Integrating Compliance-based and Commitment

Integrating Compliance-based and

Commitment-based Approaches in

Corporate Sustainability Management

Catherine A. Ramus and Karin Oppegaard

IMD 2007-04

Catherine A. Ramus

Visiting Faculty

IMD International

Chemin de Bellerive 23

1001 Lausanne

Switzerland

E-mail: cathie.ramus@imd.ch

Tel: +41 21 618 0559

Fax: +41 21 618 0707 and

Karin Oppegaard

Research Associate

IMD International

Chemin de Bellerive 23

1001 Lausanne

Switzerland

E-mail: karin.oppegaard@imd.ch

Tel: +41 21 618 0240

Fax: +41 21 618 0707

Copyright

©

Catherine A. Ramus and Karin Oppegaard

March 2007, All Rights Reserved

1

Integrating Compliance-based and Commitment-based Approaches in

Corporate Sustainability Management

Businesses have a tremendous impact on the state of the natural environment.

1

Consequently, scholars of corporate sustainability management often express disappointment and frustration at the pace of change and the difficulty in moving from incremental shifts to larger, more holistic evolutions to address the unsustainable nature of most businesses (Shrivastava, 1995). Environmental sustainability is a process, not an outcome, and as such it requires each company which aims at it to have a strategy and a sustainability management system in place that allow environmental and social changes to occur over time (Ramus, 2003)

2

. It also involves balancing issues of values and commitment (which are inherently normative) with issues of efficiency and compliance (implementing changes). In this paper we suggest that one barrier to more evolutionary change may be a dichotomous conception of what drives environmental sustainability (i.e. either commitment or compliance). We argue that commitment and compliance-based approaches can coexist to the benefit of organizations wishing to move toward environmental sustainability.

1

An underlying assumption in our work is that organizations have reasons to wish to increase the sustainability of their businesses. This is not to say that all businesses whole-heartedly embrace and commit to environmental sustainability as a goal. But, assuming that public and governmental pressure for such advances will not disappear in the future, business organizations will need to focus some attention on sustainability to satisfy the needs of those in the societies in which they operate. Global climate change, polluted and scarce water supplies, polluted land and air, and endangered species, are only a handful of the environmental issues that will not go away in the foreseeable future (Brown,

2003; Meadows, Randers, & Meadows, 2004; Worldwatch Institute, 2004).

2

Sustainable development is defined as ensuring that we meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (World Commission on

Environment and Development, 1987). Many see sustainability in organizations as a three-legged stool with economic, environmental and social concerns each representing one leg of the stool. In this paper we acknowledge that most businesses focus the majority of their energy on the economic leg of the stool, working each day to stay in business by producing goods and/ or services at a profit. Without going into the debate on what should normatively be the main issue of concern for businesses, in this paper we focus on how organizations can more effectively manage environmental issues with which they are increasingly being confronted.

2

Moving towards sustainability requires huge shifts in business operations, including the rethinking of product and service offerings. Examples of organizational actions that increase environmental sustainability include shifting from manufacturing products to servicing products, improving energy-efficiency of products and manufacturing processes, reducing/ changing materials used in products/ services, extending the life of products, and designing product components for reuse.

Scholars have emphasized how the nature of corporate environmental sustainability makes it unique to organizations

3

. For example, sustainability is far reaching in time and scope, implying both short and long term effects and multiple constituents with varying interests. It rests on values that concern personal, others’, and future generations’ interests (or, as Sternberg, 1998, puts it, a balance of intra-, inter-, and extra-personal interests). It is organic in the form and it affects multiple levels in organizations (Starik & Rands, 1995). Environmental issues differ from other social issues in that they are more systemic and thus tend to impact a larger number of organizational functions (Post & Altman, 1992). In sum, scholars have argued that short-term, incremental changes are insufficient to move an organization to sustainability; rather, long-term, creative and holistic efforts are required (Starik &

Marcus, 2000; Starik & Rands, 1995).

But while sustainability is organic in form, complex, multilevel, multisystem, and involves systemic interdependencies, in order for businesses to sustain long term efforts in the movement toward sustainability, they need to find a way to balance idealism/ vision with practical capabilities/ implementation

.

When an organization approaches sustainability with a limited focus on compliance to external, isolated events, it tends to result in sustainability initiatives that are ad-hoc and reactive (Winn

3

When we use the term “sustainability” in this paper we are referring to environmental sustainability in business organizations.

3

& Angell, 2000), piece-meal and end-of-pipe (Russo & Fouts, 1997), and decoupled

(Weaver, Trevino, & Cochran, 1999a). Indeed, scholars looking at compliance-based approaches have highlighted many types of disjointed organizational responses: discrepancy between top management discourse and actual organizational practices

(Winn & Angell, 2000); disconnection between the proclaimed ( published policies ) and the enacted ( implementation ) (Ramus & Montiel, 2005); incoherencies between the personal values of organizational members and their performance incentives

(Sheldon, Turban, Brown, Barrick, & Judge, 2003); and, decoupling between initiatives and the rest of the company’s strategy (Weaver, et al.

, 1999a). To avoid these types of decoupling, scholars have asserted that there are benefits from integrating values – both personal and organizational-- into organizational processes when managing issues of corporate sustainability and responsibility (Post & Altman,

1992; Weaver et al.

, 1999a; Whetten & Mackey, 2002; Winn & Angell, 2000).

In an attempt to move away from dichotomous thinking, we argue in this paper that achieving a balance between idealism and practical implementation requires an integration of commitment- and compliance-based approaches to sustainability management. We define compliance-based approaches as organizational processes that focus on reacting to events or pressures external to the organization. For example, organizations can have processes and systems in place for ensuring timely and appropriate responses to institutional (external stakeholder) pressures. We define commitment-based approaches as being driven by internal, value-based processes, involving an appeal to organizational norms and personal values of organizational members. Commitment is less reactive and less goal-oriented than compliance. Its desired end is not to satisfy an external stakeholder or public, but rather to include processes and systems whereby people can express personal values

4

and the organization as a whole develops common understandings and norms related to sustainability management. We assume the motivators and assumptions underlying these approaches are often different but not mutually exclusive.

Furthermore, the systemic nature of sustainability makes each organization unique in the way it manages sustainability. As such, the integration of value-driven with implementation-focused processes will be achieved differentially in each case, depending on a series of characteristics unique to each organization. For example, an organization’s specific industry, culture, values, history, management philosophy, top management commitment, control systems, and monitoring mechanisms may affect its approach to managing sustainability issues.

4

The relative degree of commitment-based and compliance-based effort for sustainability is reflected on all levels of the organization: at top management/ strategic, managerial, and individual employee levels. In other terms, at all these levels, environmentally responsible behavior can be more or less subject to compliance and control or chosen voluntarily, based on commitment and values.

Many authors have addressed this tension between commitment/ volition versus compliance/ control, and have examined their antecedents and consequences at different organizational levels and functions (e.g. Carroll, 1979; Hart, 1995; Maignan

& Ferrell, 2004; McWilliams, Siegel, & Wright, 2006; Post & Altman, 1992; Russo

& Fouts, 1997; Sharma, 2000; Shrivastava, 1995; Starik & Rands, 1995; Winn &

Angell, 2000; Weaver & Trevino, 2001). However, missing in this literature is a model that identifies how commitment and compliance-based approaches can coexist and even positively interact at various levels in organizations.

