K $ñT - Canadian Association for Spiritual Care

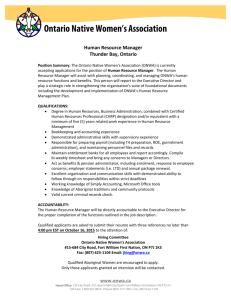

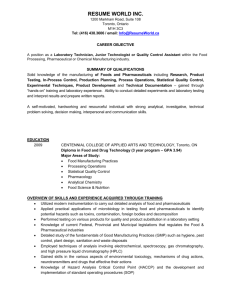

advertisement