printable version

advertisement

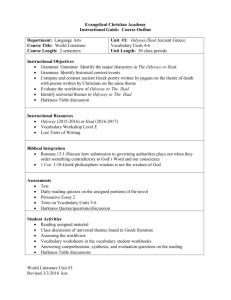

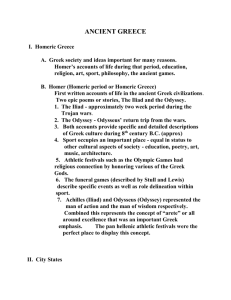

Homer The Greeks traditionally assumed that a single poet named Homer composed both the Iliad and the Odyssey, but we have no certain information about who composed these poems or how. Both the Homeric poems were composed in an oral poetic tradition that preceded the advent of writing. The Homeric poems were by far the most revered and influential works of literature in the ancient Greek (and Roman) world. They affected not only literature, both prose and poetry, but established a vision of the Heroic age that helped shape Greek society itself. Composition of Homer's Iliad c. 750-725. Composition of Homer's Odyssey c. 743-713. Identity of “Homer” and Greek Oral Poetry Greeks of the archaic and classical periods looked upon Homer as their greatest, as well one of their earliest poets, and various stories grew up about his life. Ancient sources do not agree on when Homer lived or where he came from. Ancient tradition generally connected him with Ionia, in particular with Chios and Smyrna, and the linguistic evidence of the Iliad and the Odyssey would support this, but nothing is certain. Different poets could have composed the Iliad and the Odyssey. And in the case of these epics, we cannot even define precisely what we mean by composition: the Homeric epics were composed in an oral poetic tradition that developed without the use of writing, but writing (which ultimately put an end to the oral composition of Greek poetry) has preserved for us these two poems. Did a “Homer” write these poems with his own hands? Did he dictate them to one or more scribes? Did he teach them, word for word, to disciples who then memorized and in turn passed them on to other generations of poets until they could be written down at some later date? Many have expressed opinions on these matters, but we have no hard evidence as to how these poems were composed, and we can only base our own conjectures on the rumors preserved from antiquity and from what we know of other oral traditions that have been observed in the modern world. The nature of Homeric epic itself is responsible for our ignorance of who composed these poems. The Iliad and the Odyssey are products of an oral poetic tradition, which developed without the use of writing. These poems are composed of metrical formulas: if the poet wishes to describe the sunrise in a single line, he has a ready made set of words at his disposal which he can apply. It does not matter if the same formulaic expression is repeated dozens of times in the course of a poem: the same line, for example, describes one person speaking to another (“he addressed him speaking winged words”, kai min phônêsas epea pteroenta prosêuda) at Hom. Il. 1.201, Hom. Il. 2.7, Hom. Il.4.312, Hom. Il.4.369 and at twenty-six other places in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The aesthetics of Homeric epic, at least on the level of the individual phrase or line, thus differ markedly from the conventions of modern poetry, which assiduously avoids repetition and places a very high value on novel turns of phrase. No one ever taught Greek epic poets not to repeat the same word in a single paragraph. This complex formulaic system had a functional advantage. In essence, the poet was fluent in a specialized language, in which meter was another linguistic constraint like morphology or syntax. The poet had to express all of his ideas in separate, complete lines six metrical units in length (a meter called “dactylic hexameter”). These hexameters had a fixed, precise metrical form, and were divided into separate sections of predictable length, and the epic poet learned how to assemble these formulas into the framework offered by the dactylic hexameter. The poet in effect learned a special dialect in which metrical rules were added to the normal linguistic rules of morphology and syntax. The consequence of this practice was a penchant for formulaic economy: Homeric poetry tends to use the same formula in the same segment of a line wherever possible. Thus, the Iliad refers to Diomedes as “Diomedes, good at the war cry” twenty one times in the Iliad, not because Diomedes’ vocal powers were particularly relevant to the passage at hand but because the formula boên agathos Diomêdês slipped neatly into the final segment of the line. Some events could be treated formulaically, and thus sequences of entire lines describing some conventional activity, like a sacrifice followed by a feast, might reappear at several points. Other standard organizational patterns (e.g., how do two heroes engage in a duel? how does one describe a trip to the underworld?) helped the poet organize these smaller formulas into a larger whole. This elaborate formulaic system did not just allow poets to compose hexameters quickly. It rendered singers fluent in a special poetic language, wherein all statements fitted neatly within the metrical frame of a hexameter. The Greek formulaic system of the Homeric poems allowed singers to compose hexameters extemporaneously and gave them analytical tools whereby they could modify their poems in the course of a performance. If the audience was beginning to drowse, the poet could skip quickly through a feast scene and get to a fight, or he might particularly emphasize part of a song which centered around a local hero. The poet could lengthen, shorten, modify, or, if need be, create a new song according to conventional patterns. The formulaic system made it easy for the poet to tailor his song to the interests of the audience that watched him with greater or lesser attention. It was an extraordinarily flexible tool. The