Agreement: ability to recognize correct sentences, avoiding errors in

advertisement

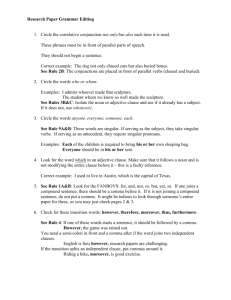

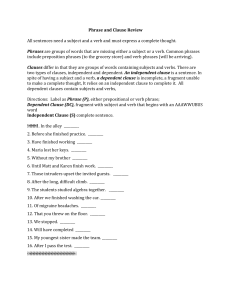

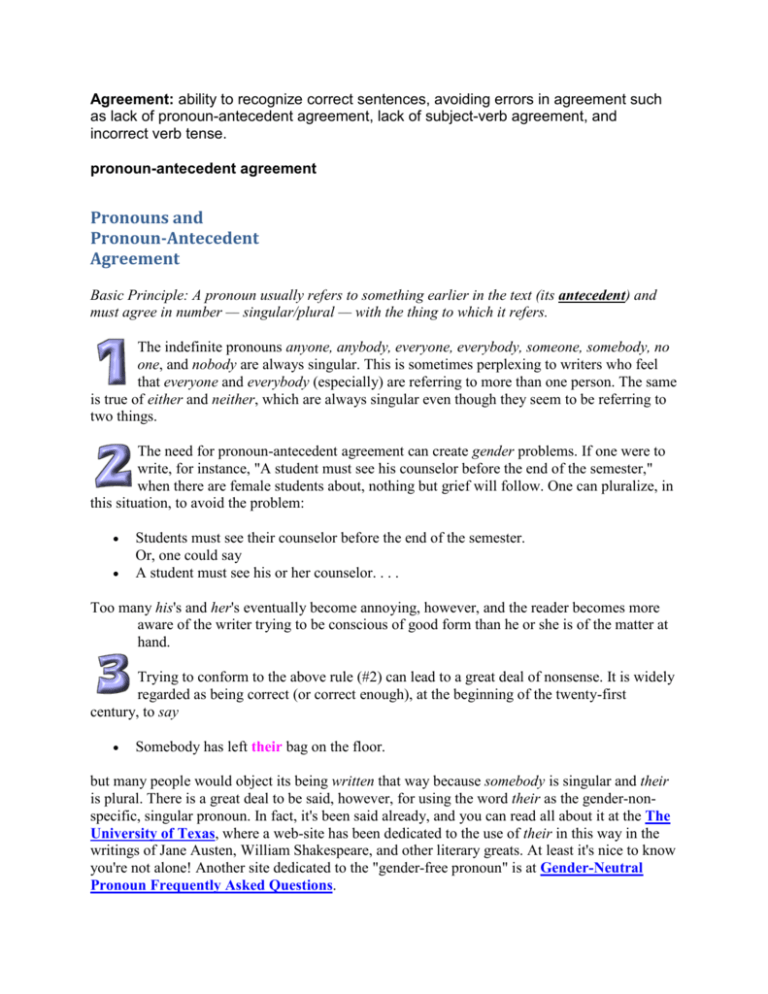

Agreement: ability to recognize correct sentences, avoiding errors in agreement such as lack of pronoun-antecedent agreement, lack of subject-verb agreement, and incorrect verb tense. pronoun-antecedent agreement Pronouns and Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement Basic Principle: A pronoun usually refers to something earlier in the text (its antecedent) and must agree in number — singular/plural — with the thing to which it refers. The indefinite pronouns anyone, anybody, everyone, everybody, someone, somebody, no one, and nobody are always singular. This is sometimes perplexing to writers who feel that everyone and everybody (especially) are referring to more than one person. The same is true of either and neither, which are always singular even though they seem to be referring to two things. The need for pronoun-antecedent agreement can create gender problems. If one were to write, for instance, "A student must see his counselor before the end of the semester," when there are female students about, nothing but grief will follow. One can pluralize, in this situation, to avoid the problem: • • Students must see their counselor before the end of the semester. Or, one could say A student must see his or her counselor. . . . Too many his's and her's eventually become annoying, however, and the reader becomes more aware of the writer trying to be conscious of good form than he or she is of the matter at hand. Trying to conform to the above rule (#2) can lead to a great deal of nonsense. It is widely regarded as being correct (or correct enough), at the beginning of the twenty-first century, to say • Somebody has left their bag on the floor. but many people would object its being written that way because somebody is singular and their is plural. There is a great deal to be said, however, for using the word their as the gender-nonspecific, singular pronoun. In fact, it's been said already, and you can read all about it at the The University of Texas, where a web-site has been dedicated to the use of their in this way in the writings of Jane Austen, William Shakespeare, and other literary greats. At least it's nice to know you're not alone! Another site dedicated to the "gender-free pronoun" is at Gender-Neutral Pronoun Frequently Asked Questions. Remember that when we compound a pronoun with something else, we don't want to change its form. Following this rule carefully often creates something that "doesn't sound good." You would write, "This money is for me," so when someone else becomes involved, don't write, "This money is for Fred and I." Try these: • • This money is for him and me. This arrangement is between Fred and him. Those are both good sentences. One of the most frequently asked questions about grammar is about choosing between the various forms of the pronoun who: who, whose, whom, whoever, whomever. The number (singular or plural) of the pronoun (and its accompanying verbs) is determined by what the pronoun refers to; it can refer to a singular person or a group of people: • • The person who hit my car should have to pay to fix the damages. The people who have been standing in line the longest should get in first. It might be useful to compare the forms of who to the forms of the pronouns he and they. Their forms are similar: Subject Form Possessive Form Object Form Singular he who his whose him whom Plural they who their whose them whom To choose correctly among the forms of who, re-phrase the sentence so you choose between he and him. If you want him, write whom; if you want he, write who. • • • • • Who do you think is responsible? (Do you think he is responsible?) Whom shall we ask to the party? (Shall we ask him to the party?) Give the box to whomever you please. (Give the box to him.) Give the box to whoever seems to want it most. (He seems to want it most. [And then the clause "whoever seems to want it most" is the object of the preposition "to."]) Whoever shows up first will win the prize. (He shows up first.) lack of subject-verb agreement Subject-Verb Agreement Basic Principle: Singular subjects need singular verbs; plural subjects need plural verbs. My brother is a nutritionist. My sisters are mathematicians. See the section on Plurals for additional help with subject-verb agreement. The indefinite pronouns anyone, everyone, someone, no one, nobody are always singular and, therefore, require singular verbs. • • Everyone has done his or her homework. Somebody has left her purse. Some indefinite pronouns — such as all, some — are singular or plural depending on what they're referring to. (Is the thing referred to countable or not?) Be careful choosing a verb to accompany such pronouns. • • Some of the beads are missing. Some of the water is gone. On the other hand, there is one indefinite pronoun, none, that can be either singular or plural; it often doesn't matter whether you use a singular or a plural verb — unless something else in the sentence determines its number. (Writers generally think of none as meaning not any and will choose a plural verb, as in "None of the engines are working," but when something else makes us regard none as meaning not one, we want a singular verb, as in "None of the food is fresh.") • • • None of you claims responsibility for this incident? None of you claim responsibility for this incident? None of the students have done their homework. (In this last example, the word their precludes the use of the singular verb. Some indefinite pronouns are particularly troublesome Everyone and everybody (listed above, also) certainly feel like more than one person and, therefore, students are sometimes tempted to use a plural verb with them. They are always singular, though. Each is often followed by a prepositional phrase ending in a plural word (Each of the cars), thus confusing the verb choice. Each, too, is always singular and requires a singular verb. Everyone has finished his or her homework. You would always say, "Everybody is here." This means that the word is singular and nothing will change that. Each of the students is responsible for doing his or her work in the library. Don't let the word "students" confuse you; the subject is each and each is always singular — Each is responsible. Phrases such as together with, as well as, and along with are not the same as and. The phrase introduced by as well as or along with will modify the earlier word (mayor in this case), but it does not compound the subjects (as the word and would do). • • The mayor as well as his brothers is going to prison. The mayor and his brothers are going to jail. The pronouns neither and either are singular and require singular verbs even though they seem to be referring, in a sense, to two things. • • Neither of the two traffic lights is working. Which shirt do you want for Christmas? Either is fine with me. In informal writing, neither and either sometimes take a plural verb when these pronouns are followed by a prepositional phrase beginning with of. This is particularly true of interrogative constructions: "Have either of you two clowns read the assignment?" "Are either of you taking this seriously?" Burchfield calls this "a clash between notional and actual agreement."