Series two, article four: Different types of evidence/literature reviews

advertisement

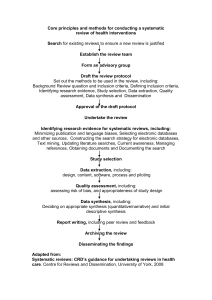

Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review Article Four – Different Types of Evidence / Literature Reviews The rapid growth in the number of reviews undertaken can partly be explained by the current emphasis on evidence-based practice. Healthcare practitioners such as pharmacists need accurate, up-to-date information about what works and they often look to evidence reviews for this. In addition, changes in information technology means that a vast amount of evidence is increasingly accessible to a wider audience. This often needs to be collated and represented in order to be used by practitioners, policy-makers and commissioners. This article outlines the key features of different types of review and discusses their similarities and differences. However, it is important to remember that the terms used to describe review approaches are not always well defined or used consistently. This article will help you to identify just what type of review you are reading and to understand its potential uses and limitations. Systematic reviews are the most scientifically robust reviews and, as such, are regarded as the ‘gold standard’. However, it is not always appropriate to undertake a systematic review. For example, there may be insufficient numbers of primary studies (original research) available or the methodological nature of the studies may make them unsuitable for systematic review. In this sense, there is no single ‘ideal type’ of review. In the same way that the research method you employ is dependent upon your research question1; the type of review undertaken will also be determined by the question or topic it seeks to address. Systematic Reviews Systematic reviews are reviews in which the evidence from a number of studies is gathered together in one report. The review pools and analyses all available data to assess the overall strength of the evidence2. Systematic methods are used to identify original research which is relevant to the review question. These primary studies are then evaluated to ensure they are methodologically and analytically robust. Studies that do not meet stringent quality criteria are excluded from the review. Reviewing only high quality studies that are relevant to your review question ensures that bias is minimised and reliable results are produced. One example of a systematic review is that conducted by Watson et al ‘Oral versus intra-vaginal imidazole and triazole anti-fungal agents for the treatment of uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush): a systematic review’. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01142.x/pdf 1 Pharmacy Research & Evaluation Resources, series one, article one http://www.rpharms.com/seriesone--planning-research/article-one.asp 2 Sense about Science, 2009, ‘Systematic Reviews’ http://www.senseaboutscience.org.uk/PDF/SenseAboutSystematicReviews.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 1 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review By definition, this was a review of previous studies which compared oral versus intra-vaginal anti-fungal treatments. The review team devised clear and explicit inclusion, exclusion, methodological and quality criteria which ensured that the studies included were appropriate. During the search stage of the review, 833 potential publications were identified. Of these, 811 were excluded as not relevant to the purpose of the review. Of the remaining 22 comparative trials, a further 5 were excluded on methodological or clinical grounds (i.e. random allocation was not specified or the participants had recurrent rather than acute candidiasis). Although it may seem counterintuitive to eliminate apparently relevant studies, it is essential to evaluate a study’s methodological quality before inclusion. If studies with poor methodology are included then their results might distort the review’s conclusion. Ensuring that included studies are robust is more important than simply getting more data3. The key components of a systematic review are: A clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies An explicit, reproducible methodology A systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria An assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of risk of bias A systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies Because of their importance in delivering evidence-based practice, systematic reviews should be an integral part of a pharmacist’s professional life. To coincide with the release of this series, Dr Margaret Watson, a pharmacist with an impressive track record of published systematic reviews, presented a webinar which provides additional information and guidance on understanding and undertaking systematic reviews. The webinar discussed: The rationale for conducting systematic reviews The difference between systematic and non-systematic reviews The key components of systematic reviews The quality markers of systematic reviews The relevance of systematic reviews to pharmacy practice Access to the webinar can be found here https://rpsgb.webex.com/rpsgb/lsr.php?AT=pb&SP=EC&rID=10388242&rKey =0D74481C3C1D12D5 Meta-analysis 3 Sense about Science, 2009, ‘Systematic Reviews’ Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 2 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review Meta-analysis refers to the use of statistical techniques to integrate the results of primary studies. Combining the results of several studies can give a more reliable and precise estimate of an intervention’s effectiveness than one study alone. A meta-analysis provides increased numbers of participants, reduces random error, narrows confidence intervals, and provides a greater chance of detecting a real effect as statistically significant (i.e. increases statistical power)4. Many systematic reviews limit their inclusion criteria to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with comparable designs, particularly if they are reviewing the evidence on the efficacy of a particular medicine. Because of this, metaanalysis is possible and desirable in some (thought not all) systematic reviews. However, not all systematic reviews limit their inclusion criteria