4

Our purpose in this paper is not to examine what makes organizations’ approaches unique, but rather to indicate that organizations will take different paths toward managing sustainability .

5

Our contribution is in creating an integrative model that encourages an understanding of how a specific set of organizational mechanisms affect organizational action in favor of sustainability. These mechanisms include triggers spurring environmental management, organizational responsiveness and strategies, and management tools which affect managerial discretion and employee motivation.

Our interest is to show how these sets of mechanisms interact to promote (or fail to promote) movement toward environmental sustainability. In our first model, we look at how these mechanisms exist on continuums ranging from extreme reactivity and minimum compliance to commitment-based and voluntary effort for sustainability.

This first model also illustrates how formal, control-based management processes tend to coincide with compliance-based approaches, and informal, value-based management processes tend to coincide with commitment-based approaches.

We propose a second model which describes how, within an organization, formal and informal management tools can interact to influence change in favor of sustainability management. More specifically, we highlight how formal, control-based systems can positively interact with informal, value-based orientations to affect positive change for sustainability over time. This process model illustrates how different organizations might take different paths toward sustainability, by integrating both compliance and commitment-based approaches in their own, organizationspecific manner.

This paper is structured as follows. We briefly review the corporate sustainability literature, indicating the gaps that we propose to fill with our conceptual work. Then we build our first model and second model using the literatures from the pertinent domains. Finally, we discuss how our work contributes to a greater understanding of sustainability management processes in organizations.

6

CONCEPTUAL BASIS FOR THE INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORK

In this section we will not to present a comprehensive review of the corporate greening, sustainability management, and corporate environmental management literatures

5

, nor develop an argument for why corporations should address sustainability. Others have made the case for the importance of environmental management in companies (Brown, 2003; Meadows, Randers, & Meadows, 2004;

Shrivastava, 1995) and the need for environmental management research (Starik &

Marcus, 2000). Rather we will highlight the literature which is relevant to our intention to build an integrative model of mechanisms affecting sustainability management in businesses. We will focus on presenting literature that calls for and informs such an integrative model.

Calls for Theory

Gladwin (1993) and, more recently, Starik and Marcus (2000) and Sharma

(2002) have called for corporate sustainability researchers to focus their attentions on theory-building. Corporate sustainability scholars have highlighted the need for theories that effectively conceptualize the deeply systemic nature of sustainability issues (Starik & Rands, 1995) and how these issues affect all of levels of organizational functioning (Post and Altman, 1992).

The challenge for those interested in theory-building in the domain of corporate sustainability is finding ways to bring together the various threads of recent research on organizational processes. For example, scholarship has focused on the importance of proactive (Post & Altman, 1992), innovative (Hostager, Neil, Decker,

& Lorenz, 1998), preventive (Hart, 1995; Russo & Fouts, 1997), and voluntary

(Aragòn-Correa, Fernando, & Senise-Barrio, 2004; Sharma, 2000) processes for

5

We will refer to this research domain by the name of “corporate sustainability”.

7

advancing sustainability. Winn and Angell (2000) argued that progress towards sustainability cannot be achieved if one does not acknowledge the fundamental values and motivations that drive the process (see also Gladwin and Kennelly, 1995).

Achieving sustainability implies not only technological change but also a profound challenging of the goals and assumptions driving corporate activities and processes

(Post & Altman, 1992). We have chosen to focus our conceptual work on examining organizational norms, strategies, and processes that affect the degree of proactivity, innovation, and voluntarism across functions and levels in organizations.

Calls for Integrative Theory

Starik and Marcus (2000: 543)) called for future research to “involve more attention to integration… ” (our bold). Sharma (2002: 12) echoes this call encouraging scholarship that integrates “organizational and individual variables” which influence the evolution of organizational greening. Still other scholars have indicated the need for theories that realistically integrate themes of compliance, control, and effective implementation, with themes that are more normative, valuedriven, and commitment-based (Fischer & Schot, 1993; Ramus, 2005; Sharma, 2000;

Winn & Angell, 2000). Our work here is in keeping with the perceived need for nuancing the dominant perspective, which has tended to oppose normativity and instrumentality (e.g. Crane, 2000), with one that acknowledges the grey zones that might exist between these two extremes (see Post & Altman, 1992).

According to Starik and Rands (1995), sustainability management systems can include both integration mechanisms and coordination devices. Integration mechanisms include shared values, roles, and norms (Katz & Kahn, 1978). These integration mechanisms tend to correspond in our model to commitment-based approaches and informal management tools. Coordination devices, on the other hand,

8

include strategies, objectives, plans, schedules, and rules and regulations (Katz &

Kahn, 1978). Coordination devices tend to correspond in our model to compliancebased approaches and formal management tools. We extend previous sustainability research by demonstrating how both formal, control-based systems and informal, value-based systems can coexist providing a conceptual picture of how integration processes can function.

In sum, previous research has called for integrative, process-oriented theories which address various levels within organizations. We address this call in the remainder of this paper, presenting two integrative models that attempt to address these gaps in the corporate sustainability literature. Our overall aim is to paint “a more comprehensive picture of the multiple, complex paths of corporate greening ”

(Winn & Angell, 2000: 1143, our bold). We hope that our integrative model will contribute order and nuance to a field that has been marked by many diverging streams of thought.

COMMITMENT AND COMPLIANCE IN

SUSTAINABILITY MANAGEMENT: TWO INTEGRATIVE MODELS

In this section we will present two models. In the first model we integrate various conceptual approaches to sustainability management that have either tended to exist in isolation or opposition to each other. The first model illustrates how the drivers for sustainability can be conceptualized as existing on a series of spectrums or continuums, ranging from compliance, on one pole, to commitment, on the other.

After this static model, we will present a second model which describes the dynamic interactions that might exist between commitment- and compliance-based approaches

9

across the various mechanisms described, and how these dynamics unfold both horizontally and vertically in the organization.

Model One: Mechanisms for Managing Sustainability along the Continuum of

Compliance and Commitment-based Approaches

In figure one we show six mechanisms for managing sustainability—trigger, environmental responsiveness, strategic framing, management tools, managerial discretion, and employee motivation. These six mechanisms are grouped into three phases. In phase one we include the “trigger” mechanism which acts as an impetus and occurs before an organizational response to sustainability. The two mechanisms of “mode of responsiveness” and “strategic framing” are included in phase two, which occurs when the organization is interpreting the issue of sustainability and preparing discretion”, and “employee motivation” are included in phase three, which occurs when the organization is implementing its strategic response to sustainability. In actuality often all three of these phases occur simultaneously, with an organization receiving new triggers, developing new interpretations, and implementing its strategic mechanisms, we think it is useful to conceptually differentiate in this model between the phases so that one can more clearly theorize how a trigger spurs the organization to develop a mode of responsiveness and strategic framing of the issues, after which it uses management tools that encourage implementation and different levels of managerial discretion and employee motivation. We also acknowledge that these phases might even occur in the opposite direction, for example in the form of "grass-

10

root" and bottom-up processes driven by managerial discretion and/ or intrinsic employee motivation (Ramus, 2005; Winn & Angell, 2000).

