Advanced Music Students' Use of Imagery and Metaphor

ADVANCED MUSIC STUDENTS’ USE OF

IMAGERY AND METAPHOR-BASED INSTRUCTION IN

GENERATING EXPRESSIVE PERFORMANCE

Robert H. Woody

School of Music, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588-0100 USA rwoody2@unl.edu

ABSTRACT

This study addressed the cognitive processes of musicians when using mental imagery to improve their expressive performance of a melody. Specifically it examined the extent to which musicians use a strategy of translating the imagery into an explicit plan of how to perform certain sound properties of the music. Subjects were 70 undergraduate and graduate music majors at a university. They were provided with a research packet to be completed in an individual practice session on their own time. Subjects worked with three melodies, each accompanied by an imagery example that was presented as a music teacher’s instructions for making a performance of the melody more expressive. The pages of the research packet guided subjects in considering the imagery-based instruction, practicing in light of it, and giving a final performance, all the while writing down their thought processes during the procedure. Results indicated that some of the musicians did use a cognitive translation process, but others employed a more emotion-based strategy with which the provided imagery is developed and personalized. Most interestingly, subjects who had received more cumulated private instruction tended to utilize a cognitive translation process when working with the imagery examples.

1.

INTRODUCTION

When working with young musicians whose performance is lacking expressively, many music teachers attempt to remedy the problem by using mental imagery. They might verbally describe for their students an emotional situation or an image of an object that possesses some quality to be duplicated in the music. It is assumed that when performing musicians, for example, feel the excitement of being in love or imagine the graceful movement of a soaring eagle, their performances are more expressive. Research has confirmed that the use of mental imagery and metaphors is well endorsed by the music teaching profession (Barten, 1992; Davidson, 1989; Tait,

1992; Woody, 2000).

There appear to be multiple reasons why music teachers use mental imagery with their students. Barten (1998) identified the effectiveness of metaphorical verbal instruction for teaching the physical skills of music performance. For example, rather than giving a beginning flutist anatomically based information about an open mouth cavity, a music teacher might simply have the student imagining a hot potato in the mouth. Instructors also use imagery of movement, such as an object traveling through the air and falling to the ground, to bring attention to the motional aspects of music, perhaps invoking musical concepts of “phrase” and “line” (Barten,

1992). Finally, imagery and metaphorical language is largely used by music educators to address the emotionally expressive dimension of music performance. It is a commonly held belief that a prerequisite to truly expressive performance is strong felt emotion or an “affective state” within the performer (Davidson, 1989). One college musician quoted in a study by Woody (2000) characterized a performer’s unemotional use of dynamics and tempo as

“simulating expressivity” (p. 18).

When choosing an image or metaphor example to share with students, music teachers likely first draw upon the compositional structure of the music being performed (Woody, 2002). That is, the type of imagery that would be appropriate for a given piece is limited by its tonality (major or minor), rhythmic framework, and melodic structure (among other things). Perhaps this is why music teachers’ use of imagery is often accompanied by their providing an aural model of a piece. In such cases, listening students may use the image as an “extramusical template” for committing to memory the sound of the modeled performance (Sloboda, 1996). Of course some teachers do not provide models and are more eccentric with their uses of imagery. Persson (1996) documented some potential hazards of this approach in a case study of an acclaimed concert pianist who outlined her teaching strategy as “pictures and images”

(p. 28). The teacher herself acknowledged that her intense metaphorical language left many students confused.

Greater insight is needed into the cognitive aspects of imagery-based music teaching. In other words, what happens within the minds of student musicians after being provided with a mental image by their teacher? It would seem that there are two broad strategies that students might use. First, they might exclusively focus their mental energies on “mustering up” certain felt emotions evoked by the imagery. With this approach, students must trust that their emotional state will somehow affect the sound properties of their performance. This strategy is a commonly used one, based on the results of Woody (2000), who reported that college music majors devoted the largest proportion of their practice time to

“working on felt emotion.” An alternative cognitive strategy is a translation process by which the imagery is used to build an explicit plan of how to perform certain sound properties of the music.

Woody’s (2001) results suggested that advanced music students, when given an example of imagery or metaphor, are most able to change their expressive performance when they generate concrete plans for implementing variations in articulation, dynamics, and tempo. The purpose of the present study was to provide insight into

ISBN 1-876346-50-7 © 2004 ICMPC 482

ICMPC8, Evanston, IL, USA August 3-7, 2004 the cognitive processes of musicians when using mental imagery to improve their expressive performance of a melody.