to RCTs, either because insufficient numbers of RCTs have been conducted, or because the review question would not be appropriately addresses through the conduct of RCTs, or the analysis of existing RCT data. This means that meta-analysis is not always possible or sensible – in order to conduct a meta-analysis you need to be able to compare like with like. Meta-analysis of methodologically diverse or poor quality studies could be seriously misleading as errors or biases in individual studies would be compounded and the very act of synthesis may give credence to poor quality studies. When used appropriately meta-analysis has the advantage of being explicit in the way that data from individual studies are combined. It is a powerful tool in helping avoid misinterpretation and allowing meaningful conclusions to be drawn across studies5. Narrative synthesis Narrative synthesis refers to the adoption of a textual (as opposed to statistical) approach that provides an analysis of the relationships within and between studies and an overall assessment of the robustness of the evidence. A narrative synthesis of studies may be undertaken where studies are too diverse (either clinically or methodologically) to combine in a meta-analysis. Even where a meta-analysis is possible, aspects of narrative synthesis will usually be required in order to fully interpret the collected evidence. Because narrative synthesis is inherently a more subjective process than meta-analysis, it is crucial that the approach used to analyse and assess the evidence is rigorous and transparent. This will reduce the potential for bias and ensure the review is replicable. 4 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009, ‘Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care’, http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf 5 As above Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 3 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review Narrative review normally consists of the following four elements, each of which needs to be adequately explained with the review. • Developing a theory of how the intervention works, why and for whom • Developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies • Exploring relationships within and between studies • Assessing the robustness of the synthesis The idea of narrative synthesis within a systematic review should not be confused with broader terms like ‘narrative review’, which are sometimes used to describe reviews that are not systematic6. Realist Reviews Some healthcare interventions, such as administering a specific drug for the treatment of an acute condition, are conceptually simple and their effectiveness will generally have been evaluated in RCTs. Evaluating and comparing interventions such as these are most appropriately addressed through a systematic review. Many healthcare interventions though, are more complex and their effectiveness is dependent upon the context in which they are applied. Economic, environmental, social and individual factors can all play a part in determining whether or not an intervention will succeed. Alternative forms of review need to be undertaken in order to examine the relationship between the intervention and context which is so often central to an intervention’s efficacy. Indeed, the systematic review of oral versus intra-vaginal anti-fungal treatment for thrush alludes to this social context by attempting to establish patient preferred route of administration. Because there was limited data which addressed this secondary outcome of the review, the authors were unable to definitively state patient preferred route. However, as pharmacists you will be acutely aware of the need to provide treatments with which patients will adhere. A drug that has been proved to be more effective than another through RCTs will not necessarily be more effective if it is not taken as prescribed in the ‘real world’ of the patient. Realist reviews are concerned with the identification of underlying causal mechanisms, how they work, and under what conditions. Fundamentally, they focus attention on finding out what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances7. To achieve this, realist reviews typically draw on a wide range of studies that use diverse research methods (both quantitative and qualitative). 6 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009, ‘Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care’, http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf 7 Rycroft-Malone, J. et al 2010, ‘A realistic evaluation: the case of protocol-based care’, Implementation Science 2010,58 Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 4 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review In contrast to systematic reviews, realist reviews do not begin with a clearly defined protocol setting out the criteria under which studies will be excluded. This does not mean however, that the review will begin without a search strategy. Reviewers should have given much thought to the key words they will search for and the databases they will use. Unlike a systematic review though, the search process will be more iterative and will be refined and developed as the review progresses. The search is likely to begin with a background search to get a feel for the literature – what is there, what form it takes, where it seems to be located and how much there is. This will then be followed by a search for empirical evidence from a range of primary studies using a variety of research strategies. At this stage, the reviewer should provide a formal audit trail. In realist reviews, studies are not quality assessed in the same way as when undertaking systematic reviews. During synthesis, the relative contribution of each source is assessed and the reasoning behind decisions reached is made explicit. For example, the analysis spells out the grounds for being cautious about A because of what we have learned from B and what was indicated in C. The worth of studies is established in synthesis and not as a preliminary prequalification exercise. Unlike systematic reviews, realist reviews are not standardized or replicable8. The key components of a realist review are: A focus on context and process They draw on a range of methodologically diverse material The protocol is iterative rather than pre-defined The value of studies is established in synthesis They are not standardized or replicable Reviews which combine quantitative and qualitative studies In addition to realist reviews, other review methods enable the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative empirical studies. This is usually done to enhance the relevance of the review in the decision making process by including some aspect of social context. One example of this is Raynor et al’s (2007) “A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative research on the role and effectiveness of written information available to patients about individual medicines.” http://www.hta.ac.uk/fullmono/mon1105.pdf 8 Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005), ‘Realist Review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions’, http://pram.mcgill.ca/seminars/i/Pawson-2005-Realist-Review-Essay.