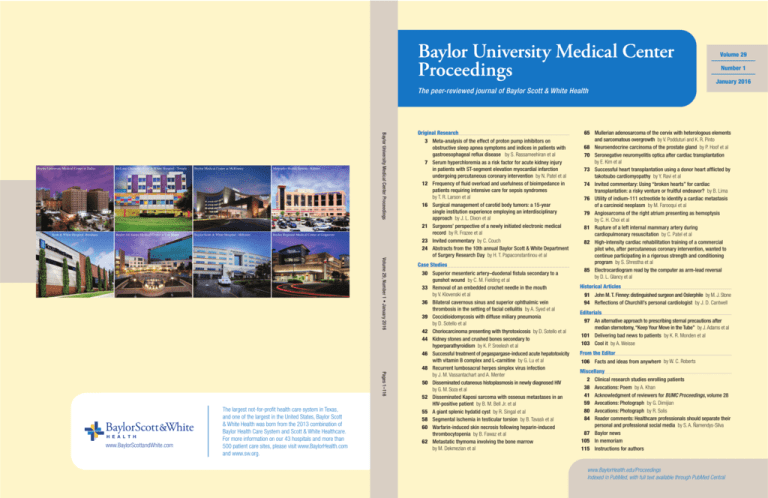

Volume 29

Number 1

January 2016

The peer-reviewed journal of Baylor Scott & White Health

Scott & White Hospital -Brenham

McLane Children’s Scott & White Hospital - Temple

Baylor Medical Center at McKinney

Metroplex Health System - Killeen

Baylor All Saints Medical Center at Fort Worth

Baylor Scott & White Hospital - Hillcrest

Baylor Regional Medical Center at Grapevine

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas

Volume 29, Number 1 • January 2016

Pages 1–116

www.BaylorScottandWhite.com

The largest not-for-profit health care system in Texas,

and one of the largest in the United States, Baylor Scott

& White Health was born from the 2013 combination of

Baylor Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare.

For more information on our 43 hospitals and more than

500 patient care sites, please visit www.BaylorHealth.com

and www.sw.org.

Original Research

3 Meta-analysis of the effect of proton pump inhibitors on

obstructive sleep apnea symptoms and indices in patients with

gastroesophageal reflux disease by S. Rassameehiran et al

7 Serum hyperchloremia as a risk factor for acute kidney injury

in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention by N. Patel et al

12 Frequency of fluid overload and usefulness of bioimpedance in

patients requiring intensive care for sepsis syndromes

by T. R. Larson et al

16 Surgical management of carotid body tumors: a 15-year

single institution experience employing an interdisciplinary

approach by J. L. Dixon et al

21 Surgeons’ perspective of a newly initiated electronic medical

record by R. Frazee et al

23 Invited commentary by C. Couch

24 Abstracts from the 10th annual Baylor Scott & White Department

of Surgery Research Day by H. T. Papaconstantinou et al

Case Studies

30 Superior mesenteric artery–duodenal fistula secondary to a

gunshot wound by C. M. Fielding et al

33 Removal of an embedded crochet needle in the mouth

by V. Klovenski et al

36 Bilateral cavernous sinus and superior ophthalmic vein

thrombosis in the setting of facial cellulitis by A. Syed et al

39 Coccidioidomycosis with diffuse miliary pneumonia

by D. Sotello et al

42 Choriocarcinoma presenting with thyrotoxicosis by D. Sotello et al

44 Kidney stones and crushed bones secondary to

hyperparathyroidism by K. P. Sreelesh et al

46 Successful treatment of pegaspargase-induced acute hepatotoxicity

with vitamin B complex and L-carnitine by G. Lu et al

48 Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex virus infection

by J. M. Vassantachart and A. Menter

50 Disseminated cutaneous histoplasmosis in newly diagnosed HIV

by G. M. Soza et al

52 Disseminated Kaposi sarcoma with osseous metastases in an

HIV-positive patient by B. M. Bell Jr. et al

55 A giant splenic hydatid cyst by R. Singal et al

58 Segmental ischemia in testicular torsion by B. Tavaslı et al

60 Warfarin-induced skin necrosis following heparin-induced

thrombocytopenia by B. Fawaz et al

62 Metastatic thymoma involving the bone marrow

by M. Dekmezian et al

65 Mullerian adenosarcoma of the cervix with heterologous elements

and sarcomatous overgrowth by V. Podduturi and K. R. Pinto

68 Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate gland by P. Hoof et al

70 Seronegative neuromyelitis optica after cardiac transplantation

by E. Kim et al

73 Successful heart transplantation using a donor heart afflicted by

takotsubo cardiomyopathy by Y. Ravi et al

74 Invited commentary: Using “broken hearts” for cardiac

transplantation: a risky venture or fruitful endeavor? by B. Lima

76 Utility of indium-111 octreotide to identify a cardiac metastasis

of a carcinoid neoplasm by M. Farooqui et al

79 Angiosarcoma of the right atrium presenting as hemoptysis

by C. H. Choi et al

81 Rupture of a left internal mammary artery during

cardiopulmonary resuscitation by C. Patel et al

82 High-intensity cardiac rehabilitation training of a commercial

pilot who, after percutaneous coronary intervention, wanted to

continue participating in a rigorous strength and conditioning

program by S. Shrestha et al

85 Electrocardiogram read by the computer as arm-lead reversal

by D. L. Glancy et al

Historical Articles

91 John M. T. Finney: distinguished surgeon and Oslerphile by M. J. Stone

94 Reflections of Churchill’s personal cardiologist by J. D. Cantwell

Editorials

97 An alternative approach to prescribing sternal precautions after

median sternotomy, “Keep Your Move in the Tube” by J. Adams et al

101 Delivering bad news to patients by K. R. Monden et al

103 Cool it by A. Weisse

From the Editor

106 Facts and ideas from anywhere by W. C. Roberts

Miscellany

Clinical research studies enrolling patients

Avocations: Poem by A. Khan

Acknowledgment of reviewers for BUMC Proceedings, volume 28

Avocations: Photograph by G. Dimijian

Avocations: Photograph by R. Solis

Reader comments: Healthcare professionals should separate their

personal and professional social media by S. A. Ñamendys-Silva

87 Baylor news

105 In memoriam

115 Instructions for authors

2

38

41

59

80

84

www.BaylorHealth.edu/Proceedings

Indexed in PubMed, with full text available through PubMed Central

Baylor University Medical Center

Proceedings

The peer-reviewed journal of Baylor Scott & White Health

Volume 29, Number 1 • January 2016

Editor in Chief

William C. Roberts, MD

Associate Editor

Michael A. E. Ramsay, MD

Founding Editor

George J. Race, MD, PhD

Steven M. Frost, MD

Dennis R. Gable, MD

D. Luke Glancy, MD

Paul A. Grayburn, MD

Bradley R. Grimsley, MD

Joseph M. Guileyardo, MD

Carson Harrod, PhD

H. A. Tillmann Hein, MD

Daragh Heitzman, MD

Priscilla A. Hollander, MD, PhD

Roger S. Khetan, MD

Göran B. Klintmalm, MD, PhD

Sally M. Knox, MD

John R. Krause, MD

Bradley T. Lembcke, MD

Jay D. Mabrey, MD

Michael J. Mack, MD

David P. Mason, MD

Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH

Gavin M. Melmed, JD, MBA, MD

Robert G. Mennel, MD

Michael Opatowsky, MD

Joyce A. O’Shaughnessy, MD

Dighton C. Packard, MD

Harry T. Papaconstantinou, MD

Gregory J. Pearl, MD

Robert P. Perrillo, MD

Daniel E. Polter, MD

Irving D. Prengler, MD

Chet R. Rees, MD

Erin D. Roe, MD

Randall L. Rosenblatt, MD

Lawrence R. Schiller, MD

W. Greg Schucany, MD

wc.roberts@BaylorHealth.edu

Editorial Board

Jenny Adams, PhD

W. Mark Armstrong, MD

Raul Benavides Jr., MD

Mezgebe G. Berhe, MD

Joanne L. Blum, MD, PhD

C. Richard Boland Jr., MD

Jennifer Clay Cather, MD

James W. Choi, MD

Cristie Columbus, MD

Barry Cooper, MD

Gregory J. Dehmer, MD

R. D. Dignan, MD

Gregory G. Dimijian, MD

Michael Emmett, MD

Andrew Z. Fenves, MD

Giovanni Filardo, PhD

James W. Fleshman, MD

Editorial Staff

Managing Editor

Cynthia D. Orticio, MA, ELS

Administrative Liaison

Bradley T. Lembcke, MD

Jeffrey M. Schussler, MD

S. Michelle Shiller, DO

Michael J. Smerud, MD

Marvin J. Stone, MD

C. Allen Stringer Jr., MD

Tanya Sudia, RN, PhD

William L. Sutker, MD

Marc A. Tribble, MD

James F. Trotter, MD

Gary L. Tunell, MD

Lawrence S. Weprin, MD

F. David Winter Jr., MD

Larry M. Wolford, DMD

Scott W. Yates, MD, MBA, MS

Residents/Fellows

Aasim Afzal, MD

Timothy Ball, MD

Philip M. Edmundson, MD

Design and Production

Aptara, Inc.