Before we proceed to define the six mechanisms it is important to acknowledge that these six categories may involve different types of organizational actors. Previous work has used functional categories to delineate who in the organization uses different modes of responsiveness to sustainability (Post & Altman,

1992). Here we take a different approach. First, we acknowledge that the mechanisms in our model potentially involve different external and internal actors. For example,

“trigger” may take the form of institutional pressures (coming from government, nongovernmental organizations, competitors, and other societal stakeholders) or the result of internal organizational values and culture that are developed over time by interactions between different levels of organizational actors including top management, line management, and employees who work in different functional areas. What is different about our conceptual model is that it doesn’t presume that top management or external stakeholders are the only actors that influence the form that sustainability takes in an organization. Instead, by using compliance-based and commitment-based approaches as the organizing concepts for the model, we propose that depending on where the organization is along the continuum for each mechanism

(1 through 6), different organizational actors and stakeholders will be empowered or disempowered to influence and implement sustainability.

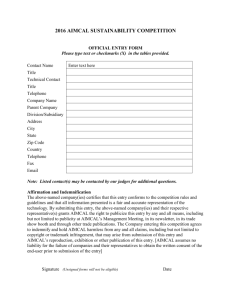

------- INSERT FIGURE ONE ABOUT HERE------

Horizontal Continuums: Compliance to Commitment. Each of the six mechanisms is presented along a continuum ranging from compliance to commitment. (When discussing model one we start on the left hand side and move to the right.) The case

11

where there is no organizational response is on the far left-hand column of this continuum: in practice some organizations choose to ignore sustainability and develop no mechanisms for managing it.

Several scholars have used continuums to describe organizational strategies for managing corporate responsibility and environmental sustainability. Our horizontal continuums of compliance to commitment are, for example, informed by

Carroll’s (1979) corporate responsibility theory. Carroll (1979) described a continuum of responses ranging from “no response”, to strict compliance to government regulations in order to stay in business (what we call “compliance”) to “voluntary” and “proactive” efforts (what we call “commitment). Similarly, Post and Altman’s

(1992) corporate sustainability theory described a continuum of progress towards achieving sustainability, ranging from “adjustment” (reactive response to regulations/ minimum compliance), “adaptation” (active response to external pressures/ full compliance), to “innovation” (integration of environmental approaches into organizational processes). We will go into more detail below on how previous scholarship has informed our choices of the continuums. The numbers before each definition corresponds to a mechanism (bearing the same number) on a horizontal line of figure one.

(1) Trigger—We define a “trigger” as an attention-based mechanism that creates volition within an organization to manage sustainability .

Post and Altman (1992) noted how a mix of internal and external factors influenced corporate environmental action. When a trigger comes from an external stakeholder

(e.g. government regulations, market and consumer pressures, financial institution rankings), it often leads to compliance-based approaches. Whereas, when a trigger

12

comes from organizational culture and norms, it occurs because internal stakeholders have a commitment to the issue.

Many scholars have highlighted the role of external stakeholders as the predominant mechanism for spurring organizational responses to sustainability

(Henriques & Sadorsky, 1999; Margolis & Walsh, 2003; Ramus, 2003). Often the only trigger for sustainability management is external compliance pressures (e.g., the media, regulators, community stakeholders). In the extreme, this means that sustainability issues are only considered if a salient external event occurs. For example, media coverage may have highlighted a risk to corporate reputation, government may have promulgated a new regulation, or community members may be angry about pollution coming from a factory. This corresponds to what Post and

Altman (1992: 9) described as the “concrete level” of firm motivation for sustainability, i.e. “financial considerations, regulatory requirements, and environmental disasters”.

However, sustainability processes are not necessarily triggered by external events. As stated by Maignan and Ferrell (2004: 9/10), “the organization’s own norms may stimulate a commitment to a specific cause independently of any stakeholder pressure. These organizational norms may also exceed stakeholder norms with respect to particular issues.” In this case, which corresponds to Post and Altman’s (1992)

“abstract” level of environmental motivators of firms, efforts for corporate sustainability can be initiated by employees from any layer in the organization (Winn

& Angell, 2000), provided the organizational culture permits these initiatives (Ramus,

2005). For example, an employee might care about saving trees and propose a paper recycling program, a line manager might wish to reduce the firm’s impact on climate change and support the development of an energy efficient product or service, or a

13

senior executive might push to integrate sustainability goals in the organization’s overall strategy because s/he has a personal commitment to protecting nature. Thus, in the case of environmentally-responsible organizations, commitment to sustainability is likely to originate from its members’ personal value systems. These value systems may preexist employment with the organization, or be developed during involvement in sustainability-related activities at work.

(2) Mode of Responsiveness—We define a “mode of responsiveness” as a set of norms that guide the mechanisms chosen by the organization to manage sustainability.

An organization’s mode of responsiveness corresponds to its manner or philosophy of response, rather than the concrete content of the issue addressed (Carroll, 1979). As such it is embedded in the organization’s values, norms and culture. These values correspond to the acceptable means for achieving a given outcome and strongly influence a firm’s structure and strategy (Bansal, 2003), as well as issue legitimacy

(Sharma, 2000)

Environmental responsiveness can range from an absence of response, a reactive response, a proactive response, to a voluntary and interactive response (Post

& Altman, 1992). “No response” in model one corresponds to an organization that simply ignores external and internal pressures for environmental sustainability.

A compliance-based mode of responsiveness focuses on living up to the expectations of external stakeholders, regulators, the media, etc. Compliance-based modes of responsiveness have also been labeled defensive/reactive (Winn & Angell,

2000), conformist (Sharma, 2000), and end-of-pipe (Russo & Fouts, 1997). A reactive response tends to be initiated by top managers and to be limited to actions that address isolated demands made upon the organization.

14

When an organization’s mode of responsiveness is more proactive, anticipatory, and preventive, more room is given to value-based drivers and internal commitment. As such, moving along the continuum to the right, we find proactive approaches, which focus on prevention and innovation (Russo & Fouts, 1997).

Organizations which are proactive in their responsiveness tend to be better at detecting subtle signals of what is needed to increase organizational sustainability in the longer term.

On the extreme right-hand side of the continuum we find commitment-based approaches that include voluntary and interactive modes of responsiveness (Post &

Altman, 1992). Voluntary responsiveness is in keeping with Carroll’s (1979: 500) notion related to organizational discretion:

“Discretionary (or volitional) responsibilities are those about which society has no clear-cut message for business – even less so than in the case of ethical responsibilities. They are left to individual judgment and choice. […] These roles are purely voluntary, and the decision to assume them is guided only by a business’s desire to engage in social roles not mandated, not required by law, and not even generally expected of businesses in an ethical sense”.

A voluntary and interactive mode of responsiveness is beyond adjusting and adapting to environmental issues. Organizations that engage in voluntary and interactive responsiveness tend to have norms that support a more profound dialogue with internal and external stakeholders, creating a sort of osmosis that may blur the frontiers of the organization, and in this way better integrate environmental concerns into the organization’s way of operating.

(3) Strategic Framing—We define “strategic framing” as how an organization interprets and makes sense of sustainability in order to use organizational resources to achieve sustainability .

Strategic framing can range from specific, one-time strategies based on isolated threats or opportunities, to an integrated strategic orientation in which sustainability is

15

considered in a pervasive manner throughout the company’s activities. In this section we first describe the strategic framing continuum of the model, and then we identify how strategic framing relates to integration of environmental sustainability in an organizational setting.