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 5 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review The aim of this review was: ‘To establish the role and value of written information available to patients about individual medicines from the perspective of patients, carers and professionals and, ‘ To determine how effective this information is in improving patients’ knowledge and understanding of treatment and health outcomes’. In order to undertake this review, databases was searched for research on (a) the role and value and (b) the effectiveness of written patient information for individual medicines. The role and value studies were defined as those examining the use and usefulness of written medicines information. Effectiveness trials were defined as RCTs which examined how well written medicines information works. From over 50,000 ‘hits’, 413 studies were considered. Of these, 64 papers reporting 70 studies were included: 36 papers reporting 43 RCTs in the effectiveness strand and 28 in the role and value strand. Qualitative Reviews There are many methods available for synthesising qualitative data in order to produce a review on a particular research question or topic. In order to understand or undertake qualitative reviews it is essential that you have a good understanding of qualitative research methods and methods of analysis (both of which will be covered in future series of these Pharmacy Practice Research & Evaluation Resources). In essence, qualitative reviews or qualitative synthesis “is sometimes defined as a process resulting in a 'whole' which is more than the sum of its parts. However, the methods vary in the extent to which they attempt to 'go beyond' the primary studies and transform the data. Some methods – textual narrative synthesis, ecological triangulation and framework synthesis – focus on describing and summarising their primary data (often in a highly structured and detailed way) and translating the studies into one another. Others – metaethnography, grounded theory, thematic synthesis, meta-study, metanarrative and critical interpretive synthesis – seek to push beyond the original data to a fresh interpretation of the phenomena under review”9. Scoping reviews Scoping reviews aim to map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available. Scoping reviews provide wide coverage of the available literature but can vary enormously in the degree to which they extract, analyse and re-present the available evidence. The extent to which the review provides an analysis of evidence 9 Barnett-Page, E & Thomas, J. (2009), ‘Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review’, http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2288-9-59.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 6 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review depends on the purpose of the review and Arksey & O’Malley have identified four common reasons why a scoping review might be undertaken10: 1. To examine the extent, range and nature of research activity This type of rapid review might not describe research findings in any detail but is a useful way of mapping fields of study where it is difficult to visualise the range of material in existence. 2. To determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review In these cases a preliminary mapping of the literature might be undertaken to identify whether or not a full systematic review is feasible (does any literature exist?) or relevant (have systematic reviews already been conducted?) and the potential costs of conducting a full systematic review. 3. To summarise and disseminate research findings This kind of scoping study might describe in more detail the findings and range of research in particular areas of study, thereby providing a mechanism for summarising and disseminating research findings to practitioners, policy makers and consumers who might otherwise lack the time or resources to undertake such work themselves (Antman et al. 1992). 4. To identify research gaps in the existing literature This type of scoping study takes the process of dissemination one step further by drawing conclusions from existing literature regarding the overall state of research activity. Specifically designed to identify gaps in the evidence base where no research has been conducted, the study may also summarise and disseminate research findings as well as identify the relevance of a full systematic review in specific areas of interest. As with any review, the first stage is to devise a well thought-out search strategy which includes key terms to be used and databases to be searched. In contrast to systematic reviews, the final parameters of the search need not be finalised prior to beginning the review. Like realist reviews it is often more relevant “to maintain a wide approach in order to generate breadth of coverage. Decisions about how to set parameters can be made once some sense of the volume and general scope of the field has been gained.”11 As has been mentioned throughout these resources, using existing knowledge and networks can prove extremely fruitful and this is equally true in generating information about primary research. Likewise, contacting relevant national or local organisations working in the field is useful in identifying unpublished work. In their example of conducting a scoping review whose research question was: What is known from the existing literature about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of services to support carers of people 10 Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005), ‘Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework’, http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1618/1/Scopingstudies.pdf 11 Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005), ‘Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework’, http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1618/1/Scopingstudies.