Cynthia.Orticio@BaylorHealth.edu

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (ISSN 0899-8280), a peer-reviewed journal, is published quarterly (January, April, July, and October).

Proceedings is indexed in PubMed and CINAHL; the full text of articles is

available both at www.BaylorHealth.edu/Proceedings and www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov. The journal’s mission is to communicate information about the

research and clinical activities, continuing education, philosophy, and history

of Baylor Scott & White Health.

Funding for the journal is provided by the Baylor Health Care System

Foundation. Funding is also provided by donations made by the medical staff and subscribers. These donations are acknowledged each year in a

journal issue. For more information on supporting Proceedings and Baylor

Scott & White Health with charitable gifts and bequests, please call the

Foundation at 214-820-3136. Donations can also be made online at http://

give.baylorhealth.com/.

Statements and opinions expressed in Proceedings are those of the authors and

not necessarily those of Baylor Scott & White Health or its board of trustees.

Guidelines for authors are available at http://www.baylorhealth.edu/Research/

Proceedings/SubmitaManuscript/Pages/default.aspx.

January 2016

Subscriptions are offered free to libraries, physicians affiliated with Baylor,

and other interested physicians and health care professionals; donations are

suggested for print subscriptions. To add or remove your name from the mailing list, call 214-820-9996 or e-mail Cynthia.Orticio@BaylorHealth.edu.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Baylor Scientific Publications Office,

3500 Gaston Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75246.

Advertising is accepted. Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement

by Baylor Scott & White Health. For information, contact Cindy Orticio at

Cynthia.Orticio@BaylorHealth.edu.

Permission is granted to students and teachers to copy material herein for

educational purposes. Authors also have permission to reproduce their own

articles. Written permission is required for other uses and can be obtained

through Copyright.com.

Copyright © 2016, Baylor University Medical Center. All rights reserved. Printed

in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Press date: December 8, 2015.

To access Baylor’s physicians, clinical services, or educational programs, contact the Baylor Physician ConsultLine: 1-800-9BAYLOR (1-800-922-9567).

1

Clinical research studies enrolling patients through

Baylor Research Institute

Currently, Baylor Research Institute is conducting more than 800 research projects. Studies open to enrollment are listed in

the Table. To learn more about a study or to enroll patients, please call or e-mail the contact person listed.

Research area

Specific disease/condition

Contact information (name, phone number, and e-mail address)

Asthma and

pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma (adult)

Jana Holloway, RRT, CRC

Courtney Patenaude, BS

Horacio Martinez

214-818-9495

214-818-7899

214-820-0338

janahol@baylorhealth.edu

courtney.patenaude@baylorhealth.edu

horacio.martinez@baylorhealth.edu

Cancer

Breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, brain, lung, bladder, colorectal,

pancreatic, and head and neck cancer; hematological malignancies,

leukemia, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; melanoma

vaccine; bone marrow transplant

Grace Townsend

214-818-8472

cancer.trials@BaylorHealth.edu

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular events

Lorie Estrada

214-820-3416

Lorie.estrada@baylorhealth.edu

Pancreatic islet cell transplantation for type I diabetics, who either have

or have not had a kidney transplant

Kerri Purcell, RN

817-922-4640

kerri.purcell@baylorhealth.edu

Type 2; cardiac events

Trista Bachand, RN

817-922-2587

trista.bachand@baylorhealth.edu

Pancreatic islet cell transplantation for type I diabetics, who either have or

have not had a kidney transplant; high cholesterol

Kerri Purcell, RN

817-922-4640

kerri.purcell@baylorhealth.edu

Diabetes (Dallas)

Diabetes (Fort Worth)

Gastroenterology

Heart and vascular

disease (Dallas)

Inflammatory bowel disease

Dr. Themistocles Dassopoulos

469-800-7180

T.Dassopoulos@baylorhealth.edu

Aortic aneurysms, coronary artery disease, hypertension, poor leg

circulation, heart attack, heart disease, congestive heart failure, angina,

carotid artery disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, renal denervation

for hypertension, diabetes in heart disease, cholesterol disorders, heart

valves, thoracotomy pain, stem cells, critical limb ischemia, cardiac

surgery associated with kidney injury, pulmonary hypertension

Merielle Boatman

214-820-2273

MeriellH@BaylorHealth.edu

Heart and lung transplant, mechanical assist device such as LVAD

Elizabeth Owens, BA, CCRP

214-820-4015

Liz.Owens@baylorhealth.edu

Heart and vascular disease

(Fort Worth)

Atrial fibrillation, atrial fibrillation post PCI

Meagan King

817-922-2583

Meagan.king@baylorhealth.edu

Heart and vascular disease

(Legacy Heart)

At risk for heart attack/stroke; previous heart attack/stroke/PAD; cholesterol

disorders; atrial fibrillation; overweight/obese; other heart-related conditions

Angela Germany

469-800-6409

lhcresearch@baylorhealth.edu

Heart and vascular

disease (Plano)

Aortic aneurysm; coronary artery disease; renal stent for uncontrolled

hypertension; poor leg circulation; heart attack; heart disease; heart valve

repair and replacement; critical limb ischemia; repair of aortic dissections

with endografts; surgical leak repair; atrial fibrillation; heart rhythm

disorders; carotid artery disease; congestive heart failure; gene profiling

Tina Worley

469-814-4712

christina.worley1@baylorhealth.edu

Hepatology

Infectious disease

Nephrology

Neurology

Liver disease

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

HIV/AIDS

Bryan King, LVN

214-823-2533

bryan.king@ntidc.org

Hepatitis C, hepatitis B

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

Jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

Type 2 diabetes with chronic kidney disease

Lisa Mamo, RN

Dr. Harold Szerlip

214-818-2526

214-358-2300

Lisa.Mamo@BaylorHealth.edu

Harold.Szerlip@baylorhealth.edu

Stroke, migraine

Quynh Lan Doan

214-818-2522

quynh.doan@BaylorHealth.edu

Multiple sclerosis, stroke

Portland Pleasant, RN

214-820-7903

portland.pleasant@baylorhealth.edu

Cerebral aneurysms

Kennith Layton, MD

214-827-1600

KennithL@BaylorHealth.edu

Interventional stroke therapy

Tomica Harrison

214-820-2615

tomica.harrison@baylorhealth.edu

Rheumatology (9900 N.

Central Expressway)

Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus, gout,

ankylosing spondylitis

Giselle Huet

214-987-1253

ruth.huet@baylorhealth.edu

Surgery

Chronic limb ischemia, pain management with chest tubes, colon polyps,

diaphragm stimulators, and surgery as it pertains to GERD, breast cancer,

esophagus, colon, colon cancer, pancreas, lung, hernias, dialysis access,

per-oral endoscopic myology (POEM), thoracic outlet syndrome

Tammy Fisher

214-820-7221

tammyfi@BaylorHealth.edu

Bone marrow, blood stem cells

Grace Townsend

Gabrielle Ethington

214-818-8472

214-818-8326

Grace.Townsend@BaylorHealth.edu

gabriele@baylorhealth.edu

Solid organs

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

Obesity

Lorie Estrada

214-820-3416

Lorie.estrada@baylorhealth.edu

Neurosurgery

Transplantation

Weight management

Baylor Research Institute is dedicated to providing the support and tools needed for successful clinical research. To learn

more about Baylor Research Institute, please contact Kristine Hughes at 214-820-7556 or Kristine.Hughes@BaylorHealth.edu.

