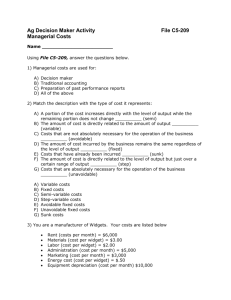

Cost Allocation and Pricing

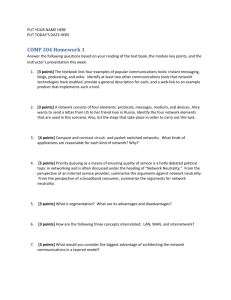

advertisement