When the organizational focus is mainly on compliance, strategic orientations can range from seeing the issues as a “threat” to seeing it as an “opportunity”. When seen as a threat, an organization’s strategic framing of sustainability issues will be focused on using organizational resources to deal with isolated negative events when they occur. Russo and Fouts (1997) called this an “end-of pipe approach”. Sharma

(2000) called this “an environmental strategy of conformance”. Winn and Angell

(2000:1130) call this strategic approach “deliberately reactive” explaining that in this case the organization will “engage in specific environmental activities only when forced to do so by regulatory authorities or other external pressures”.

The more a positive and proactive view of compliance to external pressures is chosen, the more sustainability is seen as an opportunity (Sharma, 2000), and the more focus is given to prevention (Russo & Fouts, 1997). Sometimes a compliancebased strategic framing involves seeking opportunities for competitive advantage

(Porter & Kramer, 2002; Yaziji, 2005). However, in compliance-based approaches, the overarching goal remains to enhance the bottom line (Post & Altman, 1992;

Margolis & Walsh, 2003).

On the far right-hand side of the continuum, we depict strategic framings that more broadly embrace integration of sustainability into organizational processes. In this case, there is a pervasive, encompassing presence of sustainability goals throughout the organization’s strategy, and environmental impact is considered in daily strategic decision-making. In other terms, environmental commitment becomes

16

manifested in “a consistent pattern of company actions taken to reduce the environmental impact of operations, not to fulfill environmental regulations or to conform to standard practices ” (Sharma 2000: 683). A strategy of integration encourages more systematic and proactive implementation of environmental policies in diverse areas and functions of the organization (Post & Altman, 1992; Winn &

Angell, 2000) as well as innovation (Hart, 1995).

Integrating Sustainability through Strategic Framing.

Commitment-based approaches allow strategies and policies to be more holistically integrated based on shared values, resulting in a streamlining of these ideas and initiatives with the organization’s general strategy, policies, and practices. Post and Altman (1992) suggested that when environmental issues are integrated using organizational learning processes, the result can be second-order changes in which the very culture and mindset related to sustainability is fundamentally modified. (We will define and discuss the relevance of organizational learning processes to sustainability below.)

Importantly, though, commitment-based strategies are more complex and demand more radical organizational change than simple compliance. “Prevention is a more comprehensive and socially complex process than compliance, necessitating significant employee involvement, cross-disciplinary coordination and integration, and a forward-thinking managerial style” (Russo & Fouts, 1997: 538).

Indeed, when sustainability becomes an integrated part of the company philosophy and behavior, sustainability is beyond strategy .

It becomes part of “who we are as an organization” (Whetten & Mackey, 2002: 394). In this case, a strategy derived from a commitment-based approach becomes an integral part of an organization’s image and identity and thus more largely guides the actions and decisions of its members (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991).

17

As discussed above, mechanisms 2 and 3 in our model involve organizational responses and issue interpretation. Mechanisms 4, 5, and 6, described below, are mechanisms for implementing organizational changes related to sustainability.

(4) Management Tools—We define “managerial tools” as mechanisms used by organizational members to implement the organization’s strategic intentions related to sustainability.

The actual implementation of the above-mentioned strategies relies on the usage of various management tools. The management tools continuum ranges from an absence of tools for implementing environmental policies, formal/ control-oriented management practices, to informal/ value-based orientations to implementing a sustainability program. In this section, after describing the management tools continuum we discuss the pros and cons of formal control systems as compared to informal, value-based management systems.

On the left-hand side of the management tools continuum we note that there are “no tools”. An organization might do nothing to implement an environmental strategy. As described by Ramus and Montiel (2005), many companies simply pay lip-service to sustainability issues, and publish formal policies, but do not implement these policies.

When an organization sees sustainability as an important strategic issue, then it may choose compliance-based approaches that include formal, control-oriented management tools. Formal, control-oriented management often takes the form of implementation of an environmental policy and/ or program. In this case managers in the organization will often rely on control systems that include formal performance reviews coupled with sanction and reward systems (Adler & Borys, 1996; Etzioni,

1961; Scott & Meyer, 1991). Management may focus primarily on ensuring members’ behaviors are aligned with the goals set forth in the environmental policies, and on

18

monitoring behavior on the basis of measurable indicators (Weaver & Trevino, 2001;

Weaver et al .,1999a; Oppegaard & Statler, 2005). Such top-down, complianceoriented management tools frequently characterize sustainability management

(Ramus, 2001).

Further right towards the commitment-side of the continuum, we find approaches that are informal and value-based. These approaches are often based on an appeal to corporate identity, norms, individual values and commitment. As noted by

Sharma (2000: 692), “managers who perceive environmental protection as an integral part of their corporation’s identity may not need formal controls and incentives to act accordingly”. When commitment-based management tools are employed effectively, the organization allocates time and resources for establishing a dialogue in which values are discussed, personal commitment is encouraged, and managers use organizational learning behaviors to encourage employees to integrate environmental values to their on-the-job identities (Ramus & Steger, 2000).

By definition, learning organizations are designed to support innovation, employee creativity, and a culture and managerial behaviors that allow learning and information transfer throughout the organization (see Argyris & Schon, 1978; Ferris

& Fanelli, 1996; Garvin, 1993; Pearn, Roderick, & Mulrooney, 1995; Peters, 1990,

1991; Senge, 1990; Wagner, 1991). Specific managerial behaviors in such organizations include supporting employee environmental initiatives, information dissemination, competence building, role modeling responsible behavior, providing social recognition, and communicating about sustainability making the issue visible and a legitimate concern (Ramus, 2001).

Pros and Cons of Control versus Value-based Environmental

Management.

Control systems, in general, are established by management to provide

19

for a standardization of behavior, allowing “stable expectations to be formed by each member of the group as to the behavior of the other members under specific conditions” (Simon, 1957: 100). Control-oriented management has its origins in scientific management theory (e.g. Taylor, 1911; Fayol, 1916) and is described by

Lawler (1992) as bureaucratic and hierarchical, with employees’ work being controlled using vertical relationships (Russo & Fouts, 1997; see also March &

Simon, 1958). Managers often use a system of incentives/ disincentives (rewards, sanctions, performance evaluations) to ensure employees comply with the organizational goals (see Egri and Hornal (2002) for a review of environmental human resource management tools).

Control systems are good for motivating individuals who would not otherwise take discretionary actions for sustainability because this type of system sets concrete goals, measures performance against those goals, and provides a benchmark for assigning rewards. An increase of environmentally responsible employee behavior is likely to occur when this type of behavior is formally required and evaluated. This is because evaluation can result in heightened employee awareness and sensitivity to the environmental issue, lead to communication describing appropriate employee behavior, and legitimize using time and resources for sustainability on-the-job

(Weaver & Trevino, 1999; Egri & Hornal, 2002). In some cases, a formal control system will lead to the environmentally responsible behavior becoming an inrole task, and part of the employee’s job description.

Unfortunately, control systems can limit creativity and autonomy necessary for intrinsically motivated employees to flourish as change agents (Amabile, Hill &

Tighe, 1994). In general, intrinsically motivated individuals do not value the reward

20

as much as they value the task itself, and their efforts are based in self-espoused values, not in external goals (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Recently, authors have identified the importance of value-based management tools in which formal policies and procedures are less important than appealing to employees’ personal values, self-espoused aspirations, and self-concept (Weaver &

Trevino, 1999; Weaver, Trevino, & Cochran, 1999b; Weaver & Trevino, 2001).