* The conjunction or does not conjoin (as and does): when nor or or is used the subject closer to the verb determines the number of the verb. Whether the subject comes before or after the verb doesn't matter; the proximity determines the number. • • • • Either my father or my brothers are going to sell the house. Neither my brothers nor my father is going to sell the house. Are either my brothers or my father responsible? Is either my father or my brothers responsible? Because a sentence like "Neither my brothers nor my father is going to sell the house" sounds peculiar, it is probably a good idea to put the plural subject closer to the verb whenever that is possible. The words there and here are never subjects. • • • There are two reasons [plural subject] for this. There is no reason for this. Here are two apples. With these constructions (called expletive constructions), the subject follows the verb but still determines the number of the verb. Verbs in the present tense for third-person, singular subjects (he, she, it and anything those words can stand for) have s-endings. Other verbs do not add s-endings. He loves and she loves and they love_ and . . . . Sometimes modifiers will get betwen a subject and its verb, but these modifiers must not confuse the agreement between the subject and its verb. The mayor, who has been convicted along with his four brothers on four counts of various crimes but who also seems, like a cat, to have several political lives, is finally going to jail. Sometimes nouns take weird forms and can fool us into thinking they're plural when they're really singular and vice-versa. Consult the section on the Plural Forms of Nouns and the section on Collective Nouns for additional help. Words such as glasses, pants, pliers, and scissors are regarded as plural (and require plural verbs) unless they're preceded the phrase pair of (in which case the word pair becomes the subject). • • • My glasses were on the bed. My pants were torn. A pair of plaid trousers is in the closet. Some words end in -s and appear to be plural but are really singular and require singular verbs. • • The news from the front is bad. Measles is a dangerous disease for pregnant women. On the other hand, some words ending in -s refer to a single thing but are nonetheless plural and require a plural verb. • • • My assets were wiped out in the depression. The average worker's earnings have gone up dramatically. Our thanks go to the workers who supported the union. The names of sports teams that do not end in "s" will take a plural verb: the Miami Heat have been looking … , The Connecticut Sun are hoping that new talent … . See the section on plurals for help with this problem. Fractional expressions such as half of, a part of, a percentage of, a majority of are sometimes singular and sometimes plural, depending on the meaning. (The same is true, of course, when all, any, more, most and some act as subjects.) Sums and products of mathematical processes are expressed as singular and require singular verbs. The expression "more than one" (oddly enough) takes a singular verb: "More than one student has tried this." • • • • • • • • Some of the voters are still angry. A large percentage of the older population is voting against her. Two-fifths of the troops were lost in the battle. Two-fifths of the vineyard was destroyed by fire. Forty percent of the students are in favor of changing the policy. Forty percent of the student body is in favor of changing the policy. Two and two is four. Four times four divided by two is eight. If your sentence compounds a positive and a negative subject and one is plural, the other singular, the verb should agree with the positive subject. • • • The department members but not the chair have decided not to teach on Valentine's Day. It is not the faculty members but the president who decides this issue. It was the speaker, not his ideas, that has provoked the students to riot. incorrect verb tense. Sequence of Verb Tenses Although the various shades of time and sequence are usually conveyed adequately in informal speech and writing, especially by native speakers and writers, they can create havoc in academic writing and they sometimes are troublesome among students for whom English is a second language. This difficulty is especially evident in complex sentences when there is a difference between the time expressed in an independent clause and the time expressed in a dependent clause. Another difficulty arises with the use of infinitives and participles, modals which also convey a sense of time. We hope the tables below will provide the order necessary to help writers sort out tense sequences. As long as the main clause's verb is in neither the past nor the past perfect tense, the verb of the subordinate clause can be in any tense that conveys meaning accurately. When the main clause verb is in the past or past perfect, however, the verb in the subordinate clause must be in the past or past perfect. The exception to this rule is when the subordinate clause expresses what is commonly known as a general truth: • • • In the 1950s, English teachers still believed that a background in Latin is essential for an understanding of English. Columbus somehow knew that the world is round. Slaveowners widely understood that literacy among oppressed people is a dangerous thing. The tables below demonstrate the correct relationship of tenses between clauses where time is of the essence (i.e., within sentences used to convey ideas about actions or conditions that take place over time). Click HERE for a table describing the various tenses of the active voice. Click HERE for a table describing tense sequences of infinitives and participles. Tense in Purpose of Dependent Independent Clause/ Clause Tense in Dependent Clause Simple Present Example(s) To show same-time action, use the present tense I am eager to go to the concert because I love the Wallflowers. To show earlier action, use past I know that I made the right choice. tense To show a period of time extending from some point in the past to the They believe that they have elected present, use the present perfect the right candidate. tense. Simple Past To show action to come, use the future tense. The President says that he will veto the bill. To show another completed past action, use the past tense. I wanted to go home because I missed my parents. To show an earlier action, use the past perfect tense. She knew she had made the right choice. To state a general truth, use the present tense. The Deists believed