2.

METHOD

2.1

Subjects

Subjects were 70 undergraduate and graduate music majors at the researcher’s university. Subject ages ranged from 18 to 44 with a mean age of 21.3. The sample consisted of 38 females and 32 males.

2.2

Materials

The musical materials used in the study consisted of the three short melodies shown in Figure 1. All three melodies have been used in previous studies of expressive music performance (Woody, 2002).

Melody 1 was written for use in an experiment by Clarke and

Baker-Short (1987). Melodies 2 and 3 are from the Schubert song cycles Die Winterreise and Die schöne Müllerin, respectively, and were both used in research by Clarke (1993) and Woody (1999).

Figure 1: The three melodies used in the study.

In the print materials supplied to subjects, each melody was accompanied by imagery-based text that served as instructions for making the performance of the melody expressive. The specific imagery examples were drawn from Woody (2002). In that study, college professors of applied music performance contributed examples of descriptive imagery that they would use with students.

The resulting pool of examples was evaluated by a panel of expert music educators to determine the single best (highest rated) imagery example for each melody (greater detail about this process can be found in Woody, 2002). The three imagery examples were:

Melody 1:

Play with sadness and intensity as you would when expressing the loss of a loved one.

There’s the bittersweet remembrance of great tenderness and great loss.

Melody 2: The character suggests one who is pensive, reflective, searching, exploring.

Melody 3: Bouncy and happy. Rustic, as if you’re a happy peasant, with no cares or worries, strolling along, singing a song.

2.3

Procedure

A research packet was designed so musicians could carry out the procedure in an individual practice session on their own time.

Participating students chose from packets with the melodies notated in treble, bass, or alto clef. After a page of general instructions, the next three pages contained one of the melodies and an imagery example, presented as a music teacher’s instructions for making a performance of the melody more expressive.

Each page consisted of step-by-step instructions for considering the imagery, practicing the melody in light of it, and giving a final performance. Throughout this, subjects were questioned about their thought processes and wrote their responses on the page. Each page also had subjects indicate how many times they practiced the melody, rate how effective the imagery-based instructions were in making their performance more expressive (on a 5-point Likert scale), and explain why they felt that way. All subjects completed a page for each of the three melodies, but the presentation order of the three was counterbalanced across the sample.

The packet’s final page collected musical demographic data, including principal instrument and number of years receiving private instruction.

2.4

Data Analysis

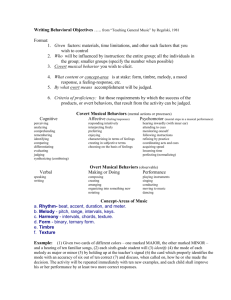

Subjects’ written responses in the research packets were transcribed into computer text files. Subjects’ responses to questions about their thinking were then analyzed in terms of the extent that their thought processes reflected translating the provided imagery example into plans for concrete musical properties. This analysis considered five concrete musical elements that are used to make music performances sound expressive, namely articulation, dynamics, tempo, timbre, and pitch vibrato. A four-level scoring rubric was applied to each subject’s responses for each melody to indicate the extent to which a cognitive translation process was used. Each was assigned one of the numerical codes described in Table 1. Using this system, a “cognitive translation” index was computed by adding up each subjects scores for all three melodies.

Rating Description

0 All thoughts are emotion or imagery-based, no musical elements addressed

1 Thoughts are mostly emotion or imagery-based, 1 or 2 musical elements are addressed nonspecifically

2 Little thought devoted to emotion or imagery, at least 2 musical elements addressed with 1 addressed in terms of specific locations in the melody

3

Very little or no thought devoted to emotion or imagery, at least 3 musical elements addressed with 2 (or more) addressed in terms of specific locations in the melody

Table 1: Scoring rubric for coding subject responses about their thought processes while working with the imagery examples.

3.

RESULTS

Results showed that subjects dealt with all three melodies similarly.

The averages for number of times subjects practiced each melody were: Melody 1 M = 3.92, Melody 2 M = 4.54, and Melody 3 M =

3.90. Subjects also indicated for each melody how effective they

483

ICMPC8, Evanston, IL, USA August 3-7, 2004 thought the provided imagery example was in making their performance more expressive, using a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all effective, 5 = very effective). The average ratings for the melodies were: Melody 1 M = 4.00, Melody 2 M = 3.12, and

Melody 3 M = 3.91. These ratings suggest that subjects generally believed the imagery-based instructions to be useful in guiding their expressive performance attempts. Interestingly, the lowest rated imagery example of Melody 2 corresponded with the melody that was practiced the most. Subject written comments suggested that many of them did not know what the word “pensive” means or did not understand how to interpret it musically—and others expressed concern about technically executing the ascending 7th interval in their performance.

