of U.S. investments in China were estimated

at $56 million, not including various schools and universities, such as

Peiping Union Medical College, St. John's University,

and Yale in

China, or U.S. embassy and consular property.38 After the Communist takeover, all of this was taken. First the schools were nationalized. Then a number of U.S. firms were forced out of business by an

increasing number of restrictions and punitive taxes. After the outbreak of the Korean war, by a decree of December 29, 1950, the

Chinese Communist government assumed control of all U.S. property,

whether owned by the Government or private citizens.

The United States has never established diplomatic relations with

Communist China, and no settlement has been made. However, during the Korean war the assets located in the United States of all residents of mainland China were blocked and in 1954 the United States

delivered a diplomatic notetoTaipeh listing the properties in China belonging to the U.S. Government. In addition,listshavebeen compiled

of the losses of American firms, and statements of claims have been

registered by private citizens with the Department of State.

Cuba

Following the taking over of the Cuban Government by Fidel Castro

at the beginning of 1959, American property in Cuba was rapidly subjected to "intervention" (a term used to denote the taking over by

the Cuban Government of the management of an enterprise), harassment, expropriation, and confiscation. Eventually all but a relatively small amount of U.S.-owned property was taken. Official estimates of the total value of U.S. property lost now stand at $1% billion.40

As far as is known by the Department of State, no compensation was

made in any instance and the government bonds by which compensation was to be made under some of the Cuban laws have not even

been printed.

Intervention of U.S.-owned firms began with the Cuban Telephone

Co. on March 4,1959, and interference of various kinds with Americanowned property steadily increased. On May 17, 1959, on agrarian

reform law was enacted which provided for the taking of agricultural

properties with payment to be made in 20-year bonds at 4}£ percent

interest. Soon after the passage of the agrarian reform law, the

United States expressed its concern over the adequacy of the provisions for compensation, although it also stated that it recognized

the right of a state to expropriate property for public purposes,

» information from the Department of State.

io Information from the Department of State.

HeinOnline - - 2 I.L.M. 1085 1963

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

17

coupled with the obligation to make prompt, adequate, and effective

compensation.41

On October 26,1959, the Cuban Government passed a law imposing

confiscatory taxes upon the nickel plant owned by the United States,

and other restrictive or harassing measures were applied to U.S.

enterprises, such as requiring the reregistration of all mining concessions.

The pace of interventions quickened and sugar owners began to

lose their properties. On January 11, 1960, the United States protested, against actions of Cuba which it contended were violating the

basic rights of ownership of U.S. citizens. It said land and buildings

of U.S. citizens were being seized and occupied without court orders or

written authorizations, that equipment and cattle were being seized or

moved, timber was bemg cut, and pastures plowed under, often without taking inventories or giving receipts or any indication that payment of compensation would be offered.42 Cuba replied on February

14,1960, that where property had been occupied steps were being taken

for its appraisal, and that if the United States considered that Cuban

laws had been violated, U.S. nationals had the right to appeal through

appropriate channels.

Next the oil companies were hit. On May 17, 1960, the National

Bank of Cuba informed the U.S. oil companies in Cuba that each of

them would be required to purchase 300,000 tons of Russian petroleum

during the balance of 1960. Later the oil refineries were seized on the

grounds that they had violated the law in refusing to refine Soviet

petroleum. This action was protested by the United States on July 5.

1960, in a note which stated that the actions were "arbitrary and

inequitable, without authority under Cuban

law, and contrary to

commitments made to these companies."43

On July 6, 1960t the Cuban Government passed a law which

authorized the nationalization of U.S.-owned property generally.

The law authorized payment to be made from a fund to be derived

from the receipts from annual purchases of Cuban sugar by the

United States over 3 million tons, at the price of at least 5.75 cents a

pound, payment to be in 30-year bonds at 2 percent interest. On

the same day, the United States reduced the Cuban sugar quota by

700,000 tons, President Eisenhower stating that the United States

would fail in its obligations to its own people if it did not take steps

to reduce its "reliance for a major food product upon a nation which

has embarked upon a deliberate policy of hostility toward the United

States." «

The nationalization law was protested by the United States on

July 16, 1960, as discriminatory (because it was specifically limited

to property owned by U.S. nationals), arbitrary (because it was

admittedly enacted in retaliation to actions taken by the United

States to assure its sugar supply), and confiscatory (because it failed

to meet minimum criteria necessary to assure prompt, adequate, and

effective compensation, and prohibited any form of judicial or administrative appeal from the decisions of the expropriating authorities).45

«

o

«

«

«

Note of June 11,1969, Department of State Bulletin, June 29,1969, pp. 968-959.

Statement of Jon. 11,1969, Department of State Bulletin, Feb. 1,1960, p. 168.

Note of July 6.1960, Department of State Bulletin, July 26,1960, p. Ulf

Statement of July 6,1960, Department of State Bulletin, July 25,- I960, p. 140.

Note of July 16, I960, Depsrtment-of State Bulletin, Aug. 1, I960 , p. 171.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1086

1963

1087

18

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

When the Castro government sought to justify its actions on the

grounds that the United States had committed economic aggression in

reducing Cuba's sugar quota, the United States said that about onehalf of the investments had been seized before any change in the

quota was made.