that the universe is like a giant clock. For any purpose, use the past tense. She has grown a foot since she turned nine. The crowd had turned nasty before the sheriff returned. To show action happening at the same time, use the present tense. I will be so happy if they fix my car today. To show an earlier action, use the past tense. You will surely pass this exam if you studied hard. To show future action earlier than the action of the independent clause, use the present perfect tense. The college will probably close its doors next summer if enrollments have not increased. For any purpose, use the present tense or present perfect tense. Most students will have taken sixty credits by the time they graduate. Most students will have taken sixty Present Perfect or Past Perfect Future Future Perfect credits by the time they have graduated. Authority for this section: Quick Access: Reference for Writers by Lynn Quitman Troyka. Simon & Schuster: New York. 1995. Used with permission. Examples and format our own. Note: Unless logic dictates otherwise, when discussing a work of literature, use the present tense: "Robert Frost describes the action of snow on the birch trees." "This line suggests the burden of the ice." "The use of the present tense in Carver's stories creates a sense of immediacy." Sequence of Tenses With Infinitives and Participles Like verbs, infinitives and participles are capable of conveying the idea of action in time; therefore, it is important that we observe the appropriate tense sequence when using these modals. INFINITIVES Tense of Infinitive Present Infinitive (to see) Perfect Infinitive (to have seen) Role of Infinitive To show same-time action or action later than the verb To show action earlier than the verb Example(s) Coach Espinoza is eager to try out her new drills. [The eagerness is now; the trying out will happen later.] She would have liked to see more veterans returning. [The present infinitive to see is in the same time as the past would have liked.] The fans would like to have seen some improvement this year. ["Would like" describes a present condition; "to have seen" describes something prior to that time.] They consider the team to have been coached very well. [The perfect infinitive to have been coached indicates a time prior to the verb consider.] PARTICIPLES Tense of Participle Present Participl e (seeing) Role of Participle Example(s) To show action occurring at the same time as that of the verb Working on the fundamentals, the team slowly began to improve. [The action expressed by began happened in the past, at the same time the working happened.] Prepared by last year's experience, the coach knows not to expect too much. [The action expressed by knows is in the present; prepared expresses a time prior to that time.] Past Participl e or Present Perfect Participl e To show action occurring earlier than that of the verb Having experimented with several game plans, the coaching staff devised a master strategy. [The present perfect participle having experimented indicates a time prior to the past tense verb, devised.] Modifiers: ability to recognize correct sentences, avoiding errors in modification such as misplaced modifiers and dangling modifiers. misplaced modifiers and dangling modifiers Modifier Placement Basic Principle: Modifiers are like teenagers: they fall in love with whatever they're next to. Make sure they're next to something they ought to modify! MISPLACED MODIFIER: Some modifiers, especially simple modifiers — only, just, nearly, barely — have a bad habit of slipping into the wrong place in a sentence. (In the sentence below, what does it mean to "barely kick" something?) Confusion He barely kicked that ball twenty yards. Repair Work He kicked that ball barely twenty yards. The issue of the proper placement of "only" has long been argued among grammarians. Many careful writers will insist that "only" be placed immediately before the word or phrase it modifies. Thus "I only gave him three dollars" would be rewritten as "I gave him only three dollars." Some grammarians, however, have argued that such precision is not really necessary, that there is no danger of misreading "I only gave him three dollars" and that "only" can safely and naturally be placed between the subject and the verb. The argument has been going on for two hundred years. DANGLING MODIFIER: When we begin a sentence with a modifying word, phrase, or clause, we must make sure the next thing that comes along can, in fact, be modified by that modifier. When a modifier improperly modifies something, it is called a "dangling modifier." This often happens with beginning participial phrases, making "dangling participles" an all too common phenomenon. In the sentence below, we can't have a car changing its own oil. Confusion Changing the oil every 3,000 miles, the car seemed to run better. Repair Work Changing the oil every 3,000 miles, Fred found he could get much better gas mileage. A participial phrase followed by an Expletive Construction will often be a dangling participle — but the expletive construction is probably not a good idea anyway. This faulty sentence can be remedied by changing the participial phrase into a full-fledged clause with a subject and verb. Changing the oil every 3,000 miles, there is an easy way to keep your car running smoothly. Repair Work If we change the oil every 3,000 miles, we can keep our car running smoothly. Confusion A participial phrase followed by a Passive Verb is also apt to be a dangler because the real actor of the sentence will be disguised. Confusion Changing the oil every 3,000 miles, the car was kept in excellent condition. Repair Work Changing the oil every 3,000 miles, we kept the car in excellent condition. An infinitive phrase can also "dangle." The infinitive phrase below should probably modify the person(s) who set up the exercise program. To keep the young recruits interested in getting in shape, an exercise program was set up for the summer months. Repair Work To keep the young recruits interested in getting in shape, the coaching staff set up an exercise program for the summer months. Confusion SQUINTING MODIFIER: A third problem in modifier placement is described as a "squinting modifier." This is an unfortunate result of an adverb's ability to pop up almost anywhere in a sentence; structurally, the adverb may function fine, but its meaning can be obscure or ambiguous. For instance, in the sentence below, do the students seek advice frequently or can they frequently improve their grades by seeking advice? You can't tell from that sentence because the adverb often is "squinting" (you can't tell which way it's looking). Let's try placing the adverb elsewhere. Confusion Students who seek their instructors' advice often can improve their grades. Repair Work Student who often seek their instructors' advice can improve their grades. Repair Work Students who seek their instructors' advice can often improve their grades. Diction/Logic: ability to recognize correct sentences in written English, avoiding errors in diction and logic such as inappropriate conjunctions that create illogical sentences. inappropriate conjunctions that create illogical sentences Conjunctions Definition Some words are satisfied spending an evening at home, alone, eating ice-cream right out of the box, watching Seinfeld re-runs on TV, or reading a good book. Others aren't happy unless they're out on the town, mixing it up with other words; they're joiners and they just can't help themselves. A conjunction is a joiner, a word that connects (conjoins) parts of a sentence. Coordinating Conjunctions The simple, little conjunctions are called coordinating conjunctions (you can click on the words to see specific descriptions of each one): Coordinating Conjunctions and but or yet for nor so (It may help you remember these conjunctions by recalling that they all have fewer than four letters. Also, remember the acronym FANBOYS: For-And-Nor-But-Or-Yet-So. Be careful of the words then and now; neither is a coordinating conjunction, so what we say about coordinating conjunctions' roles in a sentence and punctuation does not apply to those two words.) When a coordinating conjunction connects two independent clauses, it is often (but not always) accompanied by a comma: • Ulysses wants to play for UConn, but he has had trouble meeting the academic requirements. When the two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction are nicely balanced or brief, many writers will omit the comma: • Ulysses has a great jump shot but he isn't quick on his feet. The comma is always correct when used to separate two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction. See Punctuation Between Two Independent Clauses for further help. A comma is also correct when and is used to attach the last item of a serial list, although many writers (especially in newspapers) will omit that final comma: • Click on "Conjunction Junction" to read and hear Bob Dorough's "Conjunction Junction" (from Scholastic Rock, 1973). Schoolhouse Rock® and its characters and other elements are trademarks and service marks of American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. Used with permission. Ulysses spent his summer studying basic math, writing, and reading comprehension. When a coordinating conjunction is used to connect all the elements in a series, a comma is not used: • Presbyterians and Methodists and Baptists are the prevalent Protestant congregations in Oklahoma. A comma is also used with but when expressing a contrast: • This is a useful rule, but difficult to remember. In most of their other roles as joiners (other than joining independent clauses, that is), coordinating conjunctions can join two sentence elements without the help of a comma. • • • • Hemingway and Fitzgerald are among the American expatriates of the between-the-wars era. Hemingway was renowned for his clear style and his insights into American notions of male identity. It is hard to say whether Hemingway or Fitzgerald is the more interesting cultural icon of his day. Although Hemingway is sometimes disparaged for his unpleasant portrayal of women and for his glorification of machismo, we nonetheless find some sympathetic, even heroic, female figures in his novels and short stories. Beginning a Sentence with And or But A frequently asked question about conjunctions is whether and or but can be used at the beginning of a sentence. This is what R.W. Burchfield has to say about this use of and: There is a persistent belief that it is improper to begin a sentence with And, but this prohibition has been cheerfully ignored by standard authors from AngloSaxon times onwards. An initial And is a useful aid to writers as the narrative continues. from The New Fowler's Modern English Usage edited by R.W. Burchfield. Clarendon Press: Oxford, England. 1996. Used with the permission of Oxford University Press. The same is true with the conjunction but. A sentence beginning with and or but will tend to draw attention to itself and its transitional function. Writers should examine such sentences with two questions in mind: (1) would the sentence and paragraph function just as well without the initial conjunction? (2) should the sentence in question be connected to the previous sentence? If the initial conjunction still seems appropriate, use it. Among the coordinating conjunctions, the most common, of course, are and, but, and or. It might be helpful to explore the uses of these three little words. The examples below by no means exhaust the possible meanings of these conjunctions. AN D a. To suggest that one idea is chronologically sequential to another: "Tashonda sent in her applications and waited by the phone for a response." b. To suggest that one idea is the result of another: "Willie heard the weather report and promptly boarded up his house." c. To suggest that one idea is in contrast to another (frequently replaced by but in this usage): "Juanita is brilliant and Shalimar has a pleasant personality. d. To suggest an element of surprise (sometimes replaced by yet in this usage): "Hartford is a rich city and suffers from many symptoms of urban blight." e. To suggest that one clause is dependent upon another, conditionally (usually the first clause is an imperative): "Use your credit cards frequently and you'll soon find yourself deep in debt." f. To suggest a kind of "comment" on the first clause: "Charlie became addicted to gambling — and that surprised no one who knew him." BUT a. To suggest a contrast that is unexpected in light of the first clause: "Joey lost a fortune in the stock market, but he still seems able to live quite comfortably." b. To suggest in an affirmative sense what the first part of the sentence implied in a negative way (sometimes replaced by on the contrary): "The club never invested foolishly, but used the services of a sage investment counselor." c. To connect two ideas with the meaning of "with the exception of" (and then the second word takes over as subject): "Everybody but Goldenbreath is trying out for the team." OR a. To suggest that only one possibility can be realized, excluding one or the other: "You can study hard for this exam or you can fail." b. To suggest the inclusive combination of alternatives: "We can broil chicken on the grill tonight, or we can just eat leftovers. c. To suggest a refinement of the first clause: "Smith College is the premier all-women's college in the country, or so it seems to most Smith College alumnae." d. To suggest a restatement or "correction" of the first part of the sentence: "There are no rattlesnakes in this canyon, or so our guide tells us." e. To suggest a negative condition: "The New Hampshire state motto is the rather grim "Live free or die." f. To suggest a negative alternative without the use of an imperative (see use of and above): "They must approve his political style or they wouldn't keep electing him mayor." Authority used for this section on the uses of and, but, and or: A University Grammar of English by Randolph Quirk and Sidney Greenbaum. Longman Group: Essex, England. 