Conducting criminological research in a hospital: The results of two

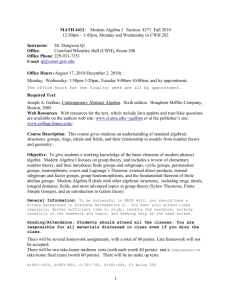

advertisement

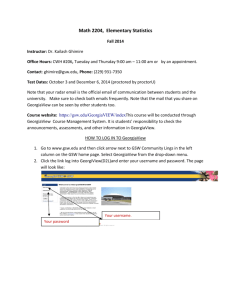

CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 75 Research Note * Conducting Criminological Research in a Hospital: The Results of Two Exploratory Studies and Implications for Prevention Connie Hassett-Walker Douglas J. Boyle Violence Institute of New Jersey University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey * Abstract This article discusses the results of two exploratory studies using hospital data on intentional assault injury. Study #1 was a two-year gunshot wound (GSW) surveillance effort (N = 920). A map of the EMS dispatch addresses revealed that certain neighborhoods were “hotspots” for gun violence. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that poverty, vacant housing and rental housing were significant predictors of a neighborhood’s GSW rate. Study #2 involved interviews with assaulted patients (N = 30). More than half of the sample had been incarcerated, which is striking considering their young age (i.e., 21 years old and younger). Prevention implications of both studies are discussed. JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2007 © 2007 Justice Research and Statistics Association 76 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY Criminologists use a variety of data sets and types, each with its own strengths and weaknesses—including the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR); the UCR’s Supplemental Homicide Reports (SHR) and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS); the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS); and the Monitoring the Future Survey of students’ drug use, to list a few examples (Maxfield, 1999). Consulting different data sources can lead to diverse conclusions about whether crime is increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable (O’Brien, 1996; Boggess & Bound, 1997). The UCR are valid measures of serious crime that is reported to the police, particularly for homicide, burglary, robbery, and motor vehicle theft (Gove, Hughes, & Geerken, 1985). For other types of crime (e.g., aggravated assault, rape), however, the evidence is more qualified. For instance, Gove and colleagues note that many aggravated assaults—particularly those committed by friends and family—are not recorded in the UCR. Critics of arrest data note that they likely underestimate the true incidence of crime, as many acts are undetected and unreported to police, thereby resulting in no arrest (Jenson & Howard, 1999). Victimization survey data such as the NCVS are useful for measuring unreported activity, that is, the “dark figure” of crime (Maxfield, 1999). Because victimization surveys have revealed that most crimes are not reported to the police, these findings have called into question the validity of arrest data (Gove et al., 1985). Victimization surveys are not without problems. For instance, people may be reluctant to report being victimized by someone they know, such as a family member or close friend (Strom, 2000; Cook, 1985). In addition, because it focuses on victimization of individuals living in households, the NCVS would likely miss incidents involving the homeless (for instance) as well as “victimless” crimes (e.g., prostitution, gambling) (Maxfield, 1999). Other survey instruments, such as the Monitoring the Future Survey and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), ask youth to self-report their drug use, delinquency, and non-fatal violent behavior (e.g., fighting), among other things (Jenson & Howard, 1999). A disadvantage of self-report data is that they tend to underestimate socially unacceptable behaviors and traits (e.g., deviant behaviors, racial prejudice) (Singleton & Straits, 2005). In addition, Gove and colleagues (1985) note that self-report studies include a high rate of non-serious crime. A search of criminal justice abstracts found few studies using medical and public health data on intentional assault injury, suggesting these data are not widely utilized by criminologists. While some research involving hospital-based injury surveillance has been conducted (e.g., Graitcer, 1987; Hutson, Anglin, & Pratts, 1994; Litaker, 1996; Wilt & Gabrel, 1998; Gotsch, Annest, Mercy, & Ryan, 2001), the results of such efforts have been published largely in public health and medical journals. Exceptions include the work of Rand (1997); Strom (2000); Decker, Curry, Catalano, Watkins, and Green (2005); and most recently Cohen and Lynch (2007). The present article discusses the results of two exploratory studies that use hospital data on intentional assault injury. Study #1 is a two-year, gunshot wound CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 77 (GSW) surveillance effort (N = 920) conducted in a level one Trauma Center located in Newark, New Jersey, a mid-size urban center. Similar to the methodology adopted by Strom (2000) and Rand (1997), the data used in Study #1 were extracted from patients’ medical charts and medical histories, to record information such as prior violent injuries. In other words, the data extracted are based on medical staff notations regarding prior violent injuries (for instance), rather than patient self-report. This is an advantage of working with hospital data on assault—despite a patient’s potential reluctance to discuss their victimization, concrete evidence of a crime exists (e.g., bullet holes or fragments present in the body). In addition, the geographic locations of the shootings (i.e., the EMS patient retrieval address) are included in map form, a unique contribution for studies using hospital data. Implications for prevention planning at the neighborhood level (e.g., city housing policies to alleviate concentrated poverty and vacant housing) are discussed. Study #2 (N = 30) was conducted subsequent to the first