The average cognitive translation scores, using the 0 to 3 rubric, were as follows: Melody 1 M = 1.20, Melody 2 M = 1.11, and

Melody 3

M

= 1.27. There were no statistically significant differences between these scores. In fact, the correlation matrix in

Table 2 shows positive relationships among the scores for the sample. This indicates that subjects tended to use the same type of strategy (with regard to cognitive translation or focus on felt emotion) with all melodies.

Melody 1

Melody 1

1.000

Also conducted was a qualitative analysis of subjects’ transcribed comments about their thought processes while practicing the melodies in light of the imagery-based instructions. These subject responses illustrated interesting contrasts between strategies for using mental imagery to guide expressive performance. Consider the following example of a subject working with the imagery provided for Melody 3:

Subject #57

(thinking while preparing) Tempo, space between the notes, ‘going to’ the D in the dotted rhythm, sounding happy!

(thinking while performing) I could put a crescendo through the four Ds preceding the dotted rhythm to make it ‘go to’ the D in the dotted rhythm and make the whole line go somewhere. Putting vibrato on the longer notes.

(thinking while practicing for best performance)

Still thought of a bouncy feel, but making a line out of it. I put a crescendo through the first four eighth notes, slurred the first two sixteenth notes to give them ‘something’.

Melody 2 Melody 3

Melody 2 .560* 1.000

Melody 3 .450* .521* 1.000

* p < .01

Table 2:

Correlations between subjects’ cognitive translation scores for the three melodies.

This subject did not mentally develop the imagery at all, but devoted virtually all attention to formulating a plan for incorporating variations in dynamics and articulation in specific points of the melody. Using the translation scoring rubric, this subject’s work with this melody was scored a 3. This use of the cognitive translation approach can be contrasted to the following example, also with Melody 3:

Subject #55

(thinking while preparing) Strolling down a country road free of the chains of society, Huck

Finn. I’m reminded of walking out of the gymnasium after receiving my diploma from high school.

(thinking while performing) Light, free playing.

“Happy thoughts”.

(thinking while practicing for best performance)

Light, bouncy, happy.

This subject seems to take the imagery provided and develop it further, including individualizing it by drawing on a memory of a personal experience. Using the translation scoring rubric, this subject’s work with this melody was scored a 0.

Of course, many subjects’ scores fell between these two extremes represented above. Consider, for example, another subjects’ work with Melody 3:

Subject 14

(thinking while preparing) Light bouncy articulation. What would the melody sound like if a person with the above characteristics was singing or whistling.

(thinking while performing) Rhythmic intensity.

Let end notes last a little longer. Happy, sun, green.

(thinking while practicing for best performance)

What makes the melody happy and bouncy?

Dotted eighth D needs to have presence. I thought about being happy strolling through the park on a sunny day. Cartoon-like happiness.

This musicians seems to meditate on the provided image, but also attempts to translate it into musical properties. The concrete sound property of articulation is focused on, but is not addressed with specificity to notes or measures of the melody. This example also includes what might be called “quasi-musical” properties in the references to “intensity” and “presence.” Using the translation scoring rubric, this subject’s work with this melody was scored a 1.

The research packet’s final page questionnaire had subjects indicate the number of years they received private lessons as a child (i.e., high school and younger) and as an adult (i.e., after high school).

Each subject’s numerical responses were added together to determine their cumulated years of private instruction received.

Using a Pearson correlation coefficient statistic, these were compared to the subject cognitive translation index. The result of this analysis showed that subjects who had received more private instruction tended to utilize a cognitive translation process when

484

ICMPC8, Evanston, IL, USA August 3-7, 2004 working with the imagery examples, r

= .302, p

< .05. A subsequent analysis helped rule out the possibility of this relationship being merely a function of maturity; the correlation between subjects’ age and their cognitive translation scores was r = .032.