1993. Used with permission. Examples our own. The Others . . . The conjunction NOR is not extinct, but it is not used nearly as often as the other conjunctions, so it might feel a bit odd when nor does come up in conversation or writing. Its most common use is as the little brother in the correlative pair, neither-nor (see below): • • He is neither sane nor brilliant. That is neither what I said nor what I meant. >It can be used with other negative expressions: • That is not what I meant to say, nor should you interpret my statement as an admission of guilt. It is possible to use nor without a preceding negative element, but it is unusual and, to an extent, rather stuffy: • George's handshake is as good as any written contract, nor has he ever proven untrustworthy. The word YET functions sometimes as an adverb and has several meanings: in addition ("yet another cause of trouble" or "a simple yet noble woman"), even ("yet more expensive"), still ("he is yet a novice"), eventually ("they may yet win"), and so soon as now ("he's not here yet"). It also functions as a coordinating conjunction meaning something like "nevertheless" or "but." The word yet seems to carry an element of distinctiveness that but can seldom register. • • John plays basketball well, yet his favorite sport is badminton. The visitors complained loudly about the heat, yet they continued to play golf every day. In sentences such as the second one, above, the pronoun subject of the second clause ("they," in this case) is often left out. When that happens, the comma preceding the conjunction might also disappear: "The visitors complained loudly yet continued to play golf every day." Yet is sometimes combined with other conjunctions, but or and. It would not be unusual to see and yet in sentences like the ones above. This usage is acceptable. The word FOR is most often used as a preposition, of course, but it does serve, on rare occasions, as a coordinating conjunction. Some people regard the conjunction for as rather highfalutin and literary, and it does tend to add a bit of weightiness to the text. Beginning a sentence with the conjunction "for" is probably not a good idea, except when you're singing "For he's a jolly good fellow. "For" has serious sequential implications and in its use the order of thoughts is more important than it is, say, with because or since. Its function is to introduce the reason for the preceding clause: • • John thought he had a good chance to get the job, for his father was on the company's board of trustees. Most of the visitors were happy just sitting around in the shade, for it had been a long, dusty journey on the train. Be careful of the conjunction SO. Sometimes it can connect two independent clauses along with a comma, but sometimes it can't. For instance, in this sentence, • Soto is not the only Olympic athlete in his family, so are his brother, sister, and his Uncle Chet. where the word so means "as well" or "in addition," most careful writers would use a semicolon between the two independent clauses. In the following sentence, where so is acting like a minorleague "therefore," the conjunction and the comma are adequate to the task: • Soto has always been nervous in large gatherings, so it is no surprise that he avoids crowds of his adoring fans. Sometimes, at the beginning of a sentence, so will act as a kind of summing up device or transition, and when it does, it is often set off from the rest of the sentence with a comma: • So, the sheriff peremptorily removed the child from the custody of his parents. The Case of Then and Than In some parts of the United States, we are told, then and than not only look alike, they sound alike. Like a teacher with twins in her classroom, you need to be able to distinguish between these two words; otherwise, they'll become mischievous. They are often used and they should be used for the right purposes. Than is used to make comparisons. In the sentence "Piggy would rather be rescued then stay on the island," we have employed the wrong word because a comparison is being made between Piggy's two choices; we need than instead. In the sentence, "Other than Pincher Martin, Golding did not write another popular novel," the adverbial construction "other than" helps us make an implied comparison; this usage is perfectly acceptable in the United States but careful writers in the UK try to avoid it (Burchfield). Generally, the only question about than arises when we have to decide whether the word is being used as a conjunction or as a preposition. If it's a preposition (and Merriam-Webster's dictionary provides for this usage), then the word that follows it should be in the object form. • • He's taller and somewhat more handsome than me. Just because you look like him doesn't mean you can play better than him. Most careful writers, however, will insist that than be used as a conjunction; it's as if part of the clause introduced by than has been left out: • • He's taller and somewhat more handsome than I [am handsome]. You can play better than he [can play]. In formal, academic text, you should probably use than as a conjunction and follow it with the subject form of a pronoun (where a pronoun is appropriate). Then is a conjunction, but it is not one of the little conjunctions listed at the top of this page. We can use the FANBOYS conjunctions to connect two independent clauses; usually, they will be accompanied (preceded) by a comma. Too many students think that then works the same way: "Caesar invaded Gaul, then he turned his attention to England." You can tell the difference between then and a coordinating conjunction by trying to move the word around in the sentence. We can write "he then turned his attention to England"; "he turned his attention, then, to England"; he turned his attention to England then." The word can move around within the clause. Try that with a conjunction, and you will quickly see that the conjunction cannot move around. "Caesar invaded Gaul, and then he turned his attention to England." The word and is stuck exactly there and cannot move like then, which is more like an adverbial conjunction (or conjunctive adverb — see below) than a coordinating conjunction. Our original sentence in this paragraph — "Caesar invaded Gaul, then he turned his attention to England" — is a comma splice, a faulty sentence construction in which a comma tries to hold together two independent clauses all by itself: the comma needs a coordinating conjunction to help out, and the word then simply doesn't work that way. Subordinating Conjunctions A Subordinating Conjunction (sometimes called a dependent word or subordinator) comes at the beginning of a Subordinate (or Dependent) Clause and establishes the relationship between the dependent clause and the rest of the sentence. It also turns the clause into