2

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2016;29(1):2

Meta-analysis of the effect of proton pump inhibitors on

obstructive sleep apnea symptoms and indices in patients

with gastroesophageal reflux disease

Supannee Rassameehiran, MD, Saranapoom Klomjit, MD, Nattamol Hosiriluck, MD, and Kenneth Nugent, MD

This study was designed to assess evidence for an association between

the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with proton

pump inhibitors (PPIs) and improvement in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials and prospective cohort studies to evaluate the treatment

effect of PPIs on OSA symptoms and indices in patients with GERD.

EMBASE, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials,

the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ClinicalTrials.gov

were reviewed up to October 2014. From 238 articles, two randomized

trials and four prospective cohort studies were selected. In four cohort

studies there were no differences in the apnea-hypopnea indices before

and after treatment with PPIs (standard mean difference, 0.21; 95%

confidence interval, –0.11 to 0.54). There was moderate heterogeneity

among these studies. Two cohort studies revealed significantly decreased

apnea indices after treatment (percent change, 31% and 35%), but

one showed no significant difference. A significant improvement in the

Epworth Sleepiness Scale was observed in three cohort studies and one

trial. The frequency of apnea attacks recorded in diaries was decreased

by 73% in one trial. In conclusion, available studies do not provide enough

evidence to make firm conclusions about the effects of PPI treatment on

OSA symptoms and indices in patients with concomitant GERD. Controlled

clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed to evaluate these associations. We recommend PPIs in OSA patients with concomitant GERD

to treat reflux symptoms. This treatment may improve the quality of sleep

without any effect on apnea-hypopnea indices.

T

he prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

is significantly higher in patients with obstructive sleep

apnea (OSA) (1–6), and 54% to 76% of patients with

OSA have GERD (2, 3). These two conditions share

one common risk factor, namely obesity, which increases the

risk for both apnea and reflux (7). This association may be explained by lower esophageal sphincter pressures and prolonged

esophageal relaxation following swallowing (8). These changes

could increase the frequency and severity of reflux. Nocturnal

reflux could cause sleep arousals and sleep fragmentation in

OSA patients, and acid exposure could cause edema and inflammation in the upper airway, which increase the frequency of

airway occlusions during inspiration (6). Studies supporting this

hypothesis have shown that continuous positive airway pressure

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2016;29(1):3–6

(CPAP) has antireflux effects in OSA patients (9, 10). However,

other studies have reported that the severity of OSA does not

correlate with the occurrence of reflux symptoms (11). Given

the significant morbidity and mortality of OSA, including left

ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction,

stroke, systemic hypertension, and risk of motor vehicle accidents, it is important to evaluate all factors associated with OSA

and to consider the potential benefit of treatment of factors not

directly related to upper airway anatomy (12–15). Several studies have suggested that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) improve

OSA symptoms and reduce some complications. We conducted

a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published reports

to better understand the treatment effect of GERD on the

OSA-hypopnea syndrome.

METHODS

We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central

Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ClinicalTrials.gov from database inception to

October 2014. We used the following text words as search terms:

“sleep apnea syndrome” and “proton pump inhibitor.” Our

search included articles published in English and non-English

languages. We also scanned the bibliographies of all retrieved

articles for additional relevant articles.

Two independent reviewers (S.R. and S.K.) performed

article selection, data extraction, and assessment of the risk of

bias. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) were

controlled clinical trials or observational studies that assessed

the effect of PPIs on OSA, including symptoms of daytime

somnolence, nocturnal symptoms, Epworth Sleepiness Score

(ESS), apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), apnea index, hypopnea

index, and respiratory disturbance index; 2) reported concomitant GERD in patients with OSA; and 3) provided adequate

data to extract the outcomes. We excluded studies that reported

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences

Center, Lubbock, Texas.

Corresponding author: Supannee Rassameehiran, MD, Department of Internal

Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Science Center, 3601 4th Street, Lubbock,

TX 79430 (e-mail: Supannee.Rassameehiran@ttuhsc.edu).

3

only the prevalence of GERD in OSA patients, patients who

were treated with CPAP and PPIs, and OSA patients without

underlying GERD who were treated with PPIs. If multiple

updates of the same data were found, we used the most recent

version for analysis. From each study, we abstracted the study

design, setting, population characteristics (including sex, age,

race or ethnicity, baseline body mass index [BMI], and baseline AHI), patient eligibility and exclusion criteria, number of

patients, type of PPIs used, treatment duration, and method of

outcome determination.

Two reviewers (S.R. and S.K.) independently assessed the

quality of each trial by using a tool developed by the Cochrane

Collaboration (16). Each trial was given an overall summary

assessment of low, unclear, or high risk of bias. We adapted

existing tools to assess the quality of observational studies. The

strength of evidence for outcomes was graded as high, moderate, low, or very low according to the approach of the GRADE

working group (17).

AHIs in patients before treatment versus after treatment

were evaluated. Statistical analysis was conducted with Review

Manager (RevMan Version 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration,

The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The

chi-square test and I2 statistic were used to address heterogeneity

among studies. The results of the studies were pooled, and an

overall standard mean difference with 95% confidence intervals

(CIs) was obtained using generic inverse variance weighting and

a random effects method.

RESULTS

The electronic and manual searches yielded 238 total citations (Figure 1). We identified 20 potentially relevant full-text

articles and analyzed six published articles, published as full

papers, which met our inclusion criteria. No additional abstracts

were identified by hand searches of conference proceedings.

Figure 1. Literature search strategy.

4

Two controlled clinical trials compared the effects of PPIs

and placebos on OSA (18, 19). The first trial was a double-blind,

randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial (18). This trial

recruited 57 patients with ESS > 8 (mean ESS ± SD: 14 ± 3.5),

mild to moderate OSA (mean AHI ± SD: 10 ± 8.4), and typical

symptoms and finding of GERD between February 2004 and

August 2006 and treated them with either placebo or pantoprazole 40 mg once daily followed by a 2-week washout period

and then a 2-week crossover treatment period. ESS decreased

with pantoprazole (–1.8, 95% CI: –3.0 to –0.5) compared with

placebo (–1.5, 95% CI: –2.1 to –0.4, P = 0.04). There were

no significant changes in sleep-related quality of life using the

Functional Outcomes Sleep Questionnaire or reaction times,

tested by having subjects push a button as fast as they could

whenever they saw a clock begin counting up from 0000 (18).

The trial had a low risk of bias.

The second trial included 20 patients with confirmed OSA

(mean AHI: 30.9) by overnight polysomnography and confirmed GERD by 24 h esophageal pH electrode (19). The patients were randomly divided into two groups and treated with

omeprazole 20 mg or placebo 30 minutes before breakfast and

before dinner (n = 10 each group) for 6 weeks. The number of

apnea attacks, which were defined as a symptom of nocturnal

choking, gasping, or snoring that awakened the patients, was

recorded by patients in diaries. The frequency of apnea attacks

decreased 73% in the treatment group compared to their basal

period and in the treatment group compared with the placebo

group in the sixth week (P < 0.001). This trial had an unclear

risk of bias due to unclear reporting of randomization and allocation concealment techniques.

The four prospective cohort studies analyzed in this review

included 91 patients who had OSA and GERD. The main

characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1. Four

studies (20–23) reported data on AHI; three studies (20, 21,

23) provided data on apnea index, and three

studies (20, 22) reported data on ESS. These

trials had methodological limitations that

led to an unclear risk of bias since all studies

were single-center prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, used

patients’ baseline parameters as the control,

and had small sample sizes.

Four observational studies compared the

effects of PPI use on AHI in patients before

treatment versus after treatment (20–23).