study, in the same facility, and involved more detailed interviews with assaulted adolescent and young adult patients. The results are presented, followed by a discussion of the next steps to plan a re-injury prevention program with this population. * Description of Present Studies Setting The University Hospital Trauma Center (hereafter Trauma Center), where both studies took place, is located in Newark, NJ, which has a population of just over 273,000 residents (U.S. Census, 2000). Of the top 15 urban centers profiled by the State Police for 2005, Newark had the highest crime index and the largest number of violent crimes of any city statewide (State of New Jersey, Division of State Police, 2006). The Trauma Center is a level one trauma treatment facility that serves more than one million individuals statewide. Within its catchment area, more than 90% of violence victims with injuries requiring hospitalization receive treatment at the Trauma Center (Lavery et al., 1999). The studies to be described grew out of an earlier effort to study and prevent violence in the greater Newark area (Boyle & Hassett-Walker, in press). That initiative was broader in scope, and involved collecting data on all assault-related visits at six local hospitals providing emergency medical care. Description of the Studies1 Study #1: The study’s authors collected data on non–self-inflicted GSW victims treated at the Trauma Center and/or the hospital’s emergency room from 1 Both studies had prior approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board. 78 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2005. Medical students, as well as the project’s data coordinator, reviewed daily the medical charts of GSW patients. Data extracted from the medical records included patient demographics (i.e., gender, age, race/ethnicity); seriousness of injury (e.g., whether the patient was treated and released, admitted to the hospital, or died); any past medical treatment for intentional assault injuries; any evidence of current or past criminal involvement; and the address at which the ambulance (i.e., EMS) retrieved the patient. Study #2: The second study developed out of recognition that data gathered only from patient medical records (i.e., Study #1) would provide better information about gun violence at the city level, particularly the spatial distribution of GSWs. However, data were still needed about individual-level, contextual factors related to assault. As a result, in Study #2 semi-structured interviews were conducted with consenting patients 13 to 21 years of age, who received treatment for an intentional assault-related injury (e.g., GSW, stabbing, assaulted with fists). The interviews were conducted from September 2005 through September 2006. The interviewer, a licensed clinical social worker, asked patients about their education, work history, and family environment, including cohabitation with younger siblings and other younger relatives who were likely affected by the assault. Patients were also asked about the context for the assault, and any role the patient may have played in the assault event; alcohol and drug use; violence in the patient’s residential neighborhood; and past involvement in the criminal justice system. A main goal of Study #2 was to use the data gathered to plan an intervention to prevent reinjury. Moscovitz, Degutis, Bruno, & Schriver (1997) note that 30% of individuals injured through interpersonal violence sustain subsequent violence-related injuries. There are advantages to establishing a violence intervention within a hospital setting, including a prolonged period of providerpatient contact and the resulting potential to form patient-caregiver bonds (Hausman, Prothrow-Stith, & Spivak, 1995). Although the field is relatively new, some hospital-based violence interventions have evidence to support their effectiveness (e.g., Zun, Downey, & Rosen, 2006; Cooper, Eslinger, & Stolley, 2006; Becker, Hall, Ursic, Jain, & Calhoun, 2004). * Statistical Analyses and Variables Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 14.0 software for Windows. The hotspots map shown in Figure 1 was generated using Arcview Spatial Analyst 9.1 geographical mapping software, and hierarchical nearest neighbor clustering in CrimeStat software. A one-tailed probability level of .05 was selected. A hotspot is an area where residents have a higher than average risk of being victimized (Eck, Chainey, Cameron, Leitner, & Wilson, 2005). The results of Study #1 are presented first, and include GSW patients’ prior assault injuries and evidence of criminal activity. We also examine socio-structural CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 79 predictors of a neighborhood’s GSW rate per 1,000 residents using both correlational analysis and hierarchical regression. Statistical analysis revealed a positive skew in the rate of GSW injury by block group, and thus we transformed the rate using the logarithmic function in SPSS. The socio-structural variables were taken from the U.S. Census 2000, at the level of patients’ residential block group.2 These were: • concentration of poverty (i.e., the ratio of the population with income in 1999 below poverty level to the population for whom poverty status is determined); • percentage of vacant housing units; and • percentage of rental housing units. The two latter variables—percentage of vacant housing and rental housing units—are proxy indicators of residential mobility, an element of social disorganization theory (Shaw & McKay, 1942; Bursik, 1988; Sampson & Groves, 1989; Sampson & Wilson, 1995). Past research has shown that residential instability and low rates of home ownership correlate with many problem behaviors (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). * Results of Study #1 Patients’ Prior Assault Injuries As shown in Table 1, around 40% of GSW patients sought previous medical attention for some illness or