Managing Design as a Core Competency

advertisement

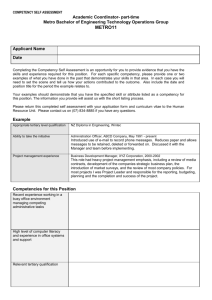

DESIGN MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE Design Management Review Vol. 20 No. 2, Spring 2009 Article Reprint Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea Brigitte Borja de Mozota, Parsons Paris School of Art and Design Bo Young Kim, Seoul School of Integrated Sciences and Technologies Design Management Institute 101 Tremont Street, Suite 300 Boston, MA 02108 USA www.dmi.org © Spring 2009 by the Design Management InstituteNo part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission. S T R AT E G Y The companies profiled here have built their success on a new understanding of design, exploiting it as a dynamic, proactive resource that leverages knowledge and research, human capital, culture, and technology. Brigitte Borja de Mozota, Director of Research, Parsons Paris School of Art and Design Bo Young Kim, Assistant Professor, Seoul School of Integrated Sciences and Technologies Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea by Brigitte Borja de Mozota and Bo Young Kim The new IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) adopted by the International Accounting Standards Board to measure corporate “intangibles” have created a new valuation framework for companies and a unique opportunity for the design profession and design managers. The intangibles to be measured under IFRS include technology, customer relationship, brand, and human capital. Design reaches into all of these. 1 Indeed, IFRS will mean that design managers must understand design as an intangible asset for their organizations. 1. http://www.iasb.org/home.htm. Previous research has already demonstrated that there are two ways to build a company’s competitive advantage through design. One way is through design as an external competitive advantage, built on Porter’s value chain model—that is, strategy as “fit” (with the external environment or market). This view of design is reactive—the vision of the company’s potential with regard to its competitive environment. Consequently, it is a passive vision of design’s strategic value. The other way is to consider design as a core competency or as a sustainable competitive advantage. This approach built on another theo- retical framework of strategy—the resource-based view (RBV). Our objective in this article is to explain the RBV of design management using case studies of seven Korean companies, defining the tools and methods for the learning curve from design strategy as fit to design strategy as core competency. A little background The history of design management can be summarized by five phases (Figure 1 on next page). Since 2000, most design-oriented companies have transformed their view from design as differentiation value to design as 67 Design as I ntegral to Business Success transformation value. The strength of this strategy emerges as companies think of design processes as not only project management tools but also as organizational capabilities that repeatedly provide superior customer care. Design is now understood as an activity, a profession, or a creative industry that has a specific body of knowledge and is based on research. However, until now, most design management programs in design schools and design agencies have followed the vision of corporate strategy as fit, and refer to strategic tools such as SWOT analysis and the value chain model, thus interpreting design management as project management. Of course, management at many firms believe that designers’ skills help in selecting a company’s strategic positioning through brand differentiation and product strategy. But this might actually hurt the design profession, because design strategy as fit tends to limit the understanding of design knowledge to one involving pretty artifacts and emotional value. Such firms do not manage design as a capability and a process interwoven with process management, decision management, and knowledge management. The resource-based view offers another path for design strategy, one that is better for designers. It requires a proactive decision to understand design knowledge in the company as a strategic choice, and to understand that selecting design as a core competency is a strength. Resourcebased management highlights how the possession of valuable, rare, and inimitable resources may result in sustained superior performance. The RBV of a firm’s competitive advantage emphasizes the importance of the invisible assets—the value of “design you can’t see.” oped by Wernerfelt in 1984, and was elaborated by Helfat and Peteraf in 2003.2 A resource refers to an asset or input to production (tangible or intangible) that an organization owns, controls, or has access to on a semi-permanent basis. Prahalad and Hamel3 argue that informationbased invisible assets, such as technology, customer trust, brand image, corporate culture, and management skills, are the real resources of competitive advantage, because they are difficult and time-consuming to accumulate and difficult to imitate, and they can be used in multiple ways simultaneously. For design managers, the RBV means valuing design skills as rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable— and this is in addition to the value of design outputs. Rare is the company Strategic design or design capabilities as a resource 2. Helfat, C.E., and M.A. Peteraf, “The Dynamic Resource-Based View: Capability Lifecycles,” Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 2003, pp. 997-1010. 