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. The standard

mean difference was 0.21 (95% CI: –0.11 to

0.54) (Table 2). Heterogeneity was minimal

in the studies (P for heterogeneity = 0.31,

I 2 = 17%).

Three observational studies (20, 21, 23)

compared the effects of PPI use on the apnea

index in patients before treatment versus after treatment. Two studies reported a statistically significant improvement in the apnea

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 29, Number 1

Table 1. Characteristics of obstructive sleep apnea patients using proton pump inhibitors

First author

Treated Control Mean

age Women

BMI

cases cases

Mean Mean

(years)

(n)

(kg/m2) ESS

(n)

(n)

AHI

Proton pump

inhibitor

(40 mg/day)

Randomized controlled trials

Suurna

28*

29

51

33

31

14

10

Pantoprazole

Bortolotti

10

10

55

3

30

NR

30.9

Omeprazole

statistically significant mean change in ESS

(21). Two studies reported decreased snoring as assessed by bed partners (20, 21),

and one reported decreased upper airway

inflammation based on fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy examinations before and after

treatment (22).

DISCUSSION

The articles used in this systematic reFriedman

29

–

45

17

33

14.2

38

Esomeprazole

view and meta-analysis studied the effects

of PPIs on OSA indices, daytime sleepiness,

Steward

27

–

49

9

33

12.9 15.4 Pantoprazole

and other nocturnal symptoms. This analysis

Orr

25

–

43

7

31

12

9.3

Rabeprazole

included two randomized controlled trials

Senior

10

–

18–59

0

NR

NR

62

Omeprazole

and four observational prospective studies.

*Crossover design.

The studies identified a modest benefit of

AHI indicates apnea-hypopnea index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; NR, not reported; –, not applicable.

PPI therapy on daytime somnolence but

did not identify any significant difference

in apnea or hypopnea indices. The effect on

Table 2. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on apnea and hypopnea indices*

the ESS was modest and not associated with

any change in sleep-related quality of life or

Before treatment

After treatment

Study or

Std. mean difference IV,

reaction times. The other trial reported a

subgroup

Mean SD Total Mean SD Total Weight

random, 95% CI

reduction in nocturnal symptoms based on

Friedman (2007) 37.9 19.1 29

28.8 11.5 29

30.3%

0.57 (0.04, 1.10)

diary records. The symptoms are not necesOrr (2009)

9.3

4.7 25

9.1

8.7 25

27.8%

0.03 (–0.53, 0.58)

sarily unique to OSA and could have other

Steward (2004)

15.4 11.7 27

16.2

8.0 27

29.6%

–0.08 (–0.61, 0.45)

causes during the night. The results with

Senior (2001)

62.0 30.5 10

46.0 37.0 10

12.2%

0.45 (–0.44, 1.34)

AHI comparisons should be interpreted

with caution, due to the clinical heterogeTotal (95% CI)

91

91 100.0%

0.21 (–0.11, 0.54)

neity among studies and unclear risk of bias.

*Heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.02; Chi2 = 3.62; df = 3 (P = 0.31); F = 17%. Test for overall effect: Z = 1.28 (P = 0.20).

These limitations are discussed more below.

There are several potential explanations

for the lack of benefit with PPI therapy in patients with OSA.

index (mean 5.9 ± 7.2 to 3.8 ± 4.7, P = 0.04 in the study by

GERD and OSA are relatively common problems; they could

Friedman [20]; mean 45 [range: 10–108] to 31 [range: 1–78],

occur coincidentally in some patients and have no causal reP = 0.04 in the study by Senior [23]). However, the study

lationships. Shepherd and coworkers reported detailed studies

reported by Steward revealed no statistically significant differin eight patients with OSA undergoing polysomnography with

ence between the two groups (mean change 1.4, 95% CI: –0.1

esophageal manometry and pH monitoring (8). During the

to 2.9, P = 0.07) (21). No baseline mean apnea index in this

recording phase without CPAP, the patients had 70 ± 39 respirastudy was available.

tory events per hour and 2.7 ± 1.8 reflux events per hour. The

Three observational studies (20–22) compared the effects

number of obstructive events in this study appeared to have little

of PPI use on ESS in patients before treatment versus after

or no effect on reflux events. In addition, overlapping symptoms

treatment. Two studies reported statistically significant imcould confuse this situation and an y conclusions about cause

provement of ESS and provided numerical scores for the ESS

and effect relationships. However, very frequent reflux events

before and after treatment (Figure 2). One study reported a

could influence OSA and sleep quality through central nervous

system arousals, chronic lower esophageal inflammation with

vagal stimulation, and laryngeal inflammation with changes in

the upper airway dynamics.

There might be a threshold in the number of reflux events

required before any effect occurs, and the duration of these

two syndromes could influence any interaction. The treatment

of GERD with PPIs may require more time than most studies

have used in their study design. An adequate treatment period

for PPIs to completely resolve anatomic changes caused by acid

reflux–related injury can take up to 6 months; however, only

one study in this review reached that period of time (20, 24,

25). Another possibility is that PPI treatment may truly improve

Figure 2. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Prospective trials

January 2016

Effect of proton pump inhibitors on obstructive sleep apnea symptoms and indices in patients with GERD

5

OSA symptoms, but this effect would be important only in

patients with very frequent reflux events.

In addition, treatment with CPAP could have several possible effects on GERD which might influence results in studies

on GERD in patients with OSA. First, CPAP may have no

effect, or CPAP could change intrathoracic pressure dynamics

and reduce reflux. This effect most likely would occur at the

gastroesophageal junction. CPAP could also change esophageal

motility and improve esophageal clearance. Shepherd reported

that CPAP increased the nadir pressure in the lower esophagus

and reduced the duration of the lower esophageal sphincter

relaxation time (8). Again, these effects are important only in

patients with frequent reflux events.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, our analysis included only six studies with small numbers of patients.

Second, there was heterogeneity across the studies in the analysis of AHI reduction. This can be partly explained by different study designs, types of PPIs, and duration of treatment.

Most studies had design limitations, including small sample

size and single-center cohort studies, which resulted in a low

strength of evidence. Observational studies that used patients’

baseline parameters as controls may be compromised by placebo effects in addition to other design limitations. The ESS is

a self-assessment scale that represents only a predilection to fall

asleep and is not a specific outcome in OSA patients. Other

symptoms reported in sleep diaries may not be specific for OSA

and may introduce another source of variability in study results.

Patients with GERD have reduced health-related quality of life,

and this is associated with nocturnal reflux symptoms (26, 27).

We used a random effects method for analysis to account for

heterogeneity among studies, and we attempted to minimize the

risk of missing relevant studies by searching multiple databases,

bibliographies, and trial registries.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

6

Ing AJ, Ngu MC, Breslin AB. Obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med 2000;108(Suppl 4a):120S–125S.

Green BT, Broughton WA, O’Connor JB. Marked improvement in

nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure.

Arch Intern Med 2003;163(1):41–45.

Valipour A, Makker HK, Hardy R, Emegbo S, Toma T, Spiro SG. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in subjects with a breathing sleep disorder.

Chest 2002;121(6):1748–1753.

Guda N, Partington S, Vakil N. Symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux, arousals and sleep quality in patients undergoing polysomnography

for possible obstructive sleep apnoea. Alimentary Pharm Therapeutics

2004;20(10):1153–1159.

Graf KI, Karaus M, Heinemann S, Körber S, Dorow P, Hampel KE.

Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Z

Gastroenterol 1995;33(12):689–693.

Penzel T, Becker HF, Brandenburg U, Labunski T, Pankow W, Peter JH.

Arousal in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux and sleep apnoea. Eur

Respir J 1999;14(6):1266–1270.

Janson C, Gislason T, De Backer W, Plaschke P, Björnsson E, Hetta J,

Kristbjarnason H, Vermeire P, Boman G. Daytime sleepiness, snoring

and gastro-oesophageal reflux amongst young adults in three European

countries. J Intern Med 1995;237(3):277–285.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

Shepherd K, Hillman D, Holloway R, Eastwood P. Mechanisms of

nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux events in obstructive sleep apnea.