Weaver and Trevino (2001) have shown that a value-based orientation fosters employee commitment to ethics. As highlighted by Russo and Fouts (1997:539) in the case of environmental management: “although a bureaucratic management style may be matched to compliance, use of a more organic style is necessary to capture the gains associated with going beyond compliance, because the latter generates the type of innovative culture (…) that enhances prevention efforts”.

Scholars have discussed the danger of an exclusively value-based approach.

An excessive focus on values in the absence of concrete tools, can lead to problems with implementation. “A lack of formal planning and little monitoring of internal environmental performance or external developments leave the firm unprepared for new developments. Organizations in this category exhibit a strong policy commitment, in the absence of a proactive approach to implementation” (Winn &

Angell, 2000: 1131).

Above we have reflected on how compliance and commitment-based approaches circumscribe different types of management tools. Below we discuss how commitment and compliance-based approaches manifest themselves in perceived managerial discretion (5) and employee motivation (6).

(5) Managerial Discretion— We define “managerial discretion” as the collective set of individual managers’ perceptions of latitude and resources

21

available to them to implement and innovate based upon their own values related to sustainability in an organization

6

.

In model one we present the continuum of “managerial discretion” ranging from nonexistent, low (on the compliance side), to high (on the commitment side).

Compliance-based approaches tend to give little discretion to managers, whereas commitment-based approaches tend to give higher levels of discretion to managers.

Below we will discuss the importance of managerial discretion to the implementation of environmental programs.

Researchers have demonstrated the importance of managers’ actions in encouraging sustainable business practices (e.g. Aragòn-Correa, et al.

, 2004; Cordano

& Frieze, 2000; Ramus & Steger, 2000; Sharma, 2000). For example, Winn and

Angell (2000) emphasized management’s role in implementing sustainability policies.

Sharma (2000) and Aragòn-Correa and colleagues (2004) demonstrated the importance of encouraging managers to act voluntarily on their commitment to environmental values. According to Winn and Angell (2000: 1141), discretionary behavior is the means by which “individual ‘champions’ may push their limited budgets and authority beyond compliance”.

Our definition of managerial discretion is consistent with other scholars who have defined it as latitude of action, resulting from both perceptual (intra-personal) and contextual (organizational) determinants (Carpenter & Golden, 1997; Hambrick

& Finkelstein, 1987; Key, 2002; Shen & Cho, 2005). Perceived discretion becomes increasingly important in the zones where policies, codes and mission statements are too vague to give concrete guidance (Key, 2002; see also Finkelstein & Hambrick,

6

Managers, like all individuals, carry their own individual value-systems. We are not arguing that all managers will value environmental protection or sustainability. We are speaking of the discretion available to those who do have an inclination towards acting upon pro-environmental values.

22

1990). The more informal is the management system, the greater the importance of perceived managerial discretion.

As highlighted by Hambrick and Finkelstein (1987), discretionary activities are, by definition, driven by values. In the case of environmental sustainability, discretion can be seen as perceived freedom to enact values related to the environment, encouraging the managers to make use of information, resources, and directives in ways that promote sustainability (Winn & Angell, 2000). Offering managers discretion for sustainability involves allowing them autonomy of action, resources for projects, and time to manage them. As noted by Sharma (2000: 691),

“strategic leaders need to legitimate environmental issues as an integral part of the corporate identity while allowing managers time and resources they can apply at their discretion to creative problem solving”. Provided managers in the organization collectively have personal values related to protecting the environment and sufficient discretionary slack and resources to act on these values (Sharma, 2000), managerial discretion can be used as part of an organization’s informal management practices for promoting sustainability.

(6) Employee Motivation—We define “employee motivation” for environmentally responsible behaviour as determined by the collective perceptions by the employees of the perceived degree of organizational control versus personal volition related to sustainability .

Employees can have no motivation to behave in an environmentally responsible manner in the workplace, or they can have behavior that is motivated somewhere on a continuum between extrinsically to intrinsically motivated. Where employees fall on the extrinsically to intrinsically motivated continuum depends largely on the social context (Sheldon et al., 2003). Organizations can both encourage employees to comply with codes of behavior related to responsibility (left side of the continuum), as

23

well as encourage them to voluntarily propose initiatives and act on the basis of personal commitment to sustainability (right side of the continuum).

Individual behavior based on compliance is extrinsically motivated.

Extrinsically motivated behavior is also termed “controlled”, as it is only displayed under the presence of salient external control (Ryan & Deci, 2000; see also Kelman,

1958). Such motivation is driven by the attainment of external goals (Deci & Ryan,

1987; Sheldon et al., 2003), and provides compliance with organizational objectives, in our case, a minimum level of employee behavior respectful of the environment. An organization wishing to promote extrinsically motivated behavior can set individual environmental goals for employees, evaluate employee performance against these goals, and use rewards or sanctions behavior related to these goals.

Intrinsically motivated behavior, on the other hand, is voluntary employee effort for the natural environment. When behavior is based in self-espoused values, not in externally defined goals, it is intrinsically-motivated (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In other terms, what drives intrinsically motivated behavior is a sense of coherence between one’s self-concept and the action (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Shamir, House, &

Arthur, 1993). Intrinsic motivation has been shown to lead to engagement, creativity, cognitive flexibility, competence, trust, and volition (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Amabile et al.

, 1994). An organization wishing to promote intrinsically motivated behavior can encourage bottom-up, top-down and cross-organizational communication (dialoguing around environmental values), provide time and resources for training and competence building related to environmental problem-solving and innovation, provide time and resources for experimenting with environmental ideas, and signal through top and line management role-modeling that environmentally responsible behavior is encouraged.

24

Of particular interest to the case we are making here is the link between intrinsic motivation and creativity (see the work by Amabile and her colleagues,

1994; 1996; 1997). Given that sustainability demands that companies find new solutions to existing problems, innovate in the use of technology and management systems, and rethink the way the firm is dealing with waste and other negative impacts on the environment and society in general, employee creativity is valuable for sustainability management (see Hostager et al.

, 1998). For example, employee environmentally responsible behavior might include helping improve the company’s social and environmental performance (Wood, 1991), by proposing eco-initiatives

(Ramus & Steger, 2000), and displaying socially responsible behavior (Schneider,

Oppegaard, Zollo, & Huy, 2004). In other terms, encouraging employee autonomy in proposing solutions to environmental problems and leveraging the creative potential residing in employee intrinsic motivation for sustainability depends on integrating value-based practices in sustainability management.

Finally, while organizations may wish to benefit from employees’ intrinsic motivation for the sake of improving environmental sustainability, they may also find other benefits related to increased employee motivation from adopting management tools that encourage employee’s to act on their personal commitment to environmental sustainability. We suggest this because there is some evidence that a growing number of individuals see themselves as environmentally-concerned (The

Environmental Two Step, 1995). We also know that employees are increasingly trying to reconcile professional and personal value systems by promoting social change (Chatman, 1989, 1991; Hoffman, 2003; Ramus, 2005). Acting on intrinsic motivation related to sustainability when it corresponds to their self-concept may enhance employees’ feelings that they “fit” in the organization (Chatman, 1989).