3. Prahalad, C.K., and G. Hamel, The Core Competence of the Corporation (Heidelberg: Springer Berlin, 1990). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage was first devel- Figure 1. Historical Development of Design Management 68 Period Main Perspective Design Role Design Management Focus Cases 1940s to1950s Design as function Product quality None AEG, Olivetti 1960s to1970s Design as style Quality communication Project management Alessi, Braun 1980s to1990s Design as process Innovation NPD Innovation management Philips, Sony 1990s to 2000s Design as leadership Creativity strategy Brand Apple 2000s to now Design thinking New business model Creative organization IDEO Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea that can claim both, because to do so requires coherence with the firm’s strategy leadership and culture, which points toward a long-term perspective and the building of a sustainable competitive advantage. Within such a strategic long-term vision, design management can be used as an efficient trigger by capitalizing on new knowledge after each design project, and by taking a process view to change management’s view of design management (Figure 2). Design managers, designers, and design educators, when pleading for strategic design, should think about how they define strategy. Is it strategy as fit, or strategy as RBV? As we see now, design management has been moving from considering design as an external competitive advantage (fit with the external environment) to also thinking of design as an internal, sustained competitive advantage (a resource or a core competency). Design valuation has transitioned from an economic view (increasing market share and brand) to a process performance view (reducing cost or time to market and improving innovation systems) to a strategic view of resources (creating new markets and retaining valued employees). Figure 3 visualizes this shift, as well as the learning curve of design often referred to as the design ladder. It also explains the importance of the Figure 2. The resource-based view of a firm. (Adapted from John Fahy, The Role of Resources in Global Competition, Routledge Publishers, 2000.) Figure 3. From design as fit to design as resource. Design as human capital: Human capital refers to the talents of designers as individuals and in design groups. This core competency also values design as a way of improving talent and creativity in the workforce and fostering the recruitment of talent in other functions. Design as knowledge capital: Design as knowledge capital involves research and research tools, design ideas, and design thinking. Design management is linked with knowledge management. Design as cultural capital: The cultural capital of design involves the internalization of design culture within the organization. To improve design culture, companies often use design awards, informal meetings, events, or communications networks. Cultural capital also grows from building unique brand value and customer relationships. Design as technology capital: Design technology capital includes research skills, the technical skills used in prototyping and advanced design technologies such as CAD, along with rendering, and programming that are embedded in the organization’s technology and computer information systems management. Skills used in developing patents and intellectual property through technology are another aspect of this kind of capital. 69 Design as I ntegral to Business Success intermediary and tactical decision level of design management as process performance. Design as competitive advantage is often easily understood because of its tangible and measurable outputs. Design as core competency is more difficult to understand for someone who is not used to thinking of design as a profession or as a body of knowledge (see Figure 4). However, the current trend toward blue ocean strategy (creating new market space rather than competing in an existing industry) and of creating innovation through sustainable change have offered examples of the importance of unique internal core competencies— such as design—as a way of building competitive advantage. Unlike managing design as