Sleep Breath 2011;15(3):561–570.

Kerr P, Shoenut JP, Millar T, Buckle P, Kryger MH. Nasal CPAP reduces

gastroesophageal reflux in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest

1992;101(6):1539–1544.

Zanation AM, Senior BA. The relationship between extraesophageal reflux

(EER) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Sleep Med Rev 2005;9(6):453–458.

Kim HN, Vorona RD, Winn MP, Doviak M, Johnson DA, Ware JC.

Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and the severity of

obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome are not related in sleep disorders center

patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21(9):1127–1133.

Terán-Santos J, Jiménez-Gómez A, Cordero-Guevara J; Cooperative

Group Burgos-Santander. The association between sleep apnea and the

risk of traffic accidents. N Engl J Med 1999;340(11):847–851.

Hla KM, Young TB, Bidwell T, Palta M, Skatrud JB, Dempsey J. Sleep

apnea and hypertension. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med

1994;120(5):382–388.

Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D’Agostino

RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleepdisordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large communitybased study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA 2000;283(14):1829–1836.

Caples SM, Somers VK. Sleep-disordered breathing and atrial fibrillation.

Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009;51(5):411–415.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD,

Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group;

Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool

for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A.

GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64(4):380–382.

Suurna MV, Welge J, Surdulescu V, Kushner J, Steward DL. Randomized

placebo-controlled trial of pantoprazole for daytime sleepiness in GERD

and obstructive sleep disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

2008;139(2):286–290.

Bortolotti M, Gentilini L, Morselli C, Giovannini M. Obstructive sleep

apnoea is improved by a prolonged treatment of gastrooesophageal reflux

with omeprazole. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38(2):78–81.

Friedman M, Gurpinar B, Lin HC, Schalch P, Joseph NJ. Impact of

treatment of gastroesophageal reflux on obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea

syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2007;116(11):805–811.

Steward DL. Pantoprazole for sleepiness associated with acid reflux and obstructive sleep disordered breathing. Laryngoscope 2004;114(9):1525–1528.

Orr WC, Robert JJ, Houck JR, Giddens CL, Tawk MM. The effect of

acid suppression on upper airway anatomy and obstruction in patients

with sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Sleep Med

2009;5(4):330–334.

Senior BA, Khan M, Schwimmer C, Rosenthal L, Benninger M.

Gastroesophageal reflux and obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope

2001;111(12):2144–2146.

Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux

symptoms improve before changes in physical findings. Laryngoscope

2001;111(6):979–981.

Koufman JA, Aviv JE, Casiano RR, Shaw GY. Laryngopharyngeal reflux:

position statement of the Committee on Speech, Voice, and Swallowing

Disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck

Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;127(1):32–35.

Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, Ganoczy D, Chee E, Lee C, Revicki D. The

impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(1):45–52.

Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med

1998;104(3):252–258.

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 29, Number 1

Serum hyperchloremia as a risk factor for acute kidney

injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial

infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention

Nachiket Patel, MD, Sarah M. Baker, BSN, RN, Ryan W. Walters, MS, Ajay Kaja, MBBS, Vimalkumar Kandasamy, MBBS,

Ahmed Abuzaid, MBChB, and Ariel M. Modrykamien, MD

A high serum chloride concentration has been associated with the development of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. However, the

association between hyperchloremia and acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients admitted with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is unknown. A

retrospective analysis of consecutive patients admitted with the diagnosis

of STEMI and treated with PCI was performed. Subjects were classified

as having hyper- or normochloremia based upon their admission serum

chloride level. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were employed

for the primary and secondary outcomes. The primary analysis evaluated whether high serum chloride on admission was associated with the

development of AKI after adjusting for age, diabetes mellitus, admission

systolic blood pressure, contrast volume used during angiography, Killip

class, and need for vasopressor therapy or intraaortic balloon pump. The

secondary analyses evaluated whether high serum chloride was associated with sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Of 291 patients

(26.1% female, mean age of 59.9 ± 12.6 years, and mean body mass

index of 29.3 ± 6.1 kg/m2), 25 (8.6%) developed AKI. High serum chloride

on admission did not contribute significantly to the development of AKI

(odds ratio, 95%; confidence interval, 0.90 to 1.24). In addition, serum

chloride on admission was not significantly associated with sustained

ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation after adjusting for demographic and

clinical covariates. In conclusion, our study demonstrated no association

between baseline serum hyperchloremia and an increased risk of AKI in

patients admitted with STEMI treated with PCI.

C

oronary angiography is the third leading cause of acute

kidney injury (AKI) among hospitalized patients (1,

2). Several risk factors for the development of radiocontrast-induced kidney injury have been identified,

including diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and heart

failure (3–5). Since AKI after angiography has been associated

with a variety of adverse clinical outcomes, such as increased

mortality, cardiovascular events, and prolonged hospitalization,

several lines of investigation have focused on finding risk factors

to predict its occurrence (6, 7). Particularly, the relation between

serum chloride concentration and the development of AKI has

been gaining increasing attention. Among critically ill patients,

the presence of a high chloride concentration prior to intensive care unit (ICU) admission has been associated with AKI.

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2016;29(1):7–11

Furthermore, a positive correlation between chloride levels and

severity of AKI has also been described (8). Recent investigations have shown that baseline hyperchloremia >110 mEq/L is

associated with higher hospital mortality in critically ill septic

patients (9). Other recently published articles have revealed

that the administration of chloride-enriched fluids is associated with renal vasoconstriction and the subsequent decline of

glomerular filtration rate (10, 11). Consequently, strategies of

fluid resuscitation using chloride-restrictive solutions have been

studied, demonstrating a lower incidence of AKI compared with

chloride-liberal fluid strategies (12). Despite the aforementioned

data, many gaps in our understanding of the relation between

serum chloride levels and consequent AKI still remain. Specifically, whether high chloride concentration is a risk factor for the

development of AKI in patients undergoing coronary angiography is currently unknown. This study addressed this question

by analyzing data from a consecutive series of patients who

underwent emergent cardiac catheterization due to ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) at our institution.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center retrospective study to assess the

association between serum hyperchloremia at hospital admission

and AKI in patients admitted with STEMI treated with emergent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). After approval

by the institutional review board of the Creighton University

School of Medicine, we collected data from patients admitted with STEMI who underwent emergent PCI from January

2003 to June 2010. Patients whose admission serum sodium

was outside the physiological range, <135 and >145 mEq/L,

were excluded. Hyperchloremia was defined as a serum chloride

From the Division of Cardiology University of Florida College of Medicine,

Jacksonville (Patel); the Division of Clinical Research and Evaluative Sciences

(Walters) and Division of General Internal Medicine (Kaja, Kandasamy, Abuzaid),

Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, Nebraska; Intensive Care Unit,

Alegent-Creighton Health, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska

(Baker); and Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Baylor University

Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, Texas (Modrykamien).

Corresponding author: Ariel Modrykamien, MD, Medical Director, Respiratory

Care Services, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Baylor University

Medical Center at Dallas, 3600 Gaston Avenue, Suite 960, Dallas, TX 75246

(e-mail: ariel.modrykamien@baylorhealth.edu).

7

as discriminative ability via C-statistic. Perfect discrimination

concentration >75% of the serum sodium concentration on the

yields a C-statistic of 1.0, whereas a C-statistic of 0.50 indicates

electrolyte panel obtained at the time of admission. Normochlorthat discrimination was no better than chance. For analysis,

emia was defined as a serum chloride concentration ≤75% of

continuous variables were centered near their mean. All analyses

the serum sodium concentration (13). Electrolyte measurements

were performed using SAS v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc); P < .05

were performed using the Dimension Vista® 500 (Siemens, Newwas considered statistically significant for all analyses.

ark, DE). Demographic, clinical, procedural, and outcome data

were collected. Importantly, patients with end-stage renal disease

RESULTS

undergoing intermittent hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, as

Of the 401 patients admitted with STEMI and treated with

well as pregnant women, were excluded from this study.

