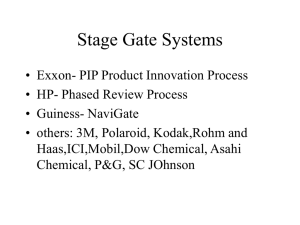

The Stage-Gate Idea-to-Launch Process

advertisement