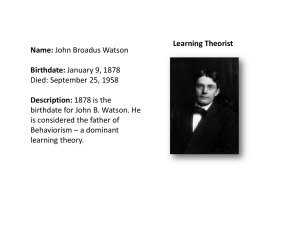

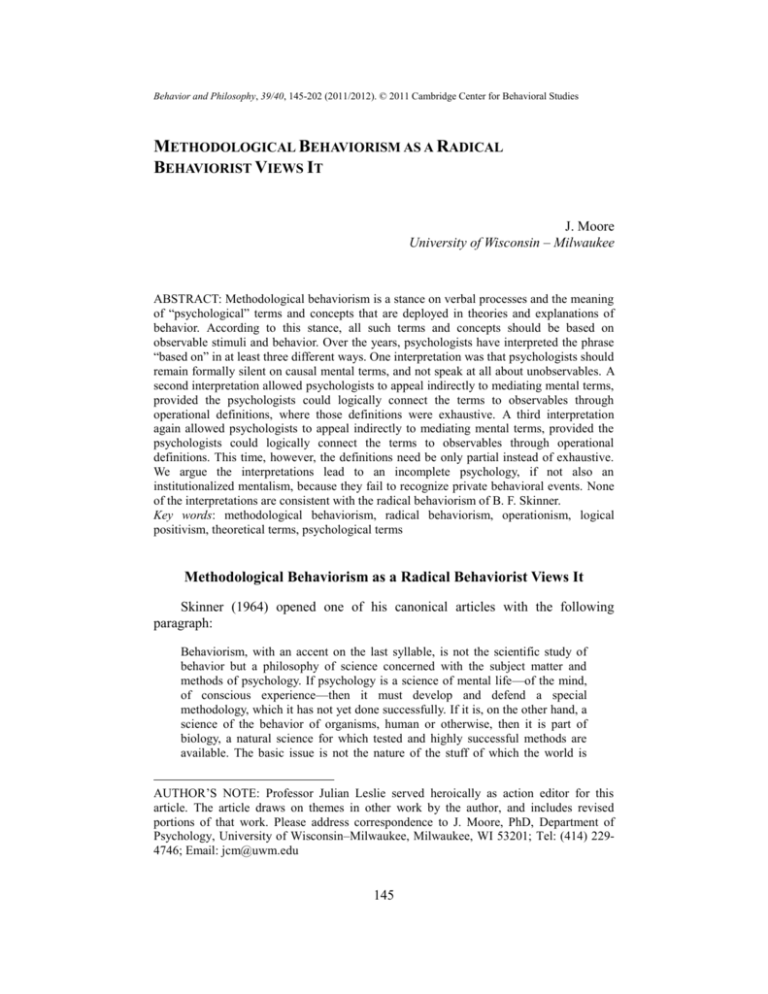

methodological behaviorism as a radical

advertisement