something that depends on the rest of the sentence for its meaning. • • • He took to the stage as though he had been preparing for this moment all his life. Because he loved acting, he refused to give up his dream of being in the movies. Unless we act now, all is lost. Notice that some of the subordinating conjunctions in the table below — after, before, since — are also prepositions, but as subordinators they are being used to introduce a clause and to subordinate the following clause to the independent element in the sentence. Common Subordinating Conjunctions after although as as if as long as as though because before even if even though if if only in order that now that once rather than since so that than that though till unless until when whenever where whereas wherever while The Case of Like and As Strictly speaking, the word like is a preposition, not a conjunction. It can, therefore, be used to introduce a prepositional phrase ("My brother is tall like my father"), but it should not be used to introduce a clause ("My brother can't play the piano like as he did before the accident" or "It looks like as if basketball is quickly overtaking baseball as America's national sport."). To introduce a clause, it's a good idea to use as, as though, or as if, instead. • • • Like As I told you earlier, the lecture has been postponed. It looks like as if it's going to snow this afternoon. Johnson kept looking out the window like as though he had someone waiting for him. In formal, academic text, it's a good idea to reserve the use of like for situations in which similarities are being pointed out: • This community college is like a two-year liberal arts college. However, when you are listing things that have similarities, such as is probably more suitable: • The college has several highly regarded neighbors, like such as the Mark Twain House, St. Francis Hospital, the Connecticut Historical Society, and the UConn Law School. Omitting That The word that is used as a conjunction to connect a subordinate clause to a preceding verb. In this construction that is sometimes called the "expletive that." Indeed, the word is often omitted to good effect, but the very fact of easy omission causes some editors to take out the red pen and strike out the conjunction that wherever it appears. In the following sentences, we can happily omit the that (or keep it, depending on how the sentence sounds to us): • • • Isabel knew [that] she was about to be fired. She definitely felt [that] her fellow employees hadn't supported her. I hope [that] she doesn't blame me. Sometimes omitting the that creates a break in the flow of a sentence, a break that can be adequately bridged with the use of a comma: • • The problem is, that production in her department has dropped. Remember, that we didn't have these problems before she started working here. As a general rule, if the sentence feels just as good without the that, if no ambiguity results from its omission, if the sentence is more efficient or elegant without it, then we can safely omit the that. Theodore Bernstein lists three conditions in which we should maintain the conjunction that: • • • When a time element intervenes between the verb and the clause: "The boss said yesterday that production in this department was down fifty percent." (Notice the position of "yesterday.") When the verb of the clause is long delayed: "Our annual report revealed that some losses sustained by this department in the third quarter of last year were worse than previously thought." (Notice the distance between the subject "losses" and its verb, "were.") When a second that can clear up who said or did what: "The CEO said that Isabel's department was slacking off and that production dropped precipitously in the fourth quarter." (Did the CEO say that production dropped or was the drop a result of what he said about Isabel's department? The second that makes the sentence clear.) Authority for this section: Dos, Don'ts & Maybes of English Usage by Theodore Bernstein. Gramercy Books: New York. 1999. p. 217. Examples our own. Beginning a Sentence with Because Somehow, the notion that one should not begin a sentence with the subordinating conjunction because retains a mysterious grip on people's sense of writing proprieties. This might come about because a sentence that begins with because could well end up a fragment if one is not careful to follow up the "because clause" with an independent clause. • Because e-mail now plays such a huge role in our communications industry. When the "because clause" is properly subordinated to another idea (regardless of the position of the clause in the sentence), there is absolutely nothing wrong with it: • Because e-mail now plays such a huge role in our communications industry, the postal service would very much like to see it taxed in some manner. Correlative Conjunctions Some conjunctions combine with other words to form what are called correlative conjunctions. They always travel in pairs, joining various sentence elements that should be treated as grammatically equal. • • • She led the team not only in statistics but also by virtue of her enthusiasm. Polonius said, "Neither a borrower nor a lender be." Whether you win this race or lose it doesn't matter as long as you do your best. Correlative conjunctions sometimes create problems in parallel form. Click HERE for help with those problems. Here is a brief list of common correlative conjunctions. both . . . and not only . . . but also not . . . but either . . . or neither . . . nor whether . . . or as . . . as Conjunctive Adverbs The conjunctive adverbs such as however, moreover, nevertheless, consequently, as a result are used to create complex relationships between ideas. Refer to the section on Coherence: Transitions Between Ideas for an extensive list of conjunctive adverbs categorized according to their various uses and for some advice on their application within sentences (including punctuation issues). Sentence Structure: ability to recognize correct sentences, avoiding errors in sentence structure such as sentence fragments, faulty subordination/coordination, and lack of parallelism. sentence fragments Sentence Fragments Definition A SENTENCE FRAGMENT fails to be a sentence in the sense that it cannot stand by itself. It does not contain even one independent clause. There are several reasons why a group of words may seem to act like a sentence but not have the wherewithal to make it as a complete thought. It may locate something in time and place with a prepositional phrase or a series of such phrases, but it's still lacking a proper subject-verb relationship within an independent clause: In Japan, during the last war and just before the armistice. This sentence accomplishes a great deal in terms of placing the reader in time and place, but there is no subject, no verb. It describes something, but there is no subject-verb relationship: Working far into the night in an effort to salvage her