On September 17,1960, three American-owned banks were nationalized, 48against which the United States protested on September 29,

I960. Next the nickel plant owned by the U.S. Government was

intervened, and on October 24, 1960, it was among 166 properties

which were nationalized. This was protested by the United States on

November 19, 1960. Meanwhile, Cuba was taking additional

hostile actions toward the United States while establishing closer

relations with the Communist bloc and on January 3, 1961, after a

demand that the U.S. Embassy be reduced to 11 officials, the United

States terminated diplomatic and consular relations with Cuba.

Thus far some 90 documented statements of claims have been filed

•jrith the State Department, which are being retained until an opportune tune to submit them.

On July 8, 1963, the United States froze all Cuban assets in the

United States, estimated to total some $30 million. This includes

assets owned by the Cuban Government and individual Cubans

residing on the island but not the property of Cuban exiles residing

abroad. Part of these assets are already under litigation, being

claimed as compensation by some of the Americans who had property

taken by the Castro government.

(B) EXPROPRIATION IN NON-COMMUNIST COUNTRIES

Not all of the expropriations since the end of the Second World

War have occurred m Communist countries, however. In addition

to the continuing occasional expropriations of land by Mexico, the

following ore the major other expropriations of American-owned

property which have occurred.

Bolivia, 1952

On October 31, 1952, the Government of Bolivia issued a decree

nationalizing the mines and other properties belonging to the three

largest companies—Patino, Aramayo, and Hochschild. Three percent interest was to be paid on the capital value of the nationalized

property pending a final settlement. Although none of the companies

was incorporated in the United States, the Patino company was

partially owned by the U.S. stockholders and the United States has

made representations in behalf of these stockholders. In addition,

it encouraged direct 47

negotiations between the companies and the

Bolivian Government.

Under an interim agreement of June 1953, Bolivia agreed to make

annual payments to the companies based on the price of tin. Payments to the three companies totaling about $20 million were made

in the next 8 years. In August 1961 Bolivia declared a moratorium

on the payments until agreement could be reached with the companies

on the total amount to be paid and pending an attempt to rehabilitate

the mines. In January 1962, representatives of the Patino company

M Nate of Sept. 29, I960; Department of State Bulletin, Oct. 17,1960, p. 601.

4) Information from the Department of State.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1087

1963

1088

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

19

and the Bolivian corporation running the mines agreed to further

compensation of $4.2 million beginning January 1, 1965, at the end

of the moratorium. This agreement has not yet gone into effect.

Guatemala, 195S

On June 19, 1952, an agrarian reform law was enacted by the

Arbenz government which had come to power in Guatemala the

previous year and was widely recognized as Communist influenced.

Subsequently on March 5, 1953, Guatemala expropriated 234,000

acres of land belonging to the United Fruit Co. Compensation was

proffered the company in tbe form of Guatemalan Government 3percent "agrarian bonds" maturing in 25 years and in a face value

equivalent to the tax value of the land as recorded on May 9, 1952.

The United States protested that the method of fixing of the amount

of the bonds did not bear the slightest resemblance to just evaluation,

especially

in the light of tax evaluation procedures followed in this

case.48

The threat of Communist penetration in the Western Hemisphere

elevated the events occurring in Guatemala during this period to a

crisis status. However, this threat diminished when a new government took power. Similarly, the expropriation problem ended because

it was rescmded by the new government.

Suez Canal, 1956

On July 26, 1956, shortly after the United States and United

Kingdom withdrew offers to assist in building the Aswan Dam,

President Nasser of Egypt issued a decree nationalizing the Universal

Co. of the Suez Maritime Canal, largely owned by the British Government and private stockholders in France, but with some U.S. stock

ownership. The decree stated' that stockholders would be compensated in accordance with the value of the shares in the Paris Stock

Exchange on the day before the nationalization with 4payment made

after all assets and properties had been delivered. ' Britain and

France immediately protested, and a serious international crisis

ensued which involved hostilities between Egypt and Britain, France,

and Israel as well as United Nations police action.

The United States took the position that the Egyptian action went

far beyond a question of nationalization since80it involved a vital

waterway which was international in character. Subsequently the

United States took an active part in trying to devise a peaceful solution

to the problem and, when hostilities did occur, to restore peace.

With the International Bank affording its good offices between the

Egyptian Government and the Suez stockholders, on July 13, 1958,

an agreement was signed which provided for a payment by the United

Arab Republic to the stockholders of 4128,300,000 Egyptian pounds,

plus all external assets of the company.

Argentina, 1968

On July 7j 1958, a subsidiary of the American & Foreign Power Co.

was expropriated by the municipal government of Toberia in Buenos

Aires Province. With the United States affording its good offices,

>> Note of Aug. 28,1953: Department of State Bulletin, Sept. 14,1963, p.357.

" U.S. Department of State, "The Suez Canal Problem, July 26 to Sept, 22,1956," p. 31.

" Ibid., p. 38.

» Text of "Heads of Agreement," Department of State Bulletin, June 30,1958, p. 1097.

HeinOnline

--

2 I.L.M.

1088

1963

20

EXPROPRIATION OP AMERICAN-OWNED PROPERTY

a settlement was effected through local remedies. The settlement,

made November 28, 1958, between Argentina and the company, also

covered properties previously expropriated, seized, or intervened by

local governments in Argentina. It provided that all American &

Foreign Power electric facilities in Argentina would be transferred to