injury prior to treatment for their GSW injury. Nearly 15% of patients had previously received Trauma Center medical treatment specifically for a prior assault-related injury (e.g., being previously shot and/or stabbed). This percentage increases slightly to 20% when patients’ prior assault injury treatment at other hospitals, as well as the Trauma Center, is considered. In other words, nearly one in five GSW patients had some notation— either in their medical chart (e.g., existing bullet fragments from a previous shooting may have been found in the patient’s body) or in one of the hospital’s databases—about having sustained a prior assault-related injury. Analyses using other criminal justice datasets also find support for the idea of repeat victimization, including the National Youth Survey (NYS; Lauritsen & Davis Quinet, 1995); the British Crime Survey (Ellingworth, Hope, Osborn, Trickett, & Pease, 1997); and the NCVS (Tseloni & Pease, 2004). 2 A subdivision of a census tract (or, prior to 2000, a block numbering area), a block group is the smallest geographic unit for which the Census Bureau tabulates sample data. (See http://www.metrokc.gov/gis/mapportal/CV_glossary.htm#cbg and also http: //www.census.gov/geo/www/cob/bg_metadata.html.) 80 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY * Table 1 Study #1: Patients’ Prior Injury and Criminal Behavior (N = 920) Patient History Prior Trauma Center (TC) visits, any reasona Prior TC assault-related visits Any priorb Current or prior criminal involvement Patients (n) 364 134 183 72 Percent 39.6% 14.6 19.9 7.8 GSW patients had past usage of University Hospital for a variety of reasons, including toothaches, kidney stones, sexually transmitted diseases, fever, pregnancy-related visits, alcohol and drug overdoses, and motor vehicle crashes. a Any prior includes a patient’s prior treatment at the Trauma Center (n = 134) as well as at other hospitals (n = 49) for assault-related injury. b Patients’ Prior Criminal Activity Notations were found in nearly 8% of GSW patients’ medical charts indicating they had current or past criminal involvement (see Table 1). This figure is most likely an underestimate—underscored in particular by the findings from Study #2, discussed shortly—since the Trauma Center staff is not required to document this information, as it is non-medical in nature. The following are some examples of crime-related notations extracted from the GSW patients’ charts: (a) discharged into custody of police; (b) attempted robbery; (c) during prior Trauma Center visit, patient was a detainee at county juvenile detention; (d) inmate identification found on patient; (e) patient is on house arrest, parole officers stop by to see patient; and (f) patient pulled gun on police and was shot. It should be noted that these are medical staff notations with regard to patient processing rather than the patients’ self-report about their behavior. In at least one instance, both the criminal and the police officer were wounded by gunfire during the same incident, and both ended up as patients receiving treatment at the Trauma Center. Other criminological research similarly suggests that victims and offenders are not mutually exclusive groups (e.g., Rapp-Paglicci & Wodarski, 2000; Lauritsen & Davis Quinet, 1995; Lauritsen, Laub, & Sampson, 1992; Jenson & Brownfield, 1986; Singer, 1981). Spatial and Time Distribution of GSWs Figure 1 illustrates the hotspots of GSWs during the two-year study period. The map was created using addresses of EMS dispatch locations, which were CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 81 only available for patients transported to the Trauma Center via ambulance. As seen in Figure 1, the data’s geographical distribution reveals that certain areas of the city were significantly more likely to produce GSW victims—including those neighborhoods located near the Trauma Center (i.e., at University Hospital). Other criminological research also shows that crime clusters geographically (e.g., Shaw & McKay, 1942; Land, McCall, & Cohen, 1990; National Research Council, 2001). * Figure 1 GIS Hotspot Map of GSWs Based on EMS Dispatch Location in Newark, East Orange, and Irvington (1/1/04 - 12/31/05) The distribution of GSW victims by time (Figure 2) reveals that the late night/early morning hours are peak times for local gun violence. An analysis of the distribution of GSW victims by day of the week (not shown in table or figure format) reveals that Sundays and Mondays are peak days for gun violence: 39% of GSW patients were admitted on those two days. An additional 15% of patients were admitted on Saturdays. 82 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY * Figure 2 Distribution of Gunshot Victims by Time of Day 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 2 3 AM Noon 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PM Socio-Structural Characteristics of GSW Hotspot Neighborhoods In an effort to ascertain what neighborhood-level factors might be related to the GSW hotspots, we conducted correlational and regression analyses using socio-structural factors from the U.S. Census. Table 2 presents the Pearson’s correlations between the log of a block group’s GSW rate per 1,000 residents and the three socio-structural indicators described earlier (i.e., poverty concentration, percentage of vacant housing units, and percentage of rental housing units), which were operationalized from social disorganization theory. The correlational analyses revealed significant, positive relationships between a neighborhood’s GSW rate and its concentrated poverty and percentage of vacant housing units, but not the percentage of rental housing units. * Table 2 Correlation of GSW Rate (log) per 1,000 Residents by Block Group and Socio-Structural Indicators (n = 193) GSW Rate GSW Rate Poverty Concentration Percentage of Vacant Housing Units Percentage of Rental Housing Units *p ≤ .01 .38 * .21 * .03 Poverty Concentration .24 * .50 * Percentage of Vacant Housing Units .17 * CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 83 The hierarchical regression is shown in Table 3. We decided to enter poverty concentration first, as it was the strongest predictor in the correlational analyses. Because rental housing was non-significant in the correlational analyses, we excluded it from the regression. The overall model is significant, explaining 16% of the variance in the GSW rate by block group. Significant at the p ≤ .05 level, both poverty and vacant housing influence the GSW rate in the theoretically expected direction, although poverty concentration is the stronger predictor. These results are consistent with the findings of prior research (Boyle & Hassett-Walker, in press). * Table 3 Socio-Structural Predictors of GSW Rate (log) per 1,000 Residents by Block Group (n=193) Predictor Beta ΔF ΔR2 Sig. Poverty concentration Vacant housing units Constant .35 .14 32.14 4.62 .14 .02 .00 .03 .36 R2 Adjusted R2 DF F P .16 .16 2 18.69 .00 Comparing GSW and Arrest Data Table 4 shows how the GSW data compare with State Police arrest data collected during the same time period. While it is not possible to assess a trend from only two years’ worth of data, it should be noted that both the GSW and Newark arrest data increased during the 2004–2005 period. Arrests also increased slightly from 2004–2005 in Irvington (for murder), but not East Orange (for either murder or aggravated assault). These data reflect the overall crime situation in the state’s urban areas during the 2004–05 period. According to police data, the overall violent crime index for New Jersey’s “Urban Fifteen”3 cities increased from 15,916 (2004) to 16,657 (2005) (State of New Jersey, Division of State Police, 2006). That said, 8 of the state’s 15 urban centers had increases in the violent crime index, 6 had decreases, and one city remained virtually the same. In other words, what is seen in the GSW data reflects the state of affairs of violent crime in New Jersey’s urban centers during the same time period—a mixed bag of sorts. The three cities referenced in Table 2 – Newark, Irvington, and East Orange – are among the New Jersey “Urban Fifteen.” 3 84 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY * Table 4 Comparing Trauma Center GSW Data and Police Violent Crime Arrest Data 2004–2005 Period Year 2005 Year 2004 124 796 69 419 55 377 Police Arrest Data, Newark Arrests for murder Arrests for aggravated assault 184 2,848 98 1,441 86 1,407 Police Arrest Data, Irvington Arrests for murder Arrests for aggravated assault 54 1,243 28 618 26 625 Police Arrest Data, East Orange Arrests for murder Arrests for aggravated assault 31 975 14 470 17 505 Data Type Trauma Center Data Fatal GSW Non-fatal GSW Note. Source of police violent crime arrest data is the State of New Jersey, Division of State Police (2006) The Trauma Center GSW data and the arrest data are to some extent intertwined. For instance, some of the Newark, Irvington, and East Orange assault and homicide victims (who were attacked by the offenders reflected in the police arrest data) turn up at the Trauma Center. That said, the two datasets do not deal with identical incidents; nor are the counts intended to be exactly the same. Not all fatal GSW patients arrive at the Trauma Center, for instance; some are transported directly to the city morgue. In addition, not all homicides are committed with a firearm. Other Patient Characteristics Males (n = 854) comprise nearly 93% of GSW patients. The majority (i.e., 85%) of GSW victims in Study #1 are African American (n = 785). These results reflect other research that shows an overrepresentation by both males (e.g., Frazier, Bock, & Henretta, 1983; Broidy & Agnew, 1997; Jenson & Howard, 1999; Walklate, 2001) and African Americans (e.g., LaFree 1995, 1998; Hawkins, Laub, & Lauritsen, 1998; Harrison & Beck, 2002; Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2001) in criminal justice statistics. In addition, 4% (n = 40) of GSW patients are white. Ethnically, 9% (n = 86) of GSW patients are Hispanic. Table 5 illustrates the age groupings of the GSW victims in Study #1. Young adults 20 to 24 years of age comprise about one quarter of GSW victims, where- CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 85 as they make up less than 8% of Newark’s population (as well as the populations of Irvington and East Orange, respectively), according to the U.S. Census American Community Survey for 2005.4 * Table 5 GSW Victims by Age Range (n = 903) Years of Age Patients (n) Percent Under 15 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–44 45–54 55–64 65–74 Over 74 15 146 247 208 107 133 33 8 2 4 1.7% 16.2 27.4 23.0 11.8 14.7 3.7 0.9 0.2 0.4 Total 903 100 Note. Data on patient age are missing for 17 patients. This may be, for instance, because the patient was admitted to the emergency room unconscious, subsequently died, and no identification was found on his/her body. The GSW data regarding victim age reflect the age-victimization curve found in other criminal justice data. In 2000, individuals in their early 20s comprised 19% of murder victims nationwide (Federal Bureau of Investigations, 2001). In the 2005 NCVS data, aggravated assault rates were highest for individuals 20 to 24 years of age (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006: Table 3). By contrast, the young adult peak among the GSW victims is older than the peak teenage offending years typically described by criminologists discussing the age-crime curve (e.g., Steffensmeier, Allan, Harer, & Streifel, 1989; Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1989; Farrington, 1986). * Results of Study #2 Patients’ Prior Assault Injuries Twenty percent of interviewed assault-injured patients (n = 6) showed up in the hospital database as having received prior treatment at the Trauma Center for an assault-related