flexibility of formulaic composition, however, had a powerful side effect on poetic form. The Homeric epics ultimately were memorized as precisely as any religious text, but Greek formulaic epic, when still a living phenomenon, assumed that each singer would learn the outlines of a song, not a word-for-word version. A good poet would create his own distinct version of a song and would probably modify over time, adding his own embellishments and emphasis. The system of oral composition assumed that a song had no particular existence separate from any one performance. If poems existed only in performance and had no fixed form, there was no particular reason to preserve the personality of any one poet. Of course, some poets undoubtedly earned greater reputations during their lifetimes, and they undoubtedly exploited this prestige as far as possible, but their prestige was tied to their physical ability to recreate, in performance, their songs. In the oral tradition, once a poet had passed from the scene forever, his songs were naturally gone with him. There was little cause, other than sentiment, to recall the particulars of his life and career. Within a generation or so after writing began to record poetry, the personal history and identity of poets began to emerge. Hesiod, for example, who composed non-epic hexametrical poetry and whose poetry dates somewhat later than the Iliad and the Odyssey, specifically includes his name and several details of his life in his poetry. Other types of poetry besides epic also flourished in Greece from time immemorial. The first “lyric poet” (i.e., someone who wrote songs that were to be sung accompanied by music of the lyre) whose work survives to us, Archilochus of Paros, became a celebrity in ancient times: his poetry fascinated his audience both because of its quality and because of what it revealed (or purported to reveal) about his personal life. But whoever composed the Iliad and the Odyssey came at the beginning of a tremendous shift from the oral culture to one based on writing. As already noted, we cannot even be sure whether the Iliad and the Odyssey by one poet or by two. Two of the most successful pieces of literature ever composed are, for all practical purposes, anonymous. Composition of the Iliad and Odyssey We have no solid evidence by which to date the Iliad and the Odyssey. The best current estimate, based on analysis of linguistic features of the poems ([Janko, 1982] 228-231) have concluded that the Iliad was composed between 750 and 725 and the Odyssey between 743 and 713, but the grounds for this assumption do not allow for any great certainty. Even the idea of “composition” is problematic. Oral poets had been at work in Greece continuously since the Bronze Age, and at least four centuries separated the composition of the Iliad and the Odyssey from whatever historical events may ultimately lie behind the story of the Trojan War. Our epic preserves some memory of things centuries old: it includes descriptions of several objects which had not existed since the Bronze Age: the tower shield of Ajax (Hom. Il. 7.219), the boar's tusk helmet (Hom. Il. 10.261-265) and the cup of Nestor (Hom. Il. 11.632-5). But generations of singers had each developed their own versions of these tales, and we cannot point to a single episode or even line of poetry in either the Iliad or the Odyssey which we can say was composed for the poems as we have them. Everything in both of these vast poems was “traditional,” in that any single line could be seen as a formula. Even if a particular line or phrase reappears nowhere else in the Iliad and Odyssey, we cannot be sure that this turn of phrase had not existed for generations. The most convincing discussion of the problem ([Morris, 1986]) argues that the Homeric poems may preserve isolated elements that are very old, but that it presents us with an aristocratic, idealized view of the 8th century BC. The poems, in this perspective, are less an analysis of the past than an ideological attempt to justify the values of a threatened dominant class. While the aristocrats of the eighth century lost much of their influence, the values of the Homeric poems came to exert a wide appeal in Greek society and became a common object which Greeks from throughout the scattered Greek world shared. However many poets roamed the valleys and islands of Greece, the Iliad and the Odyssey seem both of them to have been wholly different from anything else that survived. What little we know of non-Homeric epic suggests that the Iliad and the Odyssey, though constructed out of the same materials as other poems, nevertheless constituted achievements which had no parallel and which exerted a tremendous hold on the Greek imagination. Aristotle praised the Iliad and the Odyssey in comparison to non-Homeric epic (Aristot. Poet. 1459a20-1459b16), and the surviving fragments of these works suggest that they were less tightly organized, relied more on fantastic effects and were generally flatter in tone than the Iliad and the Odyssey. Importance and Influence of the Homeric Poems The great scholars who developed the Library at Alexandria from the third through the second century B.C. laid the systematic groundwork for the texts of the Iliad and the Odyssey that we use today, but roughly the same amount of time which separated Iliad from the period which it describes separated the composition of our Iliad from the founding of the Library at Alexandria. In the meantime, the Homeric poems were already major works of literature in the classical period and they exerted an enormous impact on Greek thought throughout the archaic and classical periods. From the moment the Homeric epics appear in recorded Greek tradition, they occupy a place apart from other literature. Other Greek authors view them as classics and they provide the foundation on which Greeks developed their canon of literary texts. Regardless of when the poems were actually written down, most people in the classical period encountered Homeric poetry in performance. The text of a poem should be compared with a modern score of music or perhaps the script of a play, rather than with a novel or poem designed from the start to be read. Professional singers, called rhapsodes, specialized in performing these poems, and one of Plato's dialogues (Plat. Ion), depicts a rhapsode describing his craft. Herodotus describes these singers at work in Sikyon during the rule of the tyrant Kleisthenes, in the early sixth century (Hdt. 5.67.1). According to a dialogue attributed to Plato (Plat. Hipparch. 