little boat. This is a verbal phrase that wants to modify something, the real subject of the sentence (about to come up), probably the she who was working so hard. It may have most of the makings of a sentence but still be missing an important part of a verb string: Some of the students working in Professor Espinoza's laboratory last semester. Remember that an -ing verb form without an auxiliary form to accompany it can never be a verb. It may even have a subject-verb relationship, but it has been subordinated to another idea by a dependent word and so cannot stand by itself: Even though he had the better arguments and was by far the more powerful speaker. This sentence fragment has a subject, he, and two verbs, had and was, but it cannot stand by itself because of the dependent word (subordinating conjunction) even though. We need an independent clause to follow up this dependent clause: . . . the more powerful speaker, he lost the case because he didn't understand the jury. • faulty subordination/coordination The Principles of Coordination and Subordination Introduction Coordination: linking together words, groups of words (clauses), or sentences of equal type and importance, to put energy into writing. Coordinating Conjunctions: and, or, nor, for, but, so, yet, either/or, and neither/nor. a. Two principles to keep in mind: By combining words and groups of words, you avoid repetition that steals energy from what you write; and b. By combining whole sentences, you reveal the relationships between the thoughts. Example: Over the past decade many African American students have chosen to complete their formal education at Southern colleges and now in the city of Atlanta there is a major educational center built expressly to accomodate this upsurge of interest in the New South. (Two main clauses are given equal emphasis and connected by the coordinating conjunction and ) Subordination: clearly empashizes which words, groups of words (clauses), or sentences are the most important in the writing. Subordinate Conjunctions: Takes into account five (5) factors -- (1) Time: when, after, as soon as, whenever, while, before; (2) Place: where, wherever; (3) Cause: because, since, in order that, so that; (4) Contrast/Concession: although, as if, though, while; and (5) Condition: if, unless, provided, since,as long as. Example: Because CSUN is located in the San Fernando Valley, the university has become very attractive to students living in the inner city who want to stay close to home and yet not face the pressures of city life. (Dependent clause introduced by the subordinating conjunction because; independent or main clause begins with the university) Caveat: One wants to avoid faulty or excessive coordination. Faulty coordination: gives equal emphasis to unequal or unrelated clauses. Example: The African American playwright August Wilson has won two Pulitzer Prizes for drama, and he now lives in Seattle, Washington. The clause he now lives in Seattle, Washington has little or no connection to The African American playwright August Wilson has won two Pulitzer Prizes for drama. Therefore, the clauses should not be coordinated. But you, writer, may want to include this information in the paragraph because it is interesting and perhaps even important, even though it does not pertain directly to the main idea of the paragraph. Placing he now lives in Seattle, Washington might detract from the paragraph's unity. We can revise faulty coordination by putting part of the sentence in a dependent clause, modifying phrase, or appositive phrase (an appositive is a noun or pronoun -- often with modifiers -- placed near another noun or pronoun to explain, describe, or identify it). 1. CSUN's Square, a hangout for its African American student community, has been quiet of late. (A hangout for its African American student community describes CSUN's Square); or 2. My sister Tiyifa lives in Colorado Springs. (Tiyifa identifies sister ) Typically, an appositive follows the word it refers to, but it may also precede the word: 1. A very inspirational tale of courage and honor, Glory is based on actual accounts of the all-black 54th Regiment during the American Civil War. (A very inspirational tale of courage and honor describes Glory) Resuming with means of correcting faulty or excessive coordination, we note the following examples: 1. The African American playwright August Wilson, who now lives in Seattle, Washington, has won two Pulitzer Prizes for drama. (Dependent Clause) 2. The African American playwright August Wilson, now Seattle-based, has won two Pultizer Prizes for drama (modifying phrase) 3. The African American August Wilson, a Seattle playwright, has won two Pulitzer Prizes for drama (An appositive phrase). We can go further by noting that when a single sentence contains more than one clause, the clauses may be given equal or unequal emphasis. Clauses given equal emphasis in one sentence are coordinate and should be connected by a cooordinating word or punctuation. Clauses given less emphasis in a sentence are dependent, or subordinate, and should be introduced by a subordinating word (conjunction). Rules to Remember Concerning Faulty Subordination: There are three (3) rules to keep in mind with respect to faulty or excessive subordination in writing: 1. Faulty subordination occurs when the more important clause is placed in a subordinate position in the sentence or when the expected relation between clauses is reversed. Example: Japanese-made cars are popular with American consumers although their import poses at least a short-term threat to the livelihood of some American workers (In an essay or composition about he problems of the American worker this sentence would take attention away from the worker and incorrectly emphasize Japanese-made cars.) 2. Correct faulty subordination by changing the position of the subordinating word or phrase; Example: Although Japanese-made cars are popular with American consumers, their import poses at least a short-term threat to the livelihood of some American workers. 