injury. In addition, half (n = 15) said they had had a physical 4 The American Community Survey is a service provided by the U.S. Census. It is available online at http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html. 86 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY fight (or fights) during the past year. When asked about prior victimization, the subjects did not always perceive a previous assault in the context of being a victim. Rather, they saw themselves as an equally matched and active participant in a violent event. This finding ties in with what Fagan and Wilkinson (1998) learned from their interviews with young, inner-city males who had previously been involved in a violent event. In terms of self-conceptualization, the young men largely saw themselves as being able to hold their own in social situations, as opposed to being a punk (i.e., a weaker person, frequent victim). Evidence of Patients’ Criminal Activity Three out of four interviewed patients (n = 23) said they had been previously arrested; and 53% (n = 16) had been previously incarcerated.5 During one trip to a hospital room to obtain consent from a potential study participant, it was revealed that the victim had outstanding warrants for his arrest, and that he would be discharged from the Trauma Center to jail. Although the sample size is small, the results echo the findings of other criminal justice research (e.g., Rapp-Paglicci & Wodarski, 2000; Lauritsen & Davis Quinet, 1995; Lauritsen et al., 1992) that criminals are at risk for assault. What is particularly striking about the incarceration finding is how young the subjects are (i.e., no older than 21 years at the time of the interview). Other Patient Characteristics Ninety percent of patients interviewed in Study #2 were male (n = 27). Mean patient age was 18.3 years, although as previously noted, subjects’ age range was only 13 to 21 years as per the study design. Seventy percent of assault injury victims were African American. In their longitudinal study of adolescent risk factors, Sege, Stringham, Short, and Griffith (1999) found that adolescents who were not in school, or reported both fighting and illicit drug use, were at highest risk for violence-related injury. Many of the patients interviewed for Study #2 fit with this description. Nearly half of the sample (n = 14) were not currently in school, and had neither graduated from high school nor obtained their GED. Of the adult subjects (i.e., 18 years of age or older), only one third were employed at the time of the interview. As was mentioned earlier, half of the sample had fought physically during the prior year. Twenty percent (n = 6) of the sample indicated that they drink regularly, and more than half (n = 16) said they use drugs (mostly marijuana). Interviewed subjects had been incarcerated at both juvenile and adult detention facilities. Length of time of stay varied. One subject reported being locked up several times at the county youth house for truancy, each time staying less than a week. Another subject had spent five months at a youth house, and at the time of the interview was out on bail awaiting sentencing for drug possession and weapon-related charges. 5 CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 87 Twenty percent had used drugs shortly before the assault that led to their most recent treatment6 at the Trauma Center. Finally, 90% had witnessed violence in their community, and a quarter said they had lost friends or family to violence. In short, the interviewed patients in Study #2 seem at high risk for future violence-related injuries, and prime candidates for an intervention. * Prevention Implications Prevention Implications from Study #1: Increase Neighborhood-Level Collective Efficacy Prevention implications can be inferred from the findings of the regression analysis. The block groups with higher GSW rates tended to be poorer and have greater numbers of vacant housing units. The significance of vacant housing units as a predictor of a neighborhood’s GSW rate suggests that there may be something about an area having less collective efficacy (i.e., residents and neighbors looking out for one another, and each other’s property and children) that facilitates more gun violence occurring there (Land et al., 1990; Parker, 1989; Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls, 1997; Marciniak, 1994). By contrast, other neighborhoods may be similarly poor, but have fewer vacant apartments or buildings, and more people residing there who are willing to look out for one another (i.e., greater collective efficacy). This could lead to less gun violence in such a block group, and generally greater neighborhood-level safety. City-level housing policies that target areas with more vacant housing could potentially help lessen local gun violence. In addition, because the effect of poverty concentration was so strong, a solution might be to offer financial incentives to facilitate greater class diversity among Newark residents (i.e., working- and middle-class residents residing in the same block groups with more impoverished residents). Wilson (1987) describes this as the vertical integration of families at different socioeconomic levels, which can socially buffer against concentrated poverty. Prevention Implications from Study #2: Reinjury Prevention Planning In addition to treatment for their physical injuries, assault-injured patients also need substance abuse and mental health treatment, the latter for both preexisting conditions as well as for the trauma associated with being the victim of a violent crime. An advantage of a hospital-based intervention lies in the “teachable moment” concept; that is, life transitions such as health events that inspire That is, during the September 2005-September 2006 study period, at which point they enrolled in Study #2 6 88 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY individuals to