25

In sum, the more organizational members perceive their behavior to be controlled , the more they will focus on compliance with organizational demands, i.e. be extrinsically motivated. On the other hand, the more autonomy organizational members feel, the more they will be intrinsically motivated. The drivers for intrinsically motivated behavior are feelings of personal autonomy and an internal sense of responsibility to actively participate in the organization’s sustainability efforts. In addition to being satisfying for the individual employees, encouraging autonomous action helps the organization leverage the specific knowledge, competencies, and creativity of employees potentially resulting in efforts that are neither paid for nor evaluated.

Model Two: Dynamics of Integrating Compliance and Commitment-based

Approaches in Sustainability Management

Using model one we have discussed the mechanisms through which organizations may foster environmental management. Below we present a second model (see figure two) aimed at demonstrating the potential interactions that can occur when both compliance and commitment-based approaches coexist in an organizational setting. Weick and colleagues (1999:197) have asserted that acceptance of paradoxes can create highly effective systems, for example, when organizations simultaneously pursue “opposites such as rigidity and flexibility, confidence and wariness, compliance and discretion , anticipation and resilience, expertise and ignorance, and balance them rather than try to resolve them” (our bold).

With model two we intend to demonstrate that effective organizations can rely on complex systems for pursuing different objectives, and that there is no need for an

26

organization to choose definitively between compliance and commitment-based approaches.

Underlying model two are a couple of assumptions. First, we assume that integration of compliance-based and commitment-based approaches to managing sustainability may be preferable to the alternative of being solely focused on compliance or commitment. In our view neither approach is superior to the other.

Without effective formal organizational control systems little may get done (Epstein,

1996). And without openness to developing organizational norms of respect for the natural environment, sustainability would appear to be unachievable (Starik & Rands,

1995). Therefore, in model two we examine how formal and informal management tools can work together to encourage values and commitment to sustainability using effective tools to measure and manage implementation.

In model one we have seen how compliance-based and commitment-based approaches in sustainability can be conceptualized as existing on continuums. We have asserted that a specific organization may be situated somewhere between the two poles of the continuums. Our second assumption underlying model two is that, although exceptions will obviously exist, in reality many organizations will be situated somewhere between the two extremes.

----- INSERT FIGURE TWO ABOUT HERE -----

Figure two shows a process model including both vertical and horizontal dynamics. First we describe the potential interactions (vertical interdependencies) that may exist within and between levels 1, 2, 3 and 4 of model two. Then we describe the dynamic processes between control systems and value-based orientations that can

27

potentially exist between levels 4, 5, and 6 in model two. We define “control systems” as processes and tools that are formal in nature, encouraging compliance with organizational strategies, policies and goals related to environmental management.

We define “value-based orientations” as informal management processes and tools that encourage shared norms related to sustainability.

Vertical Interdependencies between Triggers, Mode of Responsiveness,

Strategic Framing and Management Tools. Model two shows how the nature of initial triggers, modes of responsiveness, strategic framing, and choice of management tools will tend to go together (see solid arrows pointing downward in figure two).

A focus on compliance to external pressures tends to lead to reactive and conformance-based modes of environmental responsiveness, a view of sustainability events as occurring as isolated strategic issues, and the use of formal tools and control-systems. Conversely, when internal commitment fosters sustainability efforts, environmentally responsible behavior will tend be triggered by organizational norms, align with modes of responsiveness that are voluntary, and environmental strategies that are integrated, with the organization often using informal management tools focused on shared values. It is important to reiterate, however, that each organization will balance compliance- and commitment-based approaches differentially. In model two the downward pointing arrows from “compliance” to “control systems” and from

“commitment” to “value-based orientations” point to large tendencies and not deterministic relationships.

Yet, while there may be a tendency for an organization to be primarily compliance or primarily commitment-based in its approach, the literature would suggest that nuances exist between these two approaches. Thus, in figure 2 we include

28

the horizontal dynamics through which commitment and compliance can interact (see the dotted lines of figure two).

(1) Trigger: an organizational focus on external pressure “triggers” does not necessarily exclude a focus on norm- and value-based commitment (see dotted arrow

(a)). For example, Maignan and Ferrell (2004:12) said that “the generation of intelligence about stakeholder communities helps identify new stakeholder issues and may therefore lead to an adjustment of organizational norms”. This point is also highlighted by Sharma (2000) who stated that responses to external pressures might increase issue legitimization, which in turn might influence corporate identity long term.

(2) Mode of Responsiveness: voluntary, commitment-based “modes of responsiveness” can also be coherent with and encompass a strategic focus on opportunities (Sharma, 2000) (dotted arrow (b)).

(3) Strategic Framing: Although “integrated strategic framings” will tend to result in value-based, informal management tools, they might very likely also cooccur with the use of control-based, formal management tools and might actually be more effective this way, in terms of implementation (dotted arrow (c)). (For an illustration of the benefits of combining value-based and control-based approaches, see Weaver and Trevino (1999).)

Conversely, a strategic focus on environmental management as an

“opportunity” does not exclude the usage of value-based orientations in order to achieve strategic targets (Sharma, 2000) (dotted arrow (d)).

Hence, although a compliance-based approach may have different philosophical and attitudinal underpinnings than a commitment-based one, we argue that the two can interact in such a way that it encourages simultaneous use of control

29

systems and value-based orientations. As we discuss below, at the level of

“management tools” (line 4, figure two), control systems and value-based orientations can feed back into each other dynamically, and may ultimately result in an increase of commitment-based processes over time.

Dynamics between Control Systems and Value-based Orientations. We use the lower half of figure two to discuss how both “control systems” and “valuebased orientations” can coexist and positively influence each other to foster movement toward sustainability (see block arrows surrounding words “organizational learning tools”).

(4) Management Tools: As mentioned, Weick and colleagues (1999: 197) showed that highly effective organizations can accept paradoxes and “become more tightly coupled and more interactively complex.” This assertion is in keeping with the learning organization literature that indicates the benefits for organizations that couple formal and informal management tools (Ramus & Steger, 2000; Sharma, 2000; Starik

& Rands, 1995). Organizations may choose to integrate formal and informal management tools not only because of the potential this integration has for moving an organization toward sustainability, but also because of organizational benefits that may extend into other areas of general functioning of the business (Senge, 1990).

Based upon the organizational learning research of Ramus (2003) and Ramus and Steger (2000), we suggest that organizations which desire to coexist with the paradox of embracing commitment and compliance simultaneously can use a series of management tools which these authors showed to be important for encouraging employee environmentally responsible behavior. Informal management tools include bottom-up, non-hierarchical communication, employee participation in environmental decision making, and training and education to build the individual capacity and skills

30

needed for environmental problem-solving (Ramus, 2003). Formal management tools include top down communication of policies, strategies and goals to employees, mandating individual goals and responsibilities related to environmental outcomes, evaluation/ feedback on progress toward the goals, and rewards and recognition including both monetary rewards and non-monetary recognition (Ramus, 2003).

According to Ramus and Steger’s findings (2000) both informal and formal

“organizational learning” tools reinforced employee environmental behaviors, creating a positive dynamic between compliance and commitment-based approaches.

Below we discuss the dynamics that exist between low and high managerial discretion, and extrinsic and intrinsic employee motivation. In particular we highlight how when shared values and norms for sustainability exist, formal and informal management tools can create a positive dynamic moving the organization toward sustainability.

