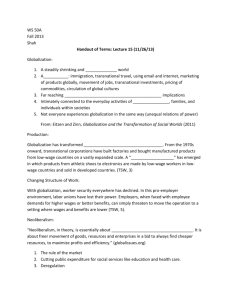

The Sources of Neoliberal Globalization

advertisement