competitive advantage, managing it as a core competency is high-risk, because the ROI is not immediate in sales. This is the reason that many companies have been reluctant to invest in building design capabilities. How- Figure 4. What Do We Mean by Design as Core Competency? Design as Competitive Advantage Design as Core Competency Design t1SPEVDUBOECSBOEEJõFSFOUJBUJPO t*OUFSOBMTLJMMTQSPDFTTBOELOPXMFEHF Design Management t$FOUSBMJ[FEEFTJHONBOBHFNFOU t%SJWFOCZMBSHFQSPEVDUDPNQBOJFT t%FTJHOHPWFSOBODFCZ$&0 t*NQMFNFOUJOHBEFTJHONBOBHFNFOUTZTUFN t*NQSPWJOHUIFEFTJHOMFEQSPDFTT t%FTJHOHPWFSOBODFCZDIJFGEFTJHOPöDFSPSDSFBUJWFEJSFDUPS Main Issues t#VJMEJOHUBOHJCMFEFTJHOMFBEFSTIJQ t%FWFMPQJOOPWBUJPOCZEFTJHO t%FTJHODMPTFUPCSBOEJOHPSUP3% t%FTJHOTUSBUFHZUFBNGPSBDSFBUJWFPSHBOJ[BUJPO t%FWFMPQJOHEFTJHOBUCPBSEMFWFM t#VJMEJOHEFTJHOBTBOJOUBOHJCMFWBMVF t%FTJHOBTJOEFQFOEFOUGVODUJPO Figure 5. Enhancing the Value of the Intangibles Through Design Management Amore Pacific Human Capital Knowledge Capital Cultural Capital t%FTJHOPOMJOFFEVDBUJPO t%FTJHO*OOPWBUJPO'PSVN t'VO$PNNVOJUZ t#VJMEJOHHMPCBMEFTJHO information infrastructure t%FTJHOTDJFODF improvement t*NQSPWJOHQSPEVDU identity t*OOPWBUJPOPGEFTJHO development process Hankook Tire 70 Technology Capital Winia Mando t4VQQPSUJOHEFWFMPQNFOU of designer’s skill and knowledge t$VTUPNFSNPOJUPSJOH t%JTDPWFSJOHOFXOFFET t%FWFMPQJOHDSFBUJWF design thinking and idea t$VMUVSBMMJGFTUZMFEFTJHO t'VUVSFEFTJHO KTF t5PUBMEFTJHOFEVDBUJPO t%FTJHOGSPOUJFS t%FTJHOSFTFBSDI t%FTJHOQSPUFDUJOHTZTUFN t0SBOHF%SFBN5FBN (design support team) t%FTJHODPOTVMUJOHQSPHSBN Daewoo Electronics t%FTJHORVBMJUZDPOUSPM group (mentoring) t(MPCBMOFUXPSLSFTFBSDI LG Electronics t4VQFSEFTJHOFSQSPHSBN t*ODFOUJWFTZTUFN t%JõFSFOUUIJOLJOH benchmarking t%FTJHOmSTUTZTUFN t%FTJHOMFEDSPTTGVODUJPOBM team Samsung Electronics t3FDSVJUBOETFDVSFUIF world’s best designers t*NQSPWJOHEFTJHO intelligence t$SFBUJOHSFNBSLBCMF designs t%FTJHOFEVDBUJPOUP general employees t/VSUVSJOHBDSFBUJWF corporate environment t3FJOGPSDJOHUFDIOPMPHZ infrastructure t"DBEFNJDJOEVTUSJBM cooperation t%oDBNQEFTJHOXPSLTIPQ Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea ever, adopting a long-term resource view of design management improves the probability of achieving success in change management in the present chaotic business environment. Korean companies are notoriously in favor of design-driven management because they believe that corporate design capability is a key competency in the Korean market, which is particularly sensitive to new design trends. We present seven companies— Amore Pacific, Hankook Tire, Winia Mando, KTF, Daewoo Electronics, LG Electronics, and Samsung Electronics—all winners of the Korea Institute of Design Promotion’s Design Management Award. They were selected for our case studies because they have all made the transition from design as fit to design as core competency. Each of these companies tends to develop specific skills according to its design management objective (Figure 5 on previous page). Consider Amore Pacific, a health and beauty company specializing in skin care (Figure 6). In the past, Amore had not been interested in product or packaging design; its focus was entirely on developing new cosmetics. That attitude changed after the huge success of one of its products, the Laneige sliding pact—which essentially found success because of its packaging design. Figure 6. Amore Pacific beauty products (left: Laneige’s sliding pact; right: Lolita Lempicka perfume). Now the firm invests in improving its design-led product development process, as well as in developing its design culture and thinking. Hankook Tire concentrates on service and promotional design skills in its drive to improve customer service and brand equity (Figure 7). In the past, the company saw no need to interest itself in design, believing that as an industrial firm, its product needed design only to improve its product patterns. Upon reflection, however, Hankook considered that design promotion might be an effective way to improve its relationship with customers. One of Hankook’s internal designers suggested a tire design contest, which proved to be a great success, and now the firm is more open to using design thinking to promote its brand, improve its culture, and branch out into new markets across the globe. KTF has achieved steady growth by communicating emotion and creative positive experiences. The company’s design services have created a unique customer support system Figure 7. Hankook Tire: a focus on strategic innovative design (left, the Ventura V12 tire; right, corporate advertising). 71 Design as I ntegral to Business Success for its subscribers, allowing KTF to improve customer service and launch proactive marketing activities, thus improving satisfaction rates. KTF is trying to develop its design resources toward establishing new services and making design part of its culture and business. 