PCI between January 2003 and June 2010, 105 had abnormal

The primary outcome of interest was the development of

serum sodium on admission (104 patients <135 mEq/L and 1

AKI during the hospitalization, within 7 days after PCI. AKI

patient >145 mEq/L); these patients were excluded from analywas defined based on changes in creatinine concentration, acsis. Of the remaining 296 patients, 5 did not have complete

cording to criteria of the Acute Kidney Injury Network (14).

data. Thus, analyses included 291 patients, with 26.1% female,

This classification and staging system of AKI states that the

a mean age of 59.9 ± 12.6 years, and a mean body mass index

elevation of baseline creatinine by 1.5 to 1.9 times, or an absoof 29.3 ± 6.1 kg/m2.

lute increase of 0.3 mg/dL from the baseline (both within 48

hours of a known baseline), constitute the first stage of AKI.

Descriptive statistics for demographic and clinical variThe secondary endpoint was the development of either susables are presented in Table 1. Of the 291 patients, 25 (8.6%)

tained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation durdeveloped AKI and had significantly greater corrected anion

ing the hospitalization. Sustained ventricular tachycardia was

gap, as well as higher rates of intraaortic balloon pump use

defined as lasting >30 seconds or requiring termination due to

and cardiogenic shock, and were more likely to have higher

hemodynamic instability in <30 seconds (15).

Killip class compared with patients who did not develop AKI.

Continuous demographic and clinical variables are presented as mean ±

Table 1. Univariate analyses of demographic and clinical covariates

standard deviation, whereas categorical

variables are presented as frequency and

Acute kidney injury

percentage. Differences in these variables

No (n = 266)

Yes (n = 25)

P

between patients who developed AKI and

Age (years)

0.08

patients who did not were evaluated using

59.5 ± 12.5

64.1 ± 13.7

independent-samples t tests for continu2

0.30

Body mass index (kg/m )

29.2 ± 6.0

30.5 ± 6.2

ous variables and Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s

Admit systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

0.7

122.4 ± 19.6

120.7 ± 22.1

exact tests for categorical variables.

Admit sodium (mEq/L)

0.99

137.9 ± 2.0

137.9 ± 1.9

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were employed for the primary and

Admit chloride (mEq/L)

0.65

104.0 ± 3.4

104.2 ± 3.0

secondary analyses. The primary analysis

Admit glomerular filtration rate (mL/min)

1.0

83.3 ± 26.1

83.3 ± 41.6

evaluated whether serum chloride on adContrast volume (mL)

0.89

171.2 ± 72.2

173.3 ± 91.8

mission was associated with the developCorrected

anion

gap

(mEq/L)

<0.05

10.3 ± 2.8

12.5 ± 3.4

ment of AKI in patients admitted with

STEMI after adjusting for age, diabetes

Female

68 (26%)

8 (32%)

0.45

mellitus, contrast volume (iopamidol 755

Smoker

142 (53%)

12 (48%)

0.86

mg/mL, Bracco Diagnostics, NJ) adminHypertension

144 (54%)

17 (68%)

0.41

istered, Killip class, use of pressor medicaDiabetes mellitus

4 1 (15%)

7 (28%)

0.05

tions or intraaortic balloon pump, whether

the patient suffered cardiogenic shock durHyperlipidemia

127 (48%)

14 (56%)

1.00

ing hospitalization, corrected anion gap, as

Use of pressors

9 (3%)

3 (12%)

<0.05

well as systolic blood pressure, glomerular

Intraaortic balloon pump (used)

12 (5%)

7 (28%)

<0.05

filtration rate, and systolic blood pressure

Killip class

<0.05

on admission. Two secondary analyses evaluated whether serum chloride on admission

I

227 (84%)

13 (52%)

was associated with sustained ventricular

II

24 (9%)

4 (16%)

tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation after

III

11 (4%)

3 (12%)

adjusting for the same demographic and

IV

7 (4%)

5 (20%)

clinical covariates listed above.

The accuracy of the logistic regresShock

16 (6%)

8 (32%)

<0.05

sion models was assessed by Hosmer

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or as n (%).

and Lemeshow goodness of fit as well

8

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 29, Number 1

subgroup analyses aimed at studying particular ICU patients, such as those with

trauma, abdominal surgery, and cardio95% CI for OR

vascular diseases, revealed similar results.

Lower

Upper

Variable

Coefficient

SE

OR

AKI in the context of hyperchloremia

Intercept

–2.76

1.17

0.06

0.11

10.60

could be explained by several physiologic

mechanisms. Wilcox et al (10) used an

Age (0 = 60)

0.03

0.02

1.03

0.99

1.07

animal model to demonstrate the speDiabetes mellitus

0.50

0.57

1.64

0.54

4.99

cific vasoconstrictive effect of chloride

Use of pressors

0.00

0.94

1.00

0.16

6.36

in renal vessels, with subsequent reduction of cortical perfusion and increase of

Intraaortic balloon pump

1.22

0.77

3.38

0.75

15.29

inflammatory mediators. Furthermore,

Killip class (reference = IV)

Wu et al (16) specifically assessed the efI

–0.65

1.04

0.52

0.07

4.00

fect of chloride in the inflammatory casII

0.03

1.04

1.03

0.13

7.88

cade. Strikingly, patients randomized to

receive saline 0.9% had higher C-reactive

III

0.54

1.13

1.72

0.19

15.78

protein levels and higher rates of systemic

Shock

0.96

0.84

2.60

0.50

13.62

inflammatory response syndrome comAdmit sodium (0 = 135)

0.01

0.12

1.01

0.79

1.28

pared with subjects treated with Ringer’s

Admit glomerular filtration rate (0 = 85)

0.00

0.01

1.00

0.99

1.02

solutions.

Based on the aforementioned data, reAdmit systolic blood pressure (0 = 121)

0.01

0.01

1.01

0.99

1.03

cent

investigations attempted to compare

Control volume (0 = 172)

0.00

0.00

1.00

0.99

1.01

different fluid resuscitation strategies in

Corrected anion gap (0 = 10)

0.25

0.09

1.28*

1.08

1.52

critically ill patients. Particularly, Yunos

Admit chloride (0 = 105)

0.05

0.08

1.06

0.90

1.24

et al (12) compared a chloride-restrictive

vs a chloride-liberal fluid strategy in

*P < 0.05.

a before-and-after study. As expected,

CI indicates confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

patients in the chloride-restrictive arm

received less chloride (496 vs 694 mmol

per patient) and had lower rates of AKI. Nevertheless, this study

Nonsignificant clinical covariates were included in the multidid not report serum chloride levels in each arm, limiting the

variable analysis due to theoretical considerations.

interpretation of whether the presented outcome was directly

Final model results from the multivariable logistic regression

associated with chloride concentrations.

analysis for AKI are presented in Table 2. The logistic model fit

2

Despite the studies demonstrating adverse renal outthe data well (χ 8 = 6.90, P = .55) with good discrimination

comes associated with hyperchloremia and administration of

(C = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.70 to 0.91). After

chloride-liberal fluids, our study did not show an association

adjustment, serum chloride on admission did not contribute

between hyperchloremia and the development of post-PCI AKI.

significantly to the development of AKI (odds ratio, 95%;

However, these results seem to be in line with prior studies

CI = 0.90 to 1.24). In addition, serum chloride on admisexamining the effect of the type of fluid administration on

sion was not significantly associated with sustained ventricular

the development of AKI in patients undergoing coronary antachycardia or fibrillation after adjusting for demographic and

giography, none of which demonstrated any relation between

clinical covariates.

the concentration of chloride administered in the intravenous

fluid and the development of AKI. Specifically, Mueller et al

DISCUSSION

(17) found that hydration with 0.9% saline before and after

This study shows the following results: 1) hyperchloremia

exposure to contrast media significantly reduced the incidence

upon hospital admission is not associated with the developof contrast-induced nephropathy compared with 0.45% saline

ment of AKI post-PCI, and 2) hyperchloremia is not associated

with dextrose in patients undergoing coronary angiography. In

with severe arrhythmias post-PCI, such as sustained ventricular

addition, two prospective studies comparing 0.9% saline and

tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation.