3. Keep in mind that excessive subordination occurs when a sentence contains a series of cluses, each subordinate to an earlier one. To correct excessive subordination, break the sentence into two or more sentences or change some of the dependent clauses to modifying phrases or appositives. Example: LaTosha Robinson, who was a San Francisco-native who lived in the University Park Apartments, enjoyed those special moments when a group of students who also came from Northern California visited her dorm, which was lonely for most of the school year. This sentence is very confusing for the reader. The writer seems to have added information as it came to mind. To correct excessive subordination, note the following: LaTosha Robinson, a San Francisco-native, lived in the University Park Apartments. Because her dorm was lonely most of the school year, she enjoyed those special moments when a group of students who also were from Northern California would visit. One dependent clause, who was a San Francisco-native, has been changed to an appositive. A second dependent clause, who lived in the University Park Apartments, is now the predicate of the first sentence. These changes make the sentence more direct. The subordinator of the third dependent clause has been changed from which (identification) to because (cause) to show clearly the connection between the loneliness of the dormitory and LaTosha's enjoyment of those special visits. lack of parallelism Parallel Form Most of the descriptions and examples in this section are taken from William Strunk's venerable Elements of Style, which is maintained online by the Bartleby Project at Columbia University: This principle, that of parallel construction, requires that expressions of similar content and function should be outwardly similar. The likeness of form enables the reader to recognize more readily the likeness of content and function. Familiar instances from the Bible are the Ten Commandments, the Beatitudes, and the petitions of the Lord's Prayer. Students should also visit the section on Sentence Variety, which has material on the repetition of phrases and structures. Click HERE to visit a page containing the biblical passages mentioned above. Also in this Guide is a definition of the idea of a college, a lovely example of parallel form. Students are also familiar with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, which abounds with examples of parallel form. Clicking on the title above will allow you to read this famous speech and view a brief "slide-show" demonstration of the parallel structures within Lincoln's famous text. (The Library of Congress maintains a site at which you can inspect two different drafts of the Gettysburg Address in Lincoln's own handwriting.) Unskillful writers often violate this principle, from a mistaken belief that they should constantly vary the form of their expressions. It is true that in repeating a statement in order to emphasize it writers may have need to vary its form. But apart from this, writers should follow carefully the principle of parallel construction. Faulty Parallelism Corrected Version Formerly, science was taught by the textbook method, while now the laboratory method is employed. Formerly, science was taught by the textbook method; now it is taught by the laboratory method. The left-hand version gives the impression that the writer is undecided or timid; he seems unable or afraid to choose one form of expression and hold to it. The right-hand version shows that the writer has at least made his choice and abided by it. By this principle, an article or a preposition applying to all the members of a series must either be used only before the first term or else be repeated before each term. Faulty Parallelism Corrected Version The French, the Italians, Spanish, and Portuguese The French, the Italians, the Spanish, and the Portuguese In spring, summer, or in winter In spring, summer, or winter (In spring, in summer, or in winter) Correlative expressions (both, and; not, but; not only, but also; either, or; first, second, third; and the like) should be followed by the same grammatical construction. Many violations of this rule can be corrected by rearranging the sentence. Faulty Parallelism Corrected Version It was both a long ceremony and The ceremony was both long very tedious. and tedious. A time not for words, but action A time not for words, but for action Either you must grant his request You must either grant his or incur his ill will. request or incur his ill will. My objections are, first, the My objections are, first, that the injustice of the measure; second, measure is unjust; second, that it that it is unconstitutional. is unconstitutional. When making comparisons, the things you compare should be couched in parallel structures whenever that is possible and appropriate. Faulty Parallelism Corrected Version My income is smaller than my wife. My income is smaller than my wife's. Sentence Boundaries: ability to recognize correct sentences in written English, avoiding errors in sentence boundaries such as comma splices and run-on sentences. comma splices and run-on sentences Run-on Sentences, Comma Splices A RUN-ON SENTENCE (sometimes called a "fused sentence") has at least two parts, either one of which can stand by itself (in other words, two independent clauses), but the two parts have been smooshed together instead of being properly connected. Review, also, the section which describes Things That Can Happen Between Two Independent Clauses. It is important to realize that the length of a sentence really has nothing to do with whether a sentence is a run-on or not; being a run-on is a structural flaw that can plague even a very short sentence: The sun is high, put on some sunblock. An extremely long sentence, on the other hand, might be a "run-off-at-the-mouth" sentence, but it can be otherwise sound, structurally. Click here to see a 239-word sentence that is a perfectly fine sentence (structurally) When two independent clauses are connected by only a comma, they constitute a run-on sentence that is called a comma-splice. The example just above (about the sunscreen) is a comma-splice. When you use a comma to connect two independent clauses, it must be accompanied by a little conjunction (and, but, for, nor, yet, or, so). The sun is high, so put on some sunscreen. Run-on sentences happen typically under the following circumstances*: a. When an independent clause gives an order or directive based on what was said in the prior independent clause: This next chapter has a lot of difficult information in it, you should start studying right away. (We could put a period where that comma is and start a new sentence. A semicolon might also work there.) b. When two independent clauses are connected by a transitional expression (conjunctive adverb) such as however, moreover, nevertheless. Mr. Nguyen has sent his four children to ivy-league colleges, however, he has sacrificed his health working day and night in that dusty bakery. (Again, where that first comma appears, we could have used either a period — and started a new sentence — or a semicolon.) c. When the second of two independent clauses contains a pronoun that connects it to the first independent clause. This computer doesn't make sense to me, it came without a manual. (Although these two clauses are quite brief, and the ideas are closely related, this is a runon sentence. We need a period where that comma now stands.) Most of those computers in the Learning Assistance Center are broken already, this proves my point about American computer manufacturers. Again, two nicely related clauses, incorrectly connected — a run-on. Use a period to cure this sentence. Online Resource: http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/index.htm Interactive Quizzes: http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/quiz_list.htm