Providing managerial discretion and encouraging employees’ intrinsic motivation will only be effective in promoting environmental sustainability in organizations where managers and employees are concerned about the natural environment (Ramus, 2005). Organizations which wish to promote environmental sustainability, but where the managers and employees do not care about environmental protection, are better off, at least at first, using formal management tools, allowing low managerial discretion, and requiring employees to protect the natural environment through goal-setting, performance evaluation and rewards/sanctions.

(5) Managerial Discretion: We propose that managerial discretion and formal management tools such as setting goals, evaluating employee performance related to these goals, and rewarding behavior can coexist in an organization.

31

Low Discretion: On the compliance side of the continuum, when managers are offered no or low discretion, they have no or little leeway to pursue a role of actively pushing for implementation beyond compliance with company policies (as described in Aragòn-Correa et al.

, 2004). In this case, managers that are committed to environmental sustainability can only function within the limits of official organizational environmental goals. We propose that organizations wishing to move toward sustainability would gain by offering some managerial discretion, provided that some of the managers care about promoting environmental sustainability.

High Discretion: On the right side of the continuum, when managers are offered discretion and they care about the sustainability, then this latitude of action can be used at the service of sustainability (Winn & Angell, 2000). Allowing managers and employees some discretion related to participation, time, resources and training, and encouraging open communication related to environmental values can be effective means for encouraging discretionary and creative environmental behavior.

Potential Downside of Offering Discretion : With any type of managerial discretion, including in the realm of environmental management, there is the potential danger of managers opportunistically pushing their personal agendas at the expense of shareholders’ interests in profits (Shen & Cho, 2005). If this personal agenda is for the benefit of the environment, it can result in a positive contribution for sustainability.

And, it is not necessary to assume that discretionary actions related to corporate responsibility or sustainability need be at the expense of profits (Margolis & Walsh,

2003).

Formal Management Tools Coupled with Discretion : In order to ensure that the environmental policies are followed by all organizational members, including those not particularly committed to sustainability, a minimum level of control and

32

monitoring may be necessary. To this end, organizations can integrate sustainability criteria as part of formal performance assessments ensuring that all individuals are asked to make personal effort toward sustainability goals. This legitimizes environmental issues and can encourage more commitment and value-driven behavior in individual organizational members over time. There is nothing in the use of these formal management tools that negates the potential for an organization to also provide its managers with discretion related to environmental behavior.

(6) Employee Motivation : We propose that individual employee extrinsic

(compliance-based) motivation for sustainability can co-exist and positively influence more intrinsic (commitment-based) motivation over time. In this context it is important to note that, earlier psychology research claimed that control systems aimed at extrinsic motivation had the potential to undermine intrinsic motivation and Kunda and Schwartz (1983), amongst others, recommended avoiding control systems. But more recent evidence has shown how the two types of motivation can coexist and actually be mutually reinforcing (see Amabile et al.

, 1994).

Inrole and Extrarole Tasks: Businesses can establish management systems that emphasize both compliance and commitment-based approaches. When an organization uses control systems, it signals that it wants to foster a movement toward sustainability and demands that employees consider environmental issues as part of their inrole tasks. On the other hand, when an organization uses value-based orientations it signals that employees’ values and personal initiatives are important to the organization and that the organization welcomes voluntary contributions and extrarole tasks aimed at innovating and improving in the domain of sustainability.

(See Ramus and Killmer, in press, for more on extrarole environmental motivation.)

33

For example, when the organization insists on employee compliance to a sustainability policy, employees receive a clear message of the organization’s commitment to the policy (Ramus & Steger, 2000). Over time, and via daily environmentally responsible behavior, they might internalize this commitment. As

Maignan and Ferrell (2004) emphasized, when an issue becomes legitimate, it can influence identity over time ( doing can become being ; see also Whetten & Mackey,

2002). Based on this dynamic interaction between identity and behavior, the organization can encourage increasing levels of employee commitment to sustainability. We can see this as a correlate, at the individual level, of the development Post and Altman (1992) witness at the corporate level: a progressive increase in our society of voluntary and proactive approaches to sustainability.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation as Mutually Reinforcing: Employee participation, as noted above in the discussion of learning organization tools, is a useful element for mutually reinforcing intrinsic and extrinsic motivation .

As theorized by Kaplan

(2000) and demonstrated by Seguin, Pelletier, and Hunsley (1999) as well as Green-

Demers, Pelletier, and Menard (1997), active participation in proposing new solutions to environmental problems is a powerful way of increasing autonomous and intrinsically motivated environmentally responsible behavior. In asking employees to come up with ideas and solutions to environmental problems, they feel involved and important to the corporate greening process (Kaplan, 2000). In this way, organizations can gain employee commitment, encourage their environmental values to grow, and gradually make environmental efforts autonomous and voluntary (Seguin et al., 1999;

Green-Demers et al.

, 1997).

Thus, we propose that organizations can create a dynamic process that reinforces commitment to sustainability, 1) by encouraging environmental values be

34

acted upon by managers who care about sustainability (providing managerial discretion) and 2) by using both control systems and value-based orientations to feed into extrinsic and intrinsic employee motivation. As the commitment increases at the managerial and employee level, this might trigger a dialogue or communication process in which top-down communication is combined with bottom-up idea generation. Although compliance tools are still used, shared values in the company

(Ramus, 2005; see also Chatman, 1991) form the basis for an integrative framework in order to harmonize behavior in relation to sustainability. And there is reason to believe from Weaver and colleagues’ (1999a) empirical evidence that integrative systems that include both compliance- and value-based approaches are additive , rather than mutually exclusive.

DISCUSSION

We have asserted that different organizations can be expected to take different approaches to managing environmental issues. Here we will briefly discuss how two different hypothetical organizations, one on each extreme of the continuum, might take different paths in the dynamic model to move toward the center. Then we will discuss how the model helps demonstrate a more nuanced view of corporate greening.

Example One: Compliance-based Approach

One can imagine a company that fits firmly in the left-hand column of model two on all the mechanisms described. It is reactive to external pressures, sets its strategy to address these pressures as if they are threats to its license to operate, uses primarily formal, control-based tools, providing little or no managerial discretion related to environmental management, and sets goals for employees that extrinsically motivate them to take action against the external threat. This organization

35

may typically be focusing on profit maximization, believing that no action to protect the natural environment is a legitimate use of company resources unless it is instrumental in addressing a threat to its license to operate.

Through the process of addressing institutional pressures, Hoffman (2001) and other institutional theorist might say that the organization, overtime, could potentially shift from a cognitive framing of the issue as something they are coerced into addressing (regulative/ coercive) to something they believe they should do

(normative) (see Ramus & Montiel, 2005 for a further discussion of this dynamic).

Typically this shift might take place through what Maignan and Ferrell (2004) called an adjustment of organizational norms, which can potentially result in increased internal commitment (triggering actions from shared values – line 1), new modes of responsiveness (tending away from reactive and toward proactive – line 2), and new strategic framings (tending away from thinking of environmental issues as threats and a waste of organizational resources, toward seeing them as opportunities, and eventually, maybe, toward seeing them as profit-creating through integration – line 3.)