4.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that musicians use a variety of cognitive strategies when dealing with mental imagery. While some tried to explicitly translate the qualities of the image into musical sound properties, others seemed to meditate on the provided imagery in an effort to personally internalize it. More basically, however, the musicians’ written comments about their thinking suggested that they must first feel mastery over the technical aspects of performance before they can turn their thoughts to any expressive consideration. When subjects identified technical challenges in the music, such as performing wide pitch intervals or uniform rhythms precisely, their thoughts were less oriented to the imagery provided.

This supports the well-accepted notion among music teachers and musicians that technically accurate performance (i.e., the correct pitches and rhythms) is a prerequisite to expressive performance.

The ultimate test of an imagery example’s merit is how it affects the expressive performance of a musician. Although the quality of the performance given by the subjects during their individual practice sessions was beyond the scope of this study, this research nevertheless addressed some relevant issues. From the subjects’ comments about their thinking during their practicing, it is clear that some of them strove to generate felt emotion in themselves while performing. It is a worthwhile reminder that listening audiences cannot “look inside” performers to ascertain their emotional intentions, but instead must rely entirely on the physical sound properties of the performance. When practicing, student musicians must be careful not to be so “caught up” in the emotion of their performing that they are unable to devote some attention to objectively self-monitoring the sounds they are producing.

Perhaps this study’s most important finding is related to the role of private instruction in developing expressive performance. The results suggested that subjects with more cumulated years of private lessons tended to utilize a cognitive translation process when working with the imagery examples. This corroborates the findings of previous research which has identified one-on-one private instruction as particularly critical in the development of skills related to expressive performance (Woody, 2003). It is reasonable to think that this individualized context is the primarily one in which aspiring musicians acquire the metaphorical vocabulary or imagery as applied to music.

Much additional research is needed in order to understand the cognitive aspects of imagery-based music performance learning.

This study suggested that more advanced musicians (i.e., those who had received more instruction) tend to use a cognitive translation process when working with mental imagery. What is less clear, however, is to what extent musicians can apply this cognitive process automatically (with little conscious awareness). Most skills that are learned start out as novel behaviors that require much thought, but with ample repetition reach a level of automaticity.

Bearing in mind that the melodies presented to subjects were unfamiliar to them, it is possible that more familiar musical material requires less explicit thought by advanced musicians. Perhaps the progression toward automaticity also occurs with the conversion of imagery to musical sound, and therefore provides an explanation for expert musicians who produce intensely expressive performances from felt emotion, seemingly with no conscious thought.

5.

REFERENCES

1. Barten, S. S. (1992b). The language of musical instruction.

Journal of Aesthetic Education, 26 (2), 53-61.

2. Barten, S. S. (1998). Speaking of music: The use of motor-affective metaphors in music instruction.

Journal of

Aesthetic Education, 32

(2), 89-97.

3. Clarke, E. F. (1993). Imitating and evaluating real and transformed musical performances.

Music Perception, 10

(3),

317-341.

4. Clarke, E. F., & Baker-Short, C. (1987). The imitation of perceived rubato: A preliminary study. Psy chology of Music,

15

(1), 58-75.

5. Davidson, L. (1989). Observing a yang ch’in lesson: Learning by modeling and metaphor.

Journal of Aesthetic Education,

23 (1), 85-99.

6. Persson, R. (1996). Brilliant performers as teachers: A case study of commonsense teaching in a conservatoire setting.

International Journal of Music Education, 28

, 25-36.

7. Sloboda, J. A. (1996). The acquisition of musical performance expertise: Deconstructing the “talent” account of individual differences in musical expressivity. In K. A. Ericsson (Ed.), The road to excellence: The acquisition of expert performance in the arts and sciences, sports and games (pp. 107-126). Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

8. Tait, M. (1992). Teaching strategies and styles. In R. Colwell

(Ed.),

Handbook of research on music teaching and learning

(pp. 525-534). New York: Schirmer.

9. Woody, R. H. (1999). The relationship between advanced musicians’ explicit planning and their expressive performance of dynamic variations in an aural modeling task.

Journal of

Research in Music Education, 47, 331-342.

10. Woody, R. H. (2000). Learning expressivity in music performance: An exploratory study. Research Studies in Music

Education, 14

, 14-23.

11. Woody, R. H. (2002). Emotion, imagery and metaphor in the acquisition of musical performance skill.

Music Education

Research, 4 (2), 213-224.

12. Woody, R. H. (2003). Explaining expressive performance:

Component cognitive skills in an aural modeling task. Journal of Research in Music Education, 51

(1), 51-63.

485