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 7 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review with mental health problems?, the reviewers contacted a number of relevant organisations including Carers UK, the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, the Mental Health Foundation, the King’s Fund, and the National Schizophrenia Fellowship12. Once a review is underway, familiarity with the available literature will enable the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine which potential articles are actually relevant to addressing the review question. As with other types of review, data from primary sources then needs to be extracted and organised in some way in order to undertake analysis and / or present the review’s findings. How data is organised and / or analysed will be dependant on the purpose of the scoping review and the types of evidence retrieved. For example, you might simply be providing a map of the existing literature in order to determine what is out there and whether there are gaps in the evidence base. If your aim is to summarise findings, techniques more commonly used to interpret qualitative data might be used. This usually involves ‘sifting, charting and sorting material according to key issues and themes13. Identified themes can include information about the processes involved in the intervention or the context in which the intervention was used. Although useful in many respects, scoping reviews do have their limitations and these need to be borne in mind. The quantity of data generated during a scoping review can be considerable. This can lead to difficult decisions regarding the compromise between breadth (covering all available material) and depth (providing a detailed analysis and appraisal of a smaller number of studies). In addition, scoping reviews do not quality assess primary studies in any formal sense and consequently, they provide a narrative or descriptive account of available research”14. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping studies are not appropriate to answer a clinical question. The key components of a scoping review are: to map key concepts to map main sources and types of evidence to identify gaps in the evidence base to determine the value of undertaking a systematic review focus on providing wide coverage need to compromise between breadth and depth Rapid Evidence Reviews 12 As above 13 Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005), ‘Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework’, http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1618/1/Scopingstudies.pdf 14 As above Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 8 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review “Rapid evidence reviews are used to summarise the available research evidence within the constraints of a given timetable, typically three months or less. Rapid evidence assessments differ from full systematic reviews in terms of time constraints. Consequently there are limitations on the extent of the searches and other review activities. Whilst attempting to be as comprehensive as possible, rapid evidence assessments usually make compromises to meet their tight deadlines; therefore they may fail to identify potentially relevant studies. They are useful to policy-makers who need to make decisions quickly, but should be viewed as provisional appraisals, rather than full systematic reviews”15. Conclusion Different reviews employ different methods and these are dependent upon the question which the review seeks to address. In order to assess the strengths and weaknesses of any review, it is essential to have a good understanding of both review methods and research methods. This will enable you determine whether or not the ones used were appropriate and what the limitations of the review are. It is important never to accept the findings of either primary or secondary research at face value. For example, not everything that is called a systematic review has used the necessary methods that would enable it to be so titled. The findings of the evidence are therefore unlikely to be as robust as those which would result form a properly conducted systematic review. Review authors should clearly state how their review was undertaken so that you can judge its value and determine whether or not it is applicable to the context in which you want to apply its findings. In addition, all reviews should provide sufficient information about the primary sources included to enable you to determine what type of evidence they were reviewing and what kinds of inferences can be made form these sources. Reviews are a valuable source of information for busy healthcare professionals but it is essential that they are subjected to the same critical appraisal as primary research. Useful Links Notting Systematic Review Course http://www.cochrane.org/events/workshops/uk-ireland-region/systematicreview-course-nottingham-uk National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools Introduction to evidence-informed decision making – online training http://www.nccmt.ca/en/modules/eidm/ 15 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009, ‘Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care’, http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 9 of 10 Pharmacy Research and Evaluation Resource Series Two: Conducting an Evidence/Literature Review Further Reading Trisha Greenhalgh, ‘How to Read a paper’ 1997 BMJ http://www.bmj.com/content/315/7109/672.full Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005), ‘Realist Review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions’, http://pram.mcgill.ca/seminars/i/Pawson-2005-Realist-ReviewEssay.pdf Royal Pharmaceutical Society © 2011 Page 10 of 10