isotonic bicarbonate in patients who received contrast media for

Several studies suggest adverse outcomes associated with the

coronary angiography found no difference in the development

presence of serum hyperchloremia. Specifically, Zhang et al (8)

of contrast-induced nephropathy (18, 19). The role of chloride

retrospectively evaluated a consecutive series of patients admitin the development of AKI in patients undergoing coronary

ted in a mixed ICU for the presence of hyperchloremia and

angiography and PCI remains to be clarified.

its association with AKI. Interestingly, patients with higher

We focused our study on patients with STEMI treated

chloride concentrations had a statistically significant associawith PCI. This particular group has an increased incidence

tion with the development of AKI (chloride concentrations

of AKI postprocedure, mostly due to contrast nephrotoxicity.

of 118.8 ± 8.1 vs 107.9 ± 5.4 mmol/L; P < 0.001). Notably,

Table 2. Multivariable logistic regression results for development of acute kidney injury

January 2016

Serum hyperchloremia as a risk factor for acute kidney injury in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI

9

As a matter of fact, the rate of kidney injury in this patient

population ranges from 2% to 30%, being higher in individuals with baseline creatinine >2 mg/dL prior to the procedure

(3, 20). Previous studies revealed a higher incidence of AKI

postangiography in specific populations, such as those with

preexisting renal disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and

those receiving large intraprocedural volumes of hyperosmolar contrast (21–25). However, we were unable to find these

associations after adjustment for some of those variables. It

is possible that our sample was not large enough to find the

aforementioned results.

We attempted to assess whether the presence of hyperchloremia was associated with severe cardiac arrhythmias, namely sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Studies in animal

models and humans showed associations between electrolyte

disturbances and cardiac arrhythmias. The cardiac implications

of potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium alterations have

been extensively described (26–32). Nevertheless, no prior reports have focused on the eventual arrhythmogenic effects of

abnormal chloride concentrations. Our study revealed no significant differences in the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias

associated with chloride levels.

The present study has many strengths. First, this is the first

report that aimed to assess the relationship between baseline

chloride concentrations and kidney function post-PCI. Second,

this is the first study to address the impact of hyperchloremia

in cardiac arrhythmias. Although we did not find any association between serum chloride levels and arrhythmias, our study

may be hypothesis generating for further research in this area.

Third, variables included in our statistical analysis were obtained from prior validated models, which showed association

between each of them and the development of contrast-induced

nephropathy (33).

Despite its strengths, our study also presents several limitations. First, being a retrospective study, it is likely that we

incurred a selection bias. The lack of relevant information on

nine patients affected the completeness of our dataset. Therefore, it is possible that our results may have changed had these

subjects been included. Second, the small number of patients

could have led to underestimation of important differences in

clinical outcomes, such as incidence of cardiac arrhythmias.

Last, a number of relevant factors, such as hemoglobin A1c

levels, ventricular ejection fraction, and use of prior nephrotoxic

medications, were not included in our dataset. These meaningful factors could have altered the incidence of AKI without our

knowledge.

1.

2.

3.

4.

10

Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced

by contrast medium. N Engl J Med 2006;354(4):379–386.

Finn WF. The clinical and renal consequences of contrast-induced

nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21(6):i2–i10.

McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O’Neill WW. Acute

renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and

relationship to mortality. Am J Med 1997;103(5):368–375.

Bartholomew BA, Harjai KJ, Dukkipati S, Boura JA, Yerkey MW, Glazier

S, Grines CL, O’Neill WW. Impact of nephropathy after percutaneous

coronary intervention and a method for risk stratification. Am J Cardiol

2004;93(12):1515–1519.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

McCullough PA, Stacul F, Becker CR, Adam A, Lameire N, Tumlin

JA, Davidson CJ; CIN Consensus Working Panel. Contrast-Induced

Nephropathy (CIN) Consensus Working Panel: executive summary.

Rev Cardiovasc Med 2006;7(4):177–197.

Weisbord SD, Chen H, Stone RA, Kip KE, Fine MJ, Saul MI, Palevsky

PM. Associations of increases in serum creatinine with mortality and

length of hospital stay after coronary angiography. J Am Soc Nephrol

2006;17(10):2871–2877.

James MT, Samuel SM, Manning MA, Tonelli M, Ghali WA, Faris P,

Knudtson ML, Pannu N, Hemmelgarn BR. Contrast-induced acute

kidney injury and risk of adverse clinical outcomes after coronary

angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv

2013;6(1):37–43.

Zhang Z, Xu X, Fan H, Li D, Deng H. Higher serum chloride concentrations are associated with acute kidney injury in unselected critically ill

patients. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:235.

Neyra JA, Canepa-Escaro F, Li X, Manllo J, Adams-Huet B, Yee J, Yessayan

L; Acute Kidney Injury in Critical Illness Study Group. Association of

hyperchloremia with hospital mortality in critically ill septic patients. Crit

Care Med 2015;43(9):1938–1944.

Wilcox CS. Regulation of renal blood flow by plasma chloride. J Clin

Invest 1983;71(3):726–735.

Wilcox CS. Renal haemodynamics during hyperchloraemia in the

anaesthetized dog: effects of captopril. J Physiol 1988;406:27–34.

Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Hegarty C, Story D, Ho L, Bailey M. Association between a chloride-liberal vs chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid

administration strategy and kidney injury in critically ill adults. JAMA

2012;308(15):1566–1572.

Durward A, Skellett S, Mayer A, Taylor D, Tibby SM, Murdoch IA.

The value of the chloride:sodium ratio in differentiating the aetiology of

metabolic acidosis. Intensive Care Med 2001;27(5):828–835.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG,

Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve

outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2007;11(2):R31.

Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer

M, Gregoratos G, Klein G, Moss AJ, Myerburg RJ, Priori SG, Quinones

MA, Roden DM, Silka MJ, Tracy C, Smith SC Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD,

Antman EM, Anderson JL, Hunt SA, Halperin JL, Nishimura R, Ornato

JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres

C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey

A, Tamargo JL, Zamorano JL. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of

sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2006;114(10):e385–e484.

Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, Repas K, Delee R, Yu S, Smith B,

Banks PA, Conwell DL. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic

inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9(8):710–717.e1.

Mueller C, Buerkle G, Buettner HJ, Petersen J, Perruchoud AP, Eriksson

U, Marsch S, Roskamm H. Prevention of contrast media–associated

nephropathy: randomized comparison of 2 hydration regimens in

1620 patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. Arch Intern Med

2002;162(3):329–336.

Maioli M, Toso A, Leoncini M, Gallopin M, Tedeschi D, Micheletti

C, Bellandi F. Sodium bicarbonate versus saline for the prevention

of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with renal dysfunction

undergoing coronary angiography or intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol

2008;52(8):599–604.

Adolph E, Holdt-Lehmann B, Chatterjee T, Paschka S, Prott A, Schneider

H, Koerber T, Ince H, Steiner M, Schuff-Werner P, Nienaber CA. Renal

Insufficiency Following Radiocontrast Exposure Trial (REINFORCE): a

randomized comparison of sodium bicarbonate versus sodium chloride

hydration for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy. Coron

Artery Dis 2008;19(6):413–419.

Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, Singh M,

Bell MR, Barsness GW, Mathew V, Garratt KN, Holmes DR Jr. Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous

coronary intervention. Circulation 2002;105(19):2259–2264.

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 29, Number 1

21. Stacul F, van der Molen AJ, Reimer P, Webb JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos

SK, Almén T, Aspelin P, Bellin MF, Clement O, Heinz-Peer G; Contrast

Media Safety Committee of European Society of Urogenital Radiology

(ESUR). Contrast induced nephropathy: updated ESUR Contrast Media

Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol 2011;21(12):2527–2541.

22. Parfrey PS, Griffiths SM, Barrett BJ, Paul MD, Genge M, Withers J,

Farid N, McManamon PJ. Contrast material–induced renal failure in

patients with diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, or both. A prospective

controlled study. N Engl J Med 1989;320(3):143–149.