spontaneously adopt risk-reducing behaviors (McBride, Emmons, & Lipkus, 2003). Various references to the teachable moment idea show up in medical and public health literature (e.g., Mitka, 1998; Stevens, Severson, Lichtenstein, Little, & Leben, 1995). Offering an intervention to patients admitted for a violent injury may help reach a population not accessible in other settings, and one that is ready to change. A common element of hospital-based reinjury prevention programs with evidence of effectiveness (i.e., Caught in the Crossfire, Becker et al., 2004; the Violence Intervention Program (VIP), Cooper et al., 2006; and an “ED-based violence prevention program,” Zun et al., 2006, p. 12) is heavy staff involvement with the injured youth. In the case of the VIP (Cooper et al., 2006), for instance, team members met weekly for group encounter sessions. Teams consisted of two social workers and two case workers; a program manager; probation and parole agents; and staff from myriad hospital departments. Zun and colleagues (2006) note that the case managers met with participating youth weekly for the first two months, every other week for the second two months, and monthly thereafter. Among the next steps for Study #2 is to seek funding to hire a licensed clinical social worker to coordinate the planning and start-up of an intervention. A multi-pronged approach will likely be used, including reaching out to patients treated through the Trauma Center, as well as their families, particularly younger siblings, cousins, and other youth who cohabitate with the patient. (Seventythree percent of interviewed patients indicated that they live with and/or have younger siblings or cousins; 13% had children of their own.) In addition, a prevention and/or intervention program may be offered in schools located in the high-violence neighborhood(s) identified through mapping, similar to that used in Study #1. An interesting finding from the evaluation of the VIP (Cooper et al., 2006) is that the treatment participants may have been intrinsically motivated to participate in the intervention, as many of them had just survived a second or third life-threatening assault. They may have believed their odds of survival were declining. The fact of their older age (i.e., 40% of subjects were 30 years of age or older) may have helped motivate them to want to change their life. The active participation of probation and parole officers may have provided an additional incentive. The implications of that study (Cooper et al.) for the present re-injury prevention planning are that it may be worthwhile to consider different program approaches for different age groups. In addition, because the majority of patients interviewed in Study #2 had prior histories of criminal activity and criminal justice involvement, parole and probation officers may be part of the intervention planning team (as was done in the Cooper et al., [2006] study). As Lauritsen and colleagues (1992, p. 101) note, adolescent victims and offenders “do not constitute mutually exclusive groups.” The implication is that victimization and delinquency prevention efforts should be combined (at least for the adolescent victims). CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 89 * Limitations Project staff faced certain limitations. It is unfortunately not possible to directly compare the GSW data with police data about the shooting incidents, as it was not part of the study’s design. We attempted to address this issue by contacting local police, but were unable to obtain a copy of their electronic data file of police shooting-hits. In other words, while hospital injury surveillance data may catch some crimes missing in other criminal justice data sources, it is not possible to conduct that analysis with these data. That said, we feel that the inclusion of the socio-structural variables helps illuminate some of the neighborhood social and economic characteristics related to gun violence rates. Maps could only be created for those patients who were brought to the Trauma Center via EMS (i.e., about half of the GSW sample). The locations of the shooting for those patients brought to the Trauma Center via private car, for instance, are unknown. Despite the missing data, the spatial and day/ time analyses revealed that certain areas of the city were significantly more likely to produce GSW victims; and that more GSW victims were admitted to the Trauma Center on Sunday and Monday, as well as during the late night/ early morning hours. Data like these can help inform the resource allocation planning of local police. To that end, during the study period monthly reports were issued to a local safety planning coalition composed of police and various community agencies. In Study #1, data such as the context for the shooting remained elusive. Contextual information about the incidents was sometimes found in supplemental sources (e.g., local newspapers). Notations by medical staff regarding the circumstances tended to be short and non-illustrative (e.g., “patient heard one shot;” “patient recalls events of the assault,” with no further details provided). Details about the victim-perpetrator relationship were typically not recorded in the patient medical charts. This realization provided the impetus for undertaking Study #2, to be able to obtain these contextual factors. Because Study #2 involved direct questioning of patients, more detail was obtained about the circumstances related to the attack. Some patients were reluctant to disclose full details about their assault (similar to criticisms, discussed earlier, of victimization self-report data). One subject, for instance, said he was approaching a bus stop and noticed some kids fighting. He noted that “someone punched me and I was stabbed by a stranger,” suggesting he was neither involved nor knowledgeable about why this happened. Fortunately, other patients were more forthcoming: one subject said he was shot by the boyfriend of a young woman he had flirted with (after he beat up the boyfriend, who subsequently left and returned with a gun). Another subject thought he might have been stabbed because his friends are either gang members or gang-friendly (although he claimed not to be a gang member himself). 