Once the organizational norms surrounding environmental management begin to shift, then the management tools (line 4) might also shift. For example, the organization when it stops seeing the environmental issues as threats and starts seeing potential positive outcomes from addressing them proactively and integrating them into their business, may then see advantages to encouraging more managerial discretion (line 5) and greater opportunities for employees to act on their own intrinsic motivation (line 6). The company’s management may begin to see value-based orientations as the only means for the organization to achieve the potential up-side from their environmental management efforts. Through the process of acting on the basis of the formal rewards and incentives to meet goals related to solving

36

environmental problems (i.e. reacting to external stakeholder pressures) individuals in the company may like applying their creative energy to this type of problem, see the benefits and begin to value the natural environment for its own sake. Thus not only the organizational norms can potentially shift, but the potential for bottom up pressure from individuals can potentially reinforce norms of commitment, and reinforce the shift toward the right-hand column of model two.

Example Two: Commitment-based Approach

On the other hand, one can imagine a company that fits firmly in the righthand column of model two on all the mechanisms described. It is driven by shared individual and organizational values of protecting the natural environment , responds voluntarily not needing external impetus to encourage it to promote sustainability, integrates environmental considerations into its business strategy, uses primarily informal, value-based management tools, provides substantial managerial discretion, and encourages employees to act on their own volition to promote sustainability within the company. This organization would typically be focused on the normative basis for environmental sustainability, believing that protecting the natural environment is a good in itself, independently of any instrumental benefits derived (e.g. profits, worker motivation, improved reputation).

In this case there is no need for institutional pressures to trigger organizational responses. The organizational norms carry the process forward. But there is a risk attached to having policy commitment without formal management tools to implement the policy, according to Winn and Angell (2000). If there is a tendency towards vision without action, talk of values without realistic goals, then the implementation process risks ineffectiveness. Therefore, an organization of this type that has a strong normative commitment to environmental sustainability might benefit

37

from using some of the mechanisms described under the compliance-based approach column of model two. For example, this company might achieve more effective implementation of environmental considerations into its business if it adopted control systems such as establishing policies and setting goals, measuring individual and organizational performance against these goals, evaluating what works and doesn’t work in the environmental program, and rewarding creative ideas and good environmental performance. In other terms, the adoption of such management tools reinforces and gives order to the environmental norms of the organization as well as to the aspirations of its members.

Nuanced Corporate Greening

An element of the systemic and organic nature of the sustainability process that has been virtually absent from research up to now is the multiple, complex, organization-specific paths of corporate greening (Winn & Angell, 2000).

Organizations who wish to move toward sustainability need to address the full range of organizational change necessary to develop more “green” corporate cultures over time (Post & Altman, 1992). In effect, our model of balanced continuums allows a more nuanced conceptualization of the myriad paths organizations can take to sustainability.

In other terms, the integration of commitment- and compliance-based approaches will necessarily be done differentially from firm to firm, depending on its specific characteristics, history, organizational culture, industry and cultural context, motivation, goals, etc. Some may focus on acting on organizational norms of commitment but be less focused on control systems. Others may have a lot of top management commitment but low employee concern, and these organizations may focus on using formal management tools to implement sustainability policy. Others

38

may have lower levels of top management concern, focusing on implementing policies that promote compliance with institutional pressures and demands. Some may have a strong focus on innovation and pro-activity, and establish management systems specifically aimed at product innovation. Yet others may rely on informal management tools that encourage employees’ commitment, allowing bottom-up pressure to promote the process through which sustainability grows. There is no single path to sustainability. But we argue the better an organization is at adopting a more complex path which embraces more elements from both compliance and commitment-based approaches, the more effective their corporate greening systems can potentially be for moving the organization toward environmental sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

“ Whereas what might be termed static patterns of value separate the economic, ethical, and ecological, dynamic patterns are integrative” (Bennis, Parikh, & Lessem, 1994: preface to

2 nd

edition).

“…the study of sustainability must shift from objective to subjective, from exterior nuts and bolts to interior hearts and minds” (Gladwin & Kennelly , 1995).

In this paper, we have argued that companies wishing to move toward sustainability may find it advantageous to accept the paradox inherent in using both compliance- and commitment-based approaches. We have shown that these two types of approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive but rather are potentially mutually reinforcing. Our theory intends to move scholars beyond arguments that juxtapose instrumental and normative justifications for sustainability, and instead to foster “both” “and” thinking. Many organizations which embrace both control and value-based orientations have demonstrated the compatibility of existing with this paradox ( Interface, 7 th

Generation, etc.). Our theory conceptualizes the multiple paths

39

to corporate greening, showing how both formal and informal management tools can create dynamics that encourage movement toward sustainability.

REFERENCES

Adler, P. S. & Borys, B. Two Types of Bureaucracy: Enabling and Coercive.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 1996, 41, 61-89.

Amabile, T. M. Motivating Creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review , 1997, 40, 39-58.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal , 1996, 39, 1154-1184.

Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., & Tighe, E. M. The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology , 1994, 66, 950-967.

Aquino, K. & Reed II, A. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology , 2002, 83, 1423-1440.

Aragòn-Correa, J.A., Fernando, M.R., Senise-Barrio, M.E. Managerial discretion and corporate commitment to the natural environment. Journal of Business Research ,

2004, 57, 964-975.

Argyris, C. & Schon, D. Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective .

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1978.

Bansal, P. From issues to actions: the importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organization

Science, 2003, 14, 510-27.

Bennis, W., Parikh, J., & Lessem, R. (Eds.) Beyond leadership: Balancing economics, ethics and ecology (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell,1994.

Brown, L. Plan B: Rescuing a planet under stress and a civilization in trouble . New

York, London: WW Norton & Co., 2003.

Carpenter, M.A. & Golden, B.R. Perceived managerial discretion: A study of cause and effect. Strategic Management Journal, 1997, 18, 187-206.

Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance.

Academy of Management Review , 1979, 4, 497-505.

Chatman, J. A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of personorganization fit. Academy of Management Review , 1989, 14, 333-350.

Chatman, J. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly , 1991, 39, 459-484.

40

Cordano, M. & Frieze, I. H. Pollution reduction preferences of U.S. environmental managers: Applying Ajzen's theory of planned behavior. Academy of Management

Journal , 2000, 43, 627-641.

Crane, A. Corporate greening as amoralization. Organization Studies, 2000, 21, 673-

696.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1987, 53, 1024-1037.

Dutton, J.E. & Dukerich, J.M. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal, 1991, 34, 517-554.

Egri, C.P. & Hornal, R.C. Strategic environmental human resource management and organizational performance: An exploratory study of the Canadian manufacturing sector. In S. Sharma & M. Starik (Eds.) Research in corporate sustainability (pp. 205-

236).

Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2002.

Epstein, M. J. Measuring corporate environmental performance: Best practices for costing and managing an effective environmental strategy.

Chicago, London: Irwin,

1996.

The environmental two step: Looking forward, moving backward.

New York: Times

Mirror, 1995.

Etzioni, A. A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations . New York: Free

Press, 1961.

Fayol, H. Administration industrielle et générale. Bulletin de la Societe de l’Industrie

Minerale , 1916, 10, 5-162.

Ferris, W. P. & Fanelli, A. R. The learning manager and the innerside of management.

In S. Cavaleri & D. Fearon (Eds.), Managing in Organizations that Learn (pp. 66-96).

Oxford: Blackwell Business, 1996.

Finkelstein, S. & Hambrick, D.C. Top-management team tenure and organizational outcomes: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 1990, 35, 484-503.

Fischer, K. & Schot, J. Environmental strategies for industry: International perspectives on research needs and policy implications.

Washington, D. C.: Island

Press, 1993.

Garvin, D. A. Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review , 1993, 71,