Villanelle, Ballad, Sonnet: Poetry Forms Explained

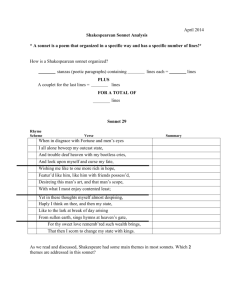

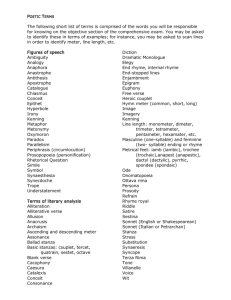

advertisement

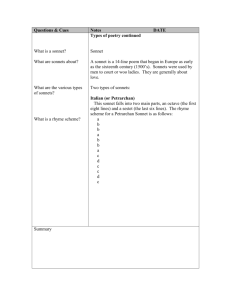

1. The Villanelle is a wonderfully challenging poetry form. It consists of ninteen lines which comprise of two rhymes that are very different in the way they are used. The unique thing about this form is that the first and third lines of the first verse become the alternating final lines of the next four verses. So the choice of the first and last line is very important and more so because in the last stanza they form a couplet and become the "Closure". If things weren't difficult enough already, all the 2nd lines of each stanza rhyme with each other. The Dylan Thomas Poem below is considered to be the finest example of this form and to help look at the rhyme patterns I've broken the lines into colour. Purple has been chosen for the first line and Red for third line of the first stanza. The first line of each follows the first stanza rhyme. Blue for the centre line rhyme. This line is probably the most important line in each stanza and the most difficult one to construct and I would recommend care in selecting your primary rhyme. Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night, Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night, Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Dylan Thomas Below are other examples of this form of poetry. See what you can make of them. One Art The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster, Lose something every day. Accept the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. The art of losing isn't hard to master. Then practice losing farther, losing faster: places, and names, and where it was you meant to travel. None of these will bring disaster. I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or next-to-last, of three loved houses went. The art of losing isn't hard to master. I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster. - Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident the art of losing's not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like a disaster. Elizabeth Bishop The Stalkers Villanelle unsaid. She flicks her hair, just as she would in bed When she'd make love as if it were a chore. She doesn't realize that she is dead. She doesn't realize that she is dead. Remembering the ring, the vows we swore, I follow her like something left unsaid. These strangers can't discern the life she's led. They see a charming smile; I see a whore And follow her like something left unsaid. She drives the car I gave her when we wed. She grips a steering wheel I've gripped before. She doesn't realize that she is dead. She surely feels her whole life lies ahead As she steps briskly through the exit door. She doesn't realize that she is dead. I follow her like something left unsaid. She's stepping from the car—her legs, her head! Watching her stroll into the grocery store, I follow her like something left Jeff Holt Reading Scheme Here is Peter. Here is Jane. They like fun. Jane has a big doll. Peter has a ball. Look, Jane, look! Look at the dog! See him run! Here is Mummy. She has baked a bun. Here is the milkman. He has come to call. Here is Peter. Here is Jane. They like fun. Go Peter! Go Jane! Come, milkman, come! The milkman likes Mummy. She likes them all. Look, Jane, look! Look at the dog! See him run! Here are the curtains. They shut out the sun. Let us peep! On tiptoe Jane! You are small! Here is Peter. Here is Jane. They like fun. I hear a car, Jane. The milkman looks glum. Here is Daddy in his car. Daddy is tall. Look, Jane, look! Look at the dog! See him run! Daddy looks very cross. Has he a gun? Up milkman! Up milkman! Over the wall! Here is Peter. Here is Jane. They like fun. Look, Jane, look! Look at the dog! See him run! Wendy Cope THE BALLAD Centuries-old in practice, the composition of ballads began in the European folk tradition, in many cases accompanied by musical instruments. Ballads were not originally transcribed, but rather preserved orally for generations, passed along through recitation. Their subject matter dealt with religious themes, love, tragedy, domestic crimes, and sometimes even political propaganda. A typical ballad is a plot-driven song, with one or more characters hurriedly unfurling events leading to a dramatic conclusion. At best, a ballad does not tell the reader what’s happening, but rather shows the reader what’s happening, describing each crucial moment in the trail of events. To convey that sense of emotional urgency, the ballad is often constructed in quatrain stanzas, each line containing as few as three or four stresses and rhyming either the second and fourth lines, or all alternating lines. Ballads began to make their way into print in fifteenth-century England. During the Renaissance, making and selling ballad broadsides became a popular practice, though these songs rarely earned the respect of artists because their authors, called "pot poets," often dwelled among the lower classes. However, the form evolved into a writer’s sport. Nineteenth-century poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworthwrote numerous ballads. Coleridge’s "Rime of the Ancient Mariner," the tale of a cursed sailor aboard a storm-tossed ship, is one of the English language’s most revered ballads. Other balladeers, including Thomas Percy and, later, W. B. Yeats, contributed to the English tradition. In America, the ballad evolved into folk songs such as "Casey Jones," the cowboy favorite "Streets of Laredo," and "John Henry." THE SONNET From the Italian sonetto, which means "a little sound or song," the sonnet is a popular classical form that has compelled poets for centuries. Traditionally, the sonnet is a fourteen-line poem written in iambic pentameter, which employ one of several rhyme schemes and adhere to a tightly structured thematic organization. Two sonnet forms provide the models from which all other sonnets are formed: the Petrachan and the Shakespearean. Petrarchan Sonnet The first and most common sonnet is the Petrarchan, or Italian. Named after one of its greatest practitioners, the Italian poet Petrarch, the Petrarchan sonnet is divided into two stanzas, the octave (the first eight lines) followed by the answering sestet (the final six lines). The tightly woven rhyme scheme, abba, abba, cdecde or cdcdcd, is suited for the rhyme-rich Italian language, though there are many fine examples in English. Since the Petrarchan presents an argument, observation, question, or some other answerable charge in the octave, a turn, or volta, occurs between the eighth and ninth lines. This turn marks a shift in the direction of the foregoing argument or narrative, turning the sestet into the vehicle for the counterargument, clarification, or whatever answer the octave demands. Sir Thomas Wyatt introduced the Petrarchan sonnet to England in the early sixteenth century. His famed translations of Petrarch’s sonnets, as well as his own sonnets, drew fast attention to the form. Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, a contemporary of Wyatt’s, whose own translations of Petrarch are considered more faithful to the original though less fine to the ear, modified the Petrarchan, thus establishing the structure that became known as the Shakespearean sonnet. This structure has been noted to lend itself much better to the comparatively rhyme-poor English language. Shakespearean Sonnet The second major type of sonnet, the Shakespearean, or English sonnet, follows a different set of rules. Here, three quatrains and a couplet follow this rhyme scheme: abab, cdcd, efef, gg. The couplet plays a pivotal role, usually arriving in the form of a conclusion, amplification, or even refutation of the previous three stanzas, often creating an epiphanic quality to the end. In Sonnet 130 of William Shakespeare’s epic sonnet cycle, the first twelve lines compare the speaker’s mistress unfavorably with nature’s beauties. But the concluding couplet swerves in a surprising direction: My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress when she walks treads on the ground. And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare. Sonnet Variations Though Shakespeare’s sonnets were perhaps the finest examples of the English sonnet, John Milton’s Italian-patterned sonnets (later known as "Miltonic" sonnets) added several important refinements to the form. Milton freed the sonnet from its typical incarnation in a sequence of sonnets, writing the occasional sonnet that often expressed interior, self-directed concerns. He also took liberties with the turn, allowing the octave to run into the sestet as needed. Both of these qualities can be seen in "When I Consider How my Light is Spent." The Spenserian sonnet, invented by sixteenth century English poet Edmund Spenser, cribs its structure from the Shakespearean--three quatrains and a couplet--but employs a series of "couplet links" between quatrains, as revealed in the rhyme scheme: abab, bcbc, cdcd, ee. The Spenserian sonnet, through the interweaving of the quatrains, implicitly reorganized the Shakespearean sonnet into couplets, reminiscent of the Petrarchan. One reason was to reduce the often excessive final couplet of the Shakespearean sonnet, putting less pressure on it to resolve the foregoing argument, observation, or question. Sonnet Sequences There are several types of sonnet groupings, including the sonnet sequence, which is a series of linked sonnets dealing with a unified subject. Examples include Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese and Lady Mary Roth’s The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, published in 1621, the first sonnet sequence by an English woman. Within the sonnet sequence, several formal constraints have been employed by various poets, including the corona (crown) and sonnet redoublé. In the corona, the last line of the initial sonnet acts as the first line of the next, and the ultimate sonnet’s final line repeats the first line of the initial sonnet. La Corona by John Donne is comprised of seven sonnets structured this way. The sonnet redoublé is formed of 15 sonnets, the first 14 forming a perfect corona, followed by the final sonnet, which is comprised of the 14 linking lines in order. Modern Sonnets The sonnet has continued to engage the modern poet, many of whom also took up the sonnet sequence, notably Rainer Maria Rilke, Robert Lowell, and John Berryman. Stretched and teased formally and thematically, today’s sonnet can often only be identified by the ghost imprint that haunts it, recognizable by the presence of 14 lines or even by name only. Recent practitioners of this so-called “American” sonnet include Gerald Stern, Wanda Coleman, Ted Berrigan, and Karen Volkman. Hundreds of modern sonnets, as well as those representing the long history of the form, are collected in the recent anthology The Penguin Book of the Sonnet: 500 Years of a Classic Tradition in English, edited by Philis Levin. TERZA RIMA Invented by the Italian poet Dante Alighieri in the late thirteenth century to structure his three-part epic poem, The Divine Comedy, terza rima is composed of tercets woven into a rhyme scheme that requires the end-word of the second line in one tercet to supply the rhyme for the first and third lines in the following tercet. Thus, the rhyme scheme (aba, bcb, cdc, ded) continues through to the final stanza or line. Dante chose to end each canto of the The Divine Comedy with a single line that completes the rhyme scheme with the end-word of the second line of the preceding tercet. Terza rima is typically written in an iambic line, and in English, most often in iambic pentameter. If another line length is chosen, such as tetrameter, the lines should be of the same length. There are no limits to the number of lines a poem composed in terza rima may have. Possibly developed from the tercets found in the verses of Provencal troubadours, who were greatly admired by Dante, the tripartite stanza likely symbolizes the Holy Trinity. Early enthusiasts of terza rima, including Italian poets Boccaccio and Petrarch, were particularly interested in the unifying effects of the form Fourteenth-century English poet Geoffrey Chaucer introduced terza rima to England with his poem "Complaints to his Lady," while Thomas Wyatt is credited, with popularizing its use in the English language through his translations and original works. Later, the English Romantic poets experimented with the form, including Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose "Ode to the West Wind" is an example of what is sometimes called "terza rima sonnet," in which the final stanza comes in couplet form. A clever mixture of poetic techniques, the poem is a series of five terza rima sonnets, of which the following is the first: 0 wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being, Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing, Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red, Pestilence-stricken multitudes: 0 thou, Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed The wingèd seeds, where they lie cold and low, Each like a corpse within its grave, until Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow Her clarion o'er the dreaming earth, and fill (Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air) With living hues and odours plain and hill: Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere; Destroyer and Preserver; hear, 0 hear! Twentieth-century examples of terza rima come in two different forms: poets who have written in the form and scholars and poets who have translated Dante. Those who have written in terza rima usually employ near and slant rhymes, as the English language, though syntactically quite versatile, is rhyme poor. "The Yachts" by William Carlos Williams and "Acquainted with the Night" by Robert Frost are two examples. More recent works written in terza rima include "The Sow" by Sylvia Plath and the eponymous "Terza Rima" by Adrienne Rich. While there are nearly as many translations of Dante as there are cantos in his masterpiece, the question of how to reproduce the intricate rhyme scheme of terza rima—namely, the reproduction of the rich rhyming possibilities offered by the Italian language—has been a principle concern for translators. John Ciardi chose not to concern his translation with a faithful rendering of the terza rima rhyme scheme; he thought such a gesture would be a "disaster." Robert Pinsky chose a different approach in his translation of the Inferno, employing a terza rima that rhymed when possible, and used near and slant rhymes in places where the rhyme might seem forced, creating what he called "a plausible terza rima in a readable English." Acquainted with the Night I have been one acquainted with the night. I have walked out in rain -- and back in rain. I have outwalked the furthest city light. I have looked down the saddest city lane. I have passed by the watchman on his beat And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet When far away an interrupted cry Came over houses from another street, But not to call me back or say good-bye; And further still at an unearthly height, A luminary clock against the sky Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right. I have been one acquainted with the night. Robert Frost THE TRIOLET The triolet is a short poem of eight lines with only two rhymes used throughout. The requirements of this fixed form are straightforward: the first line is repeated in the fourth and seventh lines; the second line is repeated in the final line; and only the first two end-words are used to complete the tight