228b), Hipparchos, son of the tyrant Peisistratos, first formally introduced Homeric poetry into Athens and instituted the custom, which still prevailed when this dialogue was composed, of having a series of rhapsodes recite the “epic poetry” of Homer from start to finish. At the same time, however, individual Greeks who were not professional singers also studied the poems of Homer intensively and were expected to know substantial portions of the Iliad and Odyssey by heart. Quotations from Homer are, for example, scattered throughout the dialogues of Plato, and we can see that well-educated Greeks (or at least the members of Athenian society who composed much of our surviving literature) would casually allude to Homer on any and all occasions. Knowledge of Homeric poetry was something which Greeks shared and which helped define what it meant to be Greek. Herodotus, in a much-discussed passage (Hdt. 2.53), claims that the poetry of Homer and Hesiod largely defined for the Greeks who their gods were and what roles the gods filled. Some papyrus fragments preserved in the dry climate of Egypt do survive which shed light upon the text of the Homeric poems before Alexandrian scholarship went to work collecting and freezing a single, definitive version of the poems. In these so-called “wild papyri” there are many extra lines and noticeable additions, but for the most part they do not in fact differ substantively from the texts that we now read. Our texts of the Iliad and the Odyssey have faithfully preserved many dialectical and linguistic peculiarities which had vanished from the Greek language for centuries. Both in overall content and in wording our texts seem to provide a fairly good picture of what an audience might have heard in a performance of the eighth century. For traditions of Homer's life, see [Lefkowitz, 1981] 12-24.> For brief introductions to Homer, see [Easterling, 1985] 42-52, 721-724; [Kirk, 1985] 1-16. For the dating of Homer, see [Janko, 1982] 228-31. A group of scholars has recently translated into English Friedrich August Wolf's 1795 book, Prolegomena to Homer, which framed the “Homeric Question,” i.e., did a single poet compose the Iliad and the Odyssey ([Wolf, 1985]). On Homer and Oral Poetry, [Lord, 1960] 141-197, and [Parry, 1971] remain the starting point. [Morris, 1986] argues that the Homeric poems reflect the world of the eighth centuries, and on this he updates, but does not replace, [Finley, 1954]. Atchity, Kenneth, Ron Hogart, and Don Price, ed. Critical Essays on Homer. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987. viii+245. Bloom, Harold, ed. Homer's Odyssey: Edited and with and Introduction. New York: Chelsea House, 1988. vii+167. Bloom, Harold, ed. Homer's The Iliad: Edited and with an introduction. New York: Chelsea House, 1987. vii+160. Crane, Gregory. Calypso: Backgrounds and Conventions of the Odyssey. Athenaums Monografien: Altertumswissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum, 1988. 191: 190. Edwards, Mark W. Homer: Poet of the Iliad. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987. x+341. Griffin, Jasper. Homer: The Odyssey. Landmarks of World Literature. Cambridge: Cambrige University Press, 1987. vi+107. Janko, Richard. Homer, Hesiod and the Hymns: Diachronic Development in Epic Diction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. xvi+322. Kirk, G. S. The Iliad: A Commentary: Books 1-4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. 1: Martin, Richard P. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Myth and Poetics. Ed. Gregory Nagy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989. xv+265. Murnaghan, Sheila. Disguise and Recognition in the Odyssey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987. ix+197. Nagler, Michael N. Spontaneity and Tradition : a Study in the Oral Art of Homer. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974. xxv+236. Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979. xvi+392. Nagy, Gregory. Pindar's Homer: the Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990. 523. Parry, Adam, ed. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971. Peradotto, John. Man in the Middle Voice: Name and Narration in the Odyssey. Martin Classical Lectures. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. 193. Scully, Stephen. Homer and the Sacred City. Myth and Poetics. Ed. Gregory Nagy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990. xi+230. Silk, M. S. Homer: the Iliad. Landmarks of World Literature. Cambrige: Cambrige University Press, 1987. vii+116. Tracy, Stephen V. The Story of the Odyssey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. xiv+160. Whitman, Cedric H. Homer and the Heroic Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958. xii+365. Willcock, Malcolm M. A Commentary on Homer's Iliad. London: Macmillan, 1970. xxviii+228.