90 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY * Conclusion Hospital surveillance data on assault injury have not been in the forefront of many criminologists’ thoughts. Perhaps that should change, however. This article presents the results from, and prevention implications of, two studies using hospital data on intentional assault injury. Hospital data on serious assault such as being shot offer undeniable evidence of a crime, thereby addressing some of the validity problems of self-report victimization data, for instance. While some of the findings from the present studies support what is already known from other criminal justice research (e.g., repeat victimization), the visual presentation of the geographic locations of the shootings is a new contribution for studies using hospital data. The studies highlight the intersection of the medical/public health and criminal justice fields. Assault-injured patients, as well as their families, are vulnerable individuals in great need of assistance. The hospitals that treat them represent a catchment point through which the victims can be reached. The authors would encourage criminologists to venture into nontraditional settings to plan prevention and intervention programs, as well as to conduct their research. In a similar vein, medical staff can think of themselves as part of the criminal justice community. CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 91 * References Becker, M.G., Hall, J. S., Ursic, C. M., Jain, S., & Calhoun, D. (2004). Caught in the Crossfire: The effects of a peer-based intervention program for violently injured youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 177–183. Boggess, S., & Bound, J. (1997). Did criminal activity increase during the 1980’s? Comparisons across data sources. Social Science Quarterly, 78(3), 725–739. Boyle, D. J., & Hassett-Walker, C. (in press). Individual-level and socio-structural characteristics of violence: An emergency department study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Broidy, L., & Agnew, R. (1997). Gender and crime: A general strain theory perspective. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 34(3), 275–306. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Criminal victimization in the United States: 2005 Statistical Tables (NCJ 215244). Washington, DC: Author. Bursik, R. J. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and prospects. Criminology, 26, 519–551. Cohen, J., & Lynch, J. P. (2007). Exploring differences in estimates of visits to emergency rooms for injuries from assaults using the NCVS and NHAMCS. In J. P. Lynch & L.A. Addington (Eds.), Understanding crime statistics: Revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and UCR (pp.183–222). New York: Cambridge University Press. Cook, P. J. (1985). The case of the missing victims: Gunshot woundings in the National Crime Survey. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1(1), 91–102. Cooper, C., Eslinger, D. M., & Stolley, P. D. (2006). Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 61(3), 534–540. Decker, S. H., Curry, G. D., Catalano, S., Watkins, A., & Green, L. (2005). Strategic Approaches to Community Safety Initiative (SACSI) in St. Louis. Final Report to the National Institute of Justice (Award No. 2000-IJ-CXK008). Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. Eck, J. E., Chainey, S., Cameron, J. G., Leitner, M., & Wilson, R. E. (2005). Mapping crime: Understanding hotspots. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. Ellingworth, D., Hope, T., Osborn, D. R., Trickett, A., & Pease, K. (1997). Prior victimization and crime risk. International Journal of Risk, Security, and Crime Prevention, 2(3), 201–215. Fagan, J., & Wilkinson, D. L. (1998). Guns, youth violence, and social identity in inner cities. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research: Vol. 24 (pp.105–188). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. In N. Morris and M. Tonry (Eds.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research: Vol. 7 (pp.189–250). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 92 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2001). Crime in the United States, 2000. Washington, DC: Author. Frazier, C. E., Bock, E. W., & Henretta, J. C. (1983). The role of probation officers in determining gender differences in sentencing severity. Sociological Quarterly, 24, 305–318. Gotsch, K. E., Annest, J. L., Mercy, J. A., & Ryan, G. W. (2001). Surveillance for fatal and nonfatal firearms-related injuries – United States, 1993–1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 50 (SS-02), 1–32. Gove, W. R., Hughes, M., & Geerken, M. (1985). Are Uniform Crime Reports a valid indicator of the index crimes? An affirmative answer with minor qualifications. Criminology, 23(3), 451–501. Graitcer, P. L. (1987). The development of state and local injury surveillance systems. Journal of Safety Research, 18, 191–198. Harrison, P. M., & Beck, A. J. (2002). Prisoners in 2001. (Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin NCJ195189). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Hausman, A. J., Prothrow-Stith, D., & Spivak, H. (1995). Implementation of violence prevention education in clinical settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 25, 205–210. Hawkins, D. F., Laub, J. H., & Lauritsen, J. L. (1998). Race, ethnicity, and serious juvenile offending. In R. L. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders (pp.30–46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1989). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89(3), 552–584. Hutson, H. R., Anglin, D., & Pratts, M. J. (1994). Adolescents and children injured or killed in drive-by shootings in Los Angeles. New England Journal of Medicine, 330(5), 324–327. Jenson, G. F., & Brownfield, D. (1986). Gender, lifestyles, and victimization: Beyond routine activity. Violence and Victims, 1(2), 85–99. Jenson, J. M., & Howard, M. O. (1999). Prevalence and patterns of youth violence. In J. M. Jenson & M. O. Howard (Eds.), Youth violence: Current research and recent practice innovations (pp. 3–18). Washington, DC: NASW Press. LaFree, G. (1995). Race and crime trends in the United States, 1946–1990. In D. Hawkins (Ed.), Ethnicity, race, and crime (pp. 169–193). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. LaFree, G. (1998). Losing legitimacy: Street crime and the decline of social institutions in America. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Land, K., McCall, P., & Cohen, L. E. (1990). Structural covariates of homicide rates: Are there any invariances across time and space? American Journal of Sociology, 95, 922–963. Lauritsen, J. L., & Davis Quinet, K. F. (1995). Repeat victimization among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 11(2), 143–166. CONDUCTING CRIMINOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN A HOSPITAL • 93 Lauritsen, J. L., Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (1992). Conventional and delinquent activities: Implications for the prevention of violent victimization among adolescents. Violence and Victims, (7)2, 91–108. Lavery, R. F., White, T., Mosenthal, A. C., Hauser, C. J., Livingston, D. H., & Ross, S. E. (1999). The decline of violence at an urban, Level I Trauma Center. Journal of Trauma, 46(1), 206. Litaker, D. (1996). Preventing recurring injuries from violence: The risk of assault among Cleveland youth after hospitalization. American Journal of Public Health, 86(11), 1633–1636. Marciniak, E. M. (1994). Community policing of domestic violence: Neighborhood differences in the effect of arrest. Dissertation. College Park, MD: University of Maryland. Maxfield, M. G. (1999). The National Incident-Based Reporting System: Research and policy implications. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 15(2), 119–149. McBride, C. M., Emmons, K. M., & Lipkus, I. M. (2003). Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Education Research, 18(2), 156–170. Mitka, M. (1998). “Teachable moments” provide a means for physicians to lower alcohol abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association, 22(279), 1767–1768. Moscovitz, H., Degutis, L., Bruno, G. R., & Schriver, J. (1997). Emergency department patients with assault injuries: Previous injury and assault convictions. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 29(6), 770–775. National Research Council. (2001). Juvenile crime, juvenile justice. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. O’Brien, R. M. (1996). Police productivity and crime rates: 1973–1992. Criminology, 34(2), 183–207. Parker, R. N. (1989). Poverty, subculture of violence, and type of homicide. Social Forces, 67(4), 983–1007. Rand, M. R. (1997). Violence-related injuries treated in hospital emergency departments. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (pp. 1–11, NCJ 156921). Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Rapp-Paglicci, L. A., & Wodarski, J. S. (2000). Antecedent behaviors of male youth victimization: An exploratory study. Deviant Behavior, 21, 519–536. Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology 94, 774–802. Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 443–478. Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924. 94 • JUSTICE RESEARCH AND POLICY Sampson, R. J., & Wilson, W. J. (1995). Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality. In J. Hagan & R. D. Peterson (Eds.), Crime and inequality (pp. 37–54). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Sege, R., Stringham, P., Short, S., & Griffith, H. (1999). Ten years after: Examination of adolescent screening questions that predict future violence-related injury. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24, 395–402. Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency in urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Singer, S. I. (1981). Homogeneous victim-offender populations: A review and some research implications. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 72(2), 779–788. Singleton, R. A., & Straits, B. C. (2005). Approaches to social research. New York: Oxford University Press. State of New Jersey, Division of State Police (2006). Crime in New Jersey: 2005 Uniform Crime Report. West Trenton, NJ: Author. Steffensmeier, D. J., Allan, E. A., Harer, M. D., & Streifel, C. (1989). Age and the distribution of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 803–831. Stevens, V. J., Severson, H., Lichtenstein, E., Little, S. J., & Leben, J. (1995). Making the most of a teachable moment: A smokeless-tobacco cessation intervention in the dental office. American Journal of Public Health, 85(2), 231–235. Strom, K. J. (2000). Using hospital emergency room data to assess intimate violence-related injuries. Justice Research and Policy, 2(1), 1–20. Tseloni, A., & Pease, K. (2004). Random effects, event dependence, and unexplained heterogeneity. British Journal of Criminology, 44(6), 931–945. U.S. Census. (2000). Profile of general demographic characteristics. Data set: Census 2000 summary file 1 (SF1) 100-percent data. Walklate, S. (2001). Gender, crime, and criminal justice. Cullompton, Devon, UK: Willan Publishing. Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Wilt, S. A., & Gabrel, C. S. (1998). Weapon-related injury surveillance system in New York City. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Supplement, 3, 75–82. Zun, L. S., Downey, L. V., & Rosen, J. (2006). The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24, 8–13.