Sample Chapter - Carswell Desk Copy

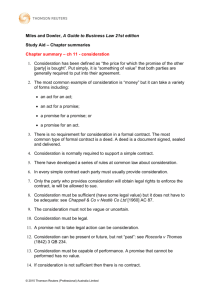

advertisement