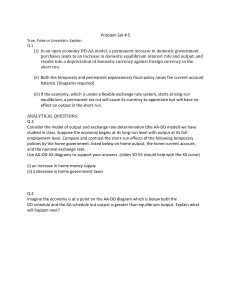

Concepts of equilibrium exchange rates

advertisement