23. Seeliger E, Sendeski M, Rihal CS, Persson PB. Contrast-induced

kidney injury: mechanisms, risk factors, and prevention. Eur Heart J

2012;33(16):2007–2015.

24. Heinrich MC, Kuhlmann MK, Grgic A, Heckmann M, Kramann B, Uder

M. Cytotoxic effects of ionic high-osmolar, nonionic monomeric, and

nonionic iso-osmolar dimeric iodinated contrast media on renal tubular

cells in vitro. Radiology 2005;235(3):843–849.

25. Tehrani S, Laing C, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Contrast-induced acute

kidney injury following PCI. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43(5):483–490.

26. Schulman M, Narins RG. Hypokalemia and cardiovascular disease. Am

J Cardiol 1990;65(10):4E–9E.

January 2016

27. Gettes L, Surawicz B. Effects of low and high concentrations of potassium

on the simultaneously recorded Purkinje and ventricular action potentials

of the perfused pig moderator band. Circ Res 1968;23(6):717–729.

28. Hohnloser SH, Verrier RL, Lown B, Raeder EA. Effect of hypokalemia

on susceptibility to ventricular fibrillation in the normal and ischemic

canine heart. Am Heart J 1986;112(1):32–35.

29. Ettinger PO, Regan TJ, Oldewurtel HA. Hyperkalemia, cardiac conduction, and the electrocardiogram: a review. Am Heart J 1974;88(3):360–371.

30. Leitch SP, Brown HF. Effect of raised extracellular calcium on characteristics of the guinea-pig ventricular action potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol

1996;28(3):541–551.

31. Keller PK, Aronson RS. The role of magnesium in cardiac arrhythmias.

Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1990;32(6):433–448.

32. El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis.

Cardiol J 2011;18(3):233–245.

33. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, Fahy M, Mintz

GS, Lansky AJ, Moses JW, Stone GW, Leon MB, Dangas G. A simple

risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2004;44(7):1393–1399.

Serum hyperchloremia as a risk factor for acute kidney injury in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI

11

Frequency of fluid overload and usefulness of bioimpedance

in patients requiring intensive care for sepsis syndromes

Timothy R. Larsen, DO, Gurbir Singh, MD, Victor Velocci, MD, Mohamed Nasser, MD, and Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH

Guideline-directed therapy for sepsis calls for early fluid resuscitation.

Often patients receive large volumes of intravenous fluids. Bioimpedance

vector analysis (BIVA) is a noninvasive technique useful for measuring

total body water. In this prospective observational study, we enrolled

18 patients admitted to the intensive care unit for the treatment of

sepsis syndromes. Laboratory data, clinical parameters, and BIVA were

recorded daily. All but one patient experienced volume overload during

the course of treatment. Two patients had >20 L of excess volume.

Volume overload is clinically represented by tissue edema. Edema is

not a benign condition, as it impairs tissue oxygenation, obstructs capillary blood flow, disrupts metabolite clearance, and alters cell-to-cell

interactions. Specifically, volume overload has been shown to impair

pulmonary, cardiac, and renal function. A positive fluid balance is a

predictor of hospital mortality. As septic patients recover, volume excess

should be aggressively treated with the use of targeted diuretics and

renal replacement therapies if necessary.

T

he mainstay of treatment for sepsis is the early initiation of both antibiotic therapy and fl uid resuscitation (1). Recommendations based on the early

goal-directed therapy algorithm call for continued

administration of intravenous fluid until the central venous

pressure is at least 8 mm Hg (2) with the goal of maintaining

perfusion of vital organs. The underlying pathophysiologic

mechanism responsible for hypotension and hypoperfusion is

a combination of vasodilatation (leading to peripheral blood

pooling) and increased vascular permeability, which allows

fluid transfer from the vascular space to the interstitial fluid

compartment. The latter can result in large intravascular fluid

deficits. Bioimpedance vector analysis (BIVA) is a noninvasive technique that utilizes the principle that the body acts

as an electrical circuit with a measureable resistance and reactance. BIVA can be used to accurately quantify total body

water and is comparable to the gold standard of deuterium

dilution (r > 0.99) (3). BIVA has been used to identify volume overload in heart failure (4), liver disease (5), and renal

failure (6). We examined the incidence and degree of volume

overload in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU)

for sepsis syndromes.

12

METHODS

In this prospective observational study, BIVA was used to

measure total body water in patients admitted to the ICU for

the treatment of sepsis syndromes. Bioimpedance was measured

using an EFG Diagnostics CardioEFG machine. This device was

approved by TriMedx clinical engineering. The first measurement had to be obtained within 24 hours of ICU admission.

Serial measurements of total body water were taken until ICU

discharge or day 8, whichever occurred first.

We enrolled patients >18 years old who were admitted to

the ICU with the diagnosis of sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic

shock. Patients were classified as having sepsis, severe sepsis, or

septic shock based on the definitions set forth by the American

College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine

(7). We excluded patients with end-stage liver or kidney disease

(requiring dialysis). Data on demographic and clinical characteristics were collected prospectively. Excess total body water

(in L) was calculated by subtracting 74.3 (the upper limit of

normal) from the measured percent total body volume and

multiplying the difference by patient weight in kg. Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to

enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the St. John

Providence Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

A total of 18 patients were enrolled; 11 (61%) were men and

7 (39%) were women, and the mean age was 71 years (range,

43–93). Diabetes mellitus was present in 10 (56%) patients; hypertension, 14 (78%); heart failure, 4 (22%); liver disease, 1 (6%);

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Cardiology, Virginia Tech

Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia (Larsen); Department of Internal

Medicine, Providence Hospital and Medical Center, Southfield, Michigan (Singh,

Velocci, Nasser); and Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute, Baylor Jack and Jane

Hamilton Heart and Vascular Hospital and Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas,

Texas, and The Heart Hospital, Plano, Texas (McCullough).

Funding for this project was provided by the Providence Hospital and Medical

Center Research Committee.

Corresponding author: Timothy R. Larsen, DO, Department of Internal Medicine,

Section of Cardiology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, 2001 Crystal

Spring Avenue, Suite 203, Roanoke, VA 24014 (e-mail: tlarsen17@gmail.com).

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2016;29(1):12–15

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Age

(yrs)

1

Peak %

TBW

Mean daily

excess vol

(L)

Peak

excess

vol (L)

RH

84.9

6.5

8.0

Shock

RH

90.7

5.7

9.0

Shock

RF

96.9

9.1

11.4

31

Shock

RH

92.0

12.6

15.1

49

Shock

RH

92.9

17.7

26.2

4

37

Severe sepsis

RF

91.3

14.5

17.2

M

2

19

Shock

RH

91.8

10.9

11.1

M

4

30

Sepsis

Overdose

90.2

9.4

15.9

Gender

ICU LOS

(days)

BMI

(kg/m2)

Diagnosis

43

F

2

29

Severe sepsis

2

47

M

4

21

3

47

M

8

41

4

61

F

4

5

61

F

4

6

63

F

7

68

8

69

Patient

Reason for

ICU admit

9

69

F

5

26

Severe sepsis

RF

93.2

15.3

15.9

10

74

F

3

21

Severe sepsis

RF

91.4

7.5

8.2

11

75

M

1

22

Sepsis

Acidosis

81.2

5.0

5.0

12

81

M

3

25

Sepsis

RF

89.2

6.2

10.0

13

82

M

5

21

Severe sepsis

RH

82.5

1.4

5.6

14

82

F

2

19

Severe sepsis

RH

73.9

0

0

15

85

M

5

20

Shock

RH

93.1

10.1

11.3

16

85

M

6

19

Shock

RH

92.2

10.1

11.5

17

87

M

5

37

Shock

RF

94.0

21.3

23.4

18

93

M

3

21

Severe sepsis

RH

89.0

7.4

14.9

BMI indicates body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; RF, respiratory failure; RH, refractory hypotension; TBW, total body water; VOL, volume overload.

(r = 0.70, P = 0.001). On day 1, 10 (56%) had clinically evident

edema, and by day 3, all patients remaining in the ICU had

clinically evident edema. Twelve (67%) developed radiographic

evidence of pulmonary edema. Mean ICU stay was 3.8 days