rhyme scheme. Thus, the poet writes only five original lines, giving the triolet a deceptively simple appearance: ABaAabAB, where capital letters indicate repeated lines. French in origin, and likely dating to the thirteenth century, the triolet is a close cousin of the rondeau, another French verse form emphasizing repetition and rhyme. The earliest triolets were devotionals written by Patrick Carey, a seventeenth-century Benedictine monk. British poet Robert Bridges reintroduced the triolet to the English language, where it enjoyed a brief popularity among late-nineteenth-century British poets. Though some employed the triolet as a vehicle for light or humorous themes, Thomas Hardy recognized the possibilities for melancholy and seriousness, if the repetition could be skillfully employed to mark a shift in the meaning of repeated lines. In "How Great My Grief," Hardy displays both his mastery of the triolet and the potency of the form: How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee! - Have the slow years not brought to view How great my grief, my joys how few, Nor memory shaped old times anew, Nor loving-kindness helped to show thee How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee? The first line, "How great my grief, my joys how few," is, in its two subsequent appearances, modified by the movement of time in the poem. Initially, the line assumes a declarative position, indicating the subject and tone of the poem, one of grief and love lost. By its third iteration, after several queries to the person being addressed, the line takes on the added weight of the speaker’s astonished grief that the addressee has not, despite the years, recognized the speaker’s profound sense of loss. Triolet I used to think all poets were Byronic-Mad, bad and dangerous to know. And then I met a few. Yes it's ironic-I used to think all poets were Byronic. They're mostly wicked as a ginless tonic And wild as pension plans. Not long ago I used to think all poets were Byronic-Mad, bad and dangerous to know. Wendy Cope THE ODE "Ode" comes from the Greek aeidein, meaning to sing or chant, and belongs to the long and varied tradition of lyric poetry. Originally accompanied by music and dance, and later reserved by the Romantic poets to convey their strongest sentiments, the ode can be generalized as a formal address to an event, a person, or a thing not present. There are three typical types of odes: the Pindaric, Horatian, and Irregular. The Pindaric is named for the ancient Greek poet Pindar, who is credited with inventing the ode. Pindaric odes were performed with a chorus and dancers, and often composed to celebrate athletic victories. They contain a formal opening, or strophe, of complex metrical structure, followed by an antistrophe, which mirrors the opening, and an epode, the final closing section of a different length and composed with a different metrical structure. The William Wordsworth poem "Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood" is a very good example of an English language Pindaric ode. It begins: There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, The earth, and every common sight To me did seem Apparelled in celestial light, The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;-Turn wheresoe'er I may, By night or day, The things which I have seen I now can see no more. The Horatian ode, named for the Roman poet Horace, is generally more tranquil and contemplative than the Pindaric ode. Less formal, less ceremonious, and better suited to quiet reading than theatrical production, the Horatian ode typically uses a regular, recurrent stanza pattern. An example is the Allen Tate poem "Ode to the Confederate Dead," excerpted here: Row after row with strict impunity The headstones yield their names to the element, The wind whirrs without recollection; In the riven troughs the splayed leaves Pile up, of nature the casual sacrament To the seasonal eternity of death; Then driven by the fierce scrutiny Of heaven to their election in the vast breath, They sough the rumour of mortality. The Irregular ode has employed all manner of formal possibilities, while often retaining the tone and thematic elements of the classical ode. For example, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" by John Keats was written based on his experiments with the sonnet. Other well-known odes include Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ode to the West Wind," Robert Creeley's "America,"Bernadette Mayer's "Ode on Periods," and Robert Lowell's"Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket." Here is one example of the form you might be able to appreciate: To Sleep BY JOHN KEATS O soft embalmer of the still midnight, Shutting, with careful fingers and benign, Our gloom-pleas'd eyes, embower'd from the light, Enshaded in forgetfulness divine: O soothest Sleep! if so it please thee, close In midst of this thine hymn my willing eyes, Or wait the "Amen," ere thy poppy throws Around my bed its lulling charities. Then save me, or the passed day will shine Upon my pillow, breeding many woes,— Save me from curious Conscience, that still lords Its strength for darkness, burrowing like a mole; Turn the key deftly in the oiled wards, And seal the hushed Casket of my Soul. BLANK VERSE Blank verse is poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the sixteenth century" and Paul Fussell has claimed that "about three-quarters of all English poetry is in blank verse." LYRIC POETRY A short poem with one speaker (not necessarily the poet) who expresses thought and feeling. Though it is sometimes used only for a brief poem about feeling (like the sonnet).it is more often applied to a poem expressing the complex evolution of thoughts and feeling, such as the elegy, the dramatic monologue, and the ode. The emotion is or seems personal In classical Greece, the lyric was a poem written to be sung, accompanied by a lyre. Lyric poetry makes its impact in a very brief space. It stresses moments of feeling. It is often quite memorable. In these and several other ways, lyric poems resemble two other kinds of "texts" with which we are quite familiar: ninety-second popular songs and fifteen-second television commercials. Both of these aim, in extremely brief time, to capture moments of feeling. Both aim to imprint themselves in our memory. To achieve this, besides repeated air play, both use internal forms of repetition. DRAMATIC MONOLOGUE Dramatic monologue in poetry, also known as a persona poem, shares many characteristics with a theatrical monologue: an audience is implied; there is no dialogue; and the poet speaks through an assumed voice—a character, a fictional identity, or a persona. Because a dramatic monologue is by definition one person’s speech, it is offered without overt analysis or commentary, placing emphasis on subjective qualities that are left to the audience to interpret. Though the technique is evident in many ancient Greek dramas, the dramatic monologue as a poetic form achieved its first era of distinction in the work of Victorian poet Robert Browning. Browning’s poems "My Last Duchess" and "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister," though considered largely inscrutable by Victorian readers, have become models of the form. His monologues combine the elements of the speaker and the audience so deftly that the reader seems to have some control over how much the speaker will divulge in his monologue. This complex relationship is evident in the following excerpt from "My Last Duchess": Even had you skill In speech—(which I have not)—to make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say, 'Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark' -- and if she let Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse, —E'en then would be some stooping... In the twentieth century, the influence of Browning’s monologues can be seen in the work of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot. In Eliot’s "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," readers find the voice of the poet cloaked in a mask, a technique that Eliot mastered in his career. More recently, a number of poets have offered variations on the form, including "Mirror" and"Lady Lazarus" by Sylvia Plath, and "Daffy Duck in Hollywood"by John Ashbery. John Berryman used the form in his series ofDream Songs, writing poems with shifting narrators, including his alter egos "Henry" and "Mr. Bones." One powerful example of the interplay between a dramatic monologue and the perception of the audience is "Night, Death, Mississippi," by Robert Hayden. In the poem, Hayden adopts the shocking persona of an aging Klan member, listening longingly to the sounds of a lynching outside, but too feeble to join. He says to himself: Christ, it was better than hunting bear which don’t know why you want him dead. The effect of reading the casual violence of the poem is more devastating than any commentary the poet could have provided. Hayden wrote many other dramatic monologue poems, including several dramatizing African American historical figures such as Phillis Wheatley and Nat Turner, as well as inventive characters such as the alien voice reporting his observations in "American Journal." Though not written in the first person, James Dickey's long poem "Falling" is inspired by a true story, and offers the impossible narrative of a stewardess who is accidentally blown from a plane and falls helplessly to the ground. The poem is voiced by an omniscient speaker who seems to fly invisibly beside her, observing her calm descent, her twists and tumbles, listening as she imagines herself as a goddess looking for water to dive into, and then finally watching as she removes her clothes, unsnapping her bra and sliding out of her girdle, before finally coming to rest in a Kansas field. Dickey transforms this terrifying reality into sensual transcendence, as he writes: "Her last superhuman act the last slow careful passing of her hands / All over her unharmed body desired by every sleeper in his dream." NARRATIVE POEMS Narrative poetry is a form of poetry which tells a story, often making use of the voices of a narrator and characters as well; the entire story is usually written in metered verse. The poems that make up this genre may be short or long, and the story it relates to may be complex. It is usually dramatic, with objectives, diverse characters, and meter. Narrative poems include epics, ballads, idylls and lays.