4 Winia Mando, a manufacturer of industrial machinery, has adopted a long-term strategy of developing skills in design thinking and design trends in order to create future markets—reinventing, for instance, the traditional food refrigerator based on a designled product development process. Daewoo Electronics (Figure 8) emphasizes customer-centered design and design research skills. Nine years ago, Daewoo changed its management philosophy and began to use the company’s design resources to research customer behavior and to meet the needs they discovered with fresh ideas and pleasing designs. Design management at LG Electronics focuses on future leadership through design research and trend development. In 2000, LG’s design center built internal research teams around mobile communications, digital appliances, digital displays, home networks, material and multimedia processing technologies, and 4. See “Designed by KTF: A Telecoms Case Study,” in the Winter 2008 Design Management Review for more details. 72 network home solutions (Figure 9 on previous page). In the past, the company’s design center focused only on developing design styling and rendering. Now, however, owever,, it concentrates on improving its design and design-related research skills. Samsung Electronics (Figure 10 on next page) is a design-driven company with worldwide ambitions. Its design aims concentrate primarily on creating new business and new markets. In 2005, Samsung’s global design center announced a Second Design Revolution and its hope that it would lead, not follow, global design trends. If design is to be thought of as a resource rather than as an external competitive advantage, design management leadership will entail enhancing the value of the company’s intangibles by improving the value of its human capital, knowledge capi- Figure 8. Products from Daewoo Electronics (left: Klasse kimchi refrigerator; right: Klasse refrigerator). Figure 9. LG Electronics’s design management focuses on future leadership through design research and trend development. This is the LG HS33S, an iPod-friendly home theater system. Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea tal, cultural capital, and technology capital (Figure 11). All seven of our companies are now functioning on an RBV level. Human capital: Educating, motivating, and recruiting Designers and design groups are a company’s human capital. They must be supported with further education and skill development, which foster motivation and help to recruit other team members. For example, Amore Pacific’s design management strategy focuses on knowledge-based communities—forums and seminars, for example—to enhance design thinking within the corporation. Both Figure 10. Samsung’s ZIPEL electronic products for the kitchen. Amore and telecommunications provider KTF (Figure 12 on next page) encourage their designers to attend business, marketing, and language courses. Winia Mando also supports its designers’ skills and knowledge development through its coaching program and mentoring system. Daewoo and LG have both focused on motivating designers through mentoring and incentive systems. Samsung tries to recruit the best designers available in order to improve its internal human capital. The problem with the educational programs we have studied in our sample is that they are often limited to questions around developing innovative new products rather than on improving the skills and creativity of the designers. Designers Figure 11. A model for managing design as a core competency. 73 Design as I ntegral to Business Success Figure 12. Telecommunications company KTF (top: a typical store; bottom: promotional products). 74 Managing Design as a Core Competency: Lessons from Korea and design teams need more designspecific educational opportunities. Knowledge capital: Improving the quality of research work and design thinking All our sample companies share the belief that design knowledge capital is the competency most important to their business success. Most of them offer workshops in design thinking and support seminars and other programs aimed at improving design research and development. To enhance their efforts, most of our seven companies have developed design research systems or programs. In large part, they concentrate on data collection schemes and design knowledge networks and on finding ways to integrate them into the company. Amore and LG focus on improving creative design thinking through regular workshops, seminars, and trips abroad to explore other cultures. Winia Mando, KTF, and Daewoo have improved design research skills based on new market and customer research projects. One of Winia’s design management strategies is to enhance the company’s design network through connections with other Korean designers and design professionals. Winia encourages its designers to attend design festivals, exhibitions, and other social events. The company believes this informal network will cross-fertilize its designers with new ideas, and will turn up good outsourcing partners, as well. Cultural capital: Sharing design mind and information Our case companies run special programs to improve the understanding of design processes and thinking throughout the organization. Amore, for instance, has its Fun Community, a design-based workshop meant to develop the creative and emotional minds of its employees, who are thus able to closely communicate with designers. Samsung Electronics believes that nondesign team members must be well-educated in design knowledge and process; the company runs design education programs for engineers, as well as for marketers. Daewoo Electronics also manages programs to enhance the design ideation process. Winia and LG are building designled processes and systems to improve their design competencies. KTF’s design support team, the Orange Dream Team (orange being KTF’s signature brand color), aims to increase design communication and design thinking within internal groups. The team rotates frequently in order to provide design information and knowledge to the wider organization. Technology capital: Developing design process and collaboration In order to develop design skills and technologies, our case companies work with external research groups with new ideas and innovative technologies. Winia concentrates on creating designs for cultural lifestyles. Its main research partner, Kodas (a design firm), sends its researchers all over the world to report on global design trends and to return with information from which Winia gleans ideas for new products. LG is also building design-led processes within the design center, focusing especially on design motivation with training programs and incentive systems. Samsung is reinforcing its design technologies with new mock-up and mold tools. KTF networks with professional experts and is providing design support programs to build design-centered processes. For its part, Daewoo manages a regular design workshop and a D-camp; it also collaborates with academic research centers. Conclusion Many companies are going through a learning curve that leads from an economic view of design to a more strategic and resource-based view. The danger is that in adopting this view of design, companies may miss its relevance at a managerial and tactical- 75 Design as I ntegral to Business Success process level. The design-driven companies lionized in the design management community, in contrast, understand design as a resource and a way in which to build sustainable competitive advantage. In such companies, the scope of design management is broader and more processdriven than it would be if it were used on a project-by-project basis. Our seven Korean companies exemplify the shift from a project-based view to a process-and-knowledge view. Returning to the discussion of the new IFRS norms with which we began, we must consider that there is a strategic correlation between the resource-based view of design and the value of corporations from the perspective of finance and auditors, stock markets, and national competitive advantage. How many design educators and design directors are aware of the new IFRSs norms for evaluation and the fantastic opportunities they represent for the design profession? Adopting a resource-based view of strategic design will be fundamental to linking design management to the new IFRS norms of international accounting. Design managers should turn their focus toward rewriting 76 their design strategy to reflect the resource-based view and the longterm evaluation system of IFRS and intangibles. Suggested Reading Borja de Mozota, Brigitte. Design Management: Using Design to Build Brand Value and Corporate Innovation (New York: Allworth Press, 2003). Borja de Mozota, Brigitte. “Design and Competitive Edge: A Model for Design Management Excellence in European SMEs.” Design Management Journal, 2002, pp. 88-104. Foss, Nicolai J. Resources, Firms, and Strategies: A Reader in the ResourceBased Perspective (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998). Lee, J. W., and B. Y. Kim, Design Marketing (Korea: 21Century Press, 2007). Lee, W. S., and B. Y. Kim, “Designed by KTF: A Telecoms Case Study.” Design Management Review, vol. 19, no. 1 (Winter 2008). Porter, Michael E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Free Press, 1998). Acknowledgment Our special thanks to design manager Ho-Kyung Oh in Hankook Tire’s design team, to design director Hee-In Shin in Winia Mando’s design department, to Ji-Youn Lee at LG Electronics Design Centre, to design manager Hyun-Sun Shin at Amore Pacific, to Professor Sung-Wook Hwang in Seoul Digital